To Kiss a Thief (28 page)

Authors: Susanna Craig

Historical Note

From the late seventeenth century until the early nineteenth, Great Britain's most valuable colonial possessions were a few small islands in the Caribbean Seaâplaces like Barbados, Jamaica, and Antiguaâwhere sugarcane could be grown. In what would come to be known as the Triangular Trade, money and goods from Britain were used to purchase African slaves and ship them to plantations in the West Indies; the sugar produced by slave labor was sold at great profit in Britain, enabling the cycle to continue. Sugarcane's almost year-round growing season and intensive harvest demands, combined with the disease-ridden tropical environment, made sugar production especially brutal work. To maximize profits, slaves were given little in the way of clothing, food, or rest, and overseers enacted horrific punishments to extract labor and to quash resistance.

In the Runaway Desires series, characters confront this ugly reality, come to terms with their roles in it, and challenge it when they can. In this, as in so many ways, the heroes and heroines of romance are unfortunately far from typical. Most eighteenth-century Britons, far removed from the West Indies, were indifferent to slavery. Others regarded it as a positive good, both in economic terms and as a means of “civilizing” Africans, views reinforced by propaganda from the powerful West India Lobby, made up of planters, merchants, bankers, and Members of Parliament. An anti-slavery movement did not emerge until the closing decades of the century, when the tide slowly began to turn. In 1772, Chief Justice Lord Mansfield issued a ruling challenging the legality of slavery, widely interpreted to mean that any slave brought to Britain from the colonies was free on English soil. Following fierce debate in the 1790s, the slave trade was outlawed in the British Empire in 1807, and slavery itself was formally abolished in the British colonies in 1833, though many of the harsh conditions and attitudes persisted long after.

Keep reading for a sneak preview of

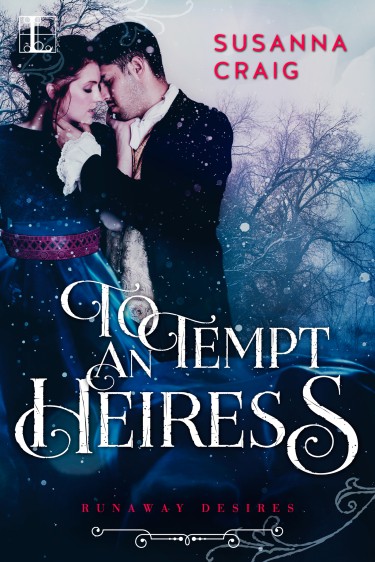

TO TEMPT AN HEIRESS

The next in Susanna Craig's

Runaway Desires series

Click here to get your copy.TO TEMPT AN HEIRESS

The next in Susanna Craig's

Runaway Desires series

Chapter 1

Near English Harbour, Antigua

October 1796

October 1796

Â

C

aptain Andrew Corrvan would never claim to have acted always on the right side of the law, but there were crimes even he would not stoop to commit.

aptain Andrew Corrvan would never claim to have acted always on the right side of the law, but there were crimes even he would not stoop to commit.

Kidnapping was one of them.

This conversation ought to have been taking place in some dark, dockside alley, not in the sun-dappled sitting room of the little stone house occupied by the plantation manager at Harper's Hill. Andrew had never met the man before today, although he knew him by reputation. Throughout Antigua, Edward Cary was talked of by those who knew him, and by many more who didn't, as a fool. As best Andrew had been able to work out, he had earned the epithet for being sober, honest, and humane, a string of adjectives rarely, if ever, applied to overseers on West Indian sugar plantations.

As the afternoon's exchange suggested, however, even a paragon of virtue could be corrupted by a villainous place. Why else would Cary be attempting to arrange the abduction of a wealthy young woman?

“So, the talk of valuable cargo was just a ruse to lure me here?” Andrew asked.

“Not at all,” Cary insisted with a shake of his head. “Between her father's private fortune, which she has already inherited, and Harper's Hill”âhe swept his arm in a gesture that took in the plantation around themâ“which she will inherit on her grandfather's death, Miss Holderin is worth in excess of one hundred thousand pounds.”

Despite himself, Andrew let a low whistle escape between his teeth. The chit would be valuable cargo indeed. “And how do you benefit from sending her four thousand miles away?”

“I don't,” Cary said, and behind that rough-voiced admission, and the mournful expression that accompanied it, lay a wealth of meaning. So the man had taken a fancy to his employer's granddaughter, had he? The more fool, he. “When Thomas Holderin was on his deathbed I gave him my solemn oath I would do all in my power to look after his daughter.”

“And now you wish to be rid of the obligation.”

“I

wish

â” he began heatedly. But apparently deciding his own wishes were beside the point, he changed course and said instead, “I believe she will be safer in England.”

wish

â” he began heatedly. But apparently deciding his own wishes were beside the point, he changed course and said instead, “I believe she will be safer in England.”

“Then book her passage on the next packet to London.” Andrew thumped his battered tricorn against his palm, preparatory to placing it on his head and taking his leave. At his feet, his shaggy gray mongrel, Cal, rose and gave an eager wag of his tail, bored with all the talk and ready to be on his way.

“If I could, I would. I have tried many times to reason with her. But Miss Holderin is . . . reluctant to leave Antigua. She believes she is more than a match for the dangers the island presents.” Cary turned toward the window. “She is wrong.”

Andrew followed the other man's gaze. Fertile fields, lush forest, and just a glimpse of the turquoise waters of the Caribbean Sea where they touched a cerulean sky. It would have been difficult to imagine a less threatening landscape, but Andrew knew well that appearances could deceive. The dangers here were legion.

“Why me?” Andrew asked after a moment, folding his arms across his chest and fixing the other man with a hard stare. “Do you know the sort of man I am?”

Unexpectedly, Cary met Andrew's gaze with an adamant one of his own. “I do. You are said to be a ruthless, money-hungry blackguard.”

Andrew tipped his chin in satisfied agreement. He had spent ten years cultivating that reputation.

“But of course, the sort of man you are

said

to be might not be entirely accurate, I suppose,” Cary continued, steepling his fingers and tilting his head to the side. “Your crew tells a slightly different story, Captain.”

said

to be might not be entirely accurate, I suppose,” Cary continued, steepling his fingers and tilting his head to the side. “Your crew tells a slightly different story, Captain.”

Despite himself, Andrew shifted slightly. The movement might have gone unobserved if not for the dog, whose ears pricked up, as if awaiting some command.

One corner of Cary's mouth curled upward as he glanced at Cal. “Most of the sailors on your ship were admirably tight-lipped, rest assured,” he said. “But then I happened to make the acquaintance of a fellow called Madcombe. New to your crew, I believe.”

Andrew jerked his chin in affirmation. There was no denying Timmy Madcombe was a talker. He might have told Cary anything, and probably had.

“He seemed most grateful to find himself aboard a ship captained by what he called a âr'al gent,' you will be pleased to know. âGood grub, a fair share, an' no lashin's, neither,' ” Cary added, mimicking Timmy's voiceâright down to the occasional crack that gave the lie to the lad's claim of being fourteen. “If that proves true, such a style of shipboard management would make you rather unusual among your set.” This time, Andrew was careful not to move, offering neither acknowledgment nor denial. Still, Cary seemed to read something in him. “Yes”âhe nodded knowinglyâ“Madcombe's story, and the vehemence with which the rest of your crew attempted to keep him from telling it, made me wonder if you are quite as ruthless as you wish to seem.”

“If you are willing to take the word of that green boy, you must be desperate, indeed,” Andrew said, pushing back against Cary's probing.

“I am.” Cary flicked his gaze up and down, taking in every detail of Andrew's appearance. “Desperate enough to hope that in some ways at least, you are as ruthless as you lookâdespite any assurances I may have received to the contrary. For it will take a ruthless man to succeed.”

“I take it Miss Holderin's is not the only resistance I can expect to encounter if I take her away.”

“Hers will be formidable,” Cary warned. “Do not underestimate it. You may be required to use some rather creative measures to get her aboard your ship.”

Creative measures?

A sudden sweat prickled along Andrew's spine. Nothing about this situation sat well with him.

A sudden sweat prickled along Andrew's spine. Nothing about this situation sat well with him.

A welcome breath of wind stirred the draperies behind him, drawing cooler, sweetly scented air through the house, scattering some papers across the desk beside which Cary stood. “But I will confess, her opposition is not my primary concern,” he continued. “As you might imagine, an heiress of Miss Holderin's magnitude receives a great deal of attentionâunwelcome attentionâfrom prospective suitors. And one of them is not content to accept her refusal.”

“If she's turned the man down, what of it?” Andrew dismissed the supposed menace with a shrug. “He can't bloody well drag her down the aisle, bound and gagged.”

“Can he not?” Cary asked. Absently, he neatened the stack of papers disordered by the breeze, weighting them with a green baize ledger, never raising his eyes from the desk. “I wish I shared your certainty about the matter. But we live on the very edge of what might be considered civilized society, Captain, and Lord Nathaniel Delamere has lived the sort of life that has put a great many influential men in his thrall. Men who would be willing to look the other way if some injustice were done. Planters. Merchants.” At last he lifted his gaze. “Even a clergyman or two.”

“There's something rather odd about your determination to go against Miss Holderin's express wishes in order to keep another man from doing the same,” Andrew pointed out.

By the expression on Cary's face, Andrew guessed the irony had not been lost on him. “If she learns what I've done, she will never forgive the betrayalâI know that. But Delamere will stop at nothing to get his hands on Harper's Hill and Thomas Holderin's fortune. And once he has what he wants, what will become of her? She will not listen to reason. What ought I to do?”

The question hung on the air between them for a long moment.

“A desperate man. A dangerous voyage. And an heiress who doesn't want either one.” Andrew ticked off each item on his fingertips. Perhaps it was her plantation manager from whom Miss Holderin most needed to be saved. “I thank you for the consideration, but I think I'll pass. Find another ship to do your dirty work, Cary.”

“Would you have me trust her with just anyone? I have reason to believe you're a man of honor. Besides,” he added frankly, “yours is the last private vessel in the harbor over which Delamere has no hold. You are my best hope, Captain Corrvan.”

But Andrew had learned long ago not to be swayed by another's tale of woe. “London is not on the

Fair Colleen

's route,” he said, moving toward the door and motioning the dog to follow.

Fair Colleen

's route,” he said, moving toward the door and motioning the dog to follow.

Before he could take more than a step or two, there was a knock at the door. “Put down that musty old ledger, Edward,” a feminine voice rang out in the corridor. “Angel's Cove is beckoning. I can ask Mari to pack us aâoh!”

Startled by the intrusion, Cal charged toward the door, barking furiously. The woman dropped the book she had been carrying and let out an inhuman screech of alarm. Suddenly, the once-quiet sitting room was a flurry of activity: a flash of brown hair, more shrieks, and two snarling leaps into the air.

“Cal!” Andrew grasped the dog's collar.

Stepping past him, Cary shouted, “Stop that racket, you little devil.”

More defiant screeches, another brown blur, and Andrew at last sorted out the source of both the noise and the confusion: a little monkey, who had been driven up the wall by Cal's unexpected greeting and now clung to the curtain rod, taunting the dog. Cal strained against his collar, trying to lunge at the unfamiliar animal, and Cary's brow was knit in a fierce frown.

On the floor sat the woman, perhaps two- or three-and-twenty, her heart-shaped face framed by red-gold curls that tumbled down her back in inviting disarray, barely contained by her broad-brimmed straw hat. She was emphatically

not

screeching. That had been the monkey.

not

screeching. That had been the monkey.

No, the woman was laughing.

Once she had recovered her breath, she scrambled to her feet without waiting for an offer of assistance from either man and instead held out her hand to the monkey. “Come, Jasper. Mind your manners.”

When Jasper refused with a mocking grin and a vigorous shake of his head, the woman shrugged and turned toward Andrew. “My apologies. He doesn't respond well to being startled. But you couldn't know that, could you?” she said in a hearty voice, ruffling the dog's shaggy gray ears once her hand had been sniffed and approved. “What a brave boy . . . Cal, did you call him?”

Then her fingers met Andrew's in the dog's rough fur, and with a gasp of surprise, she jerked her hand away. Had she felt it, too, the warning spark that had passed between them when they touched?

She glanced upward, and Andrew, who was still bent over the dog, found himself just inches from the most startling eyes he had ever seen. A swirling mixture of blue and green and gray for which there was no name.

He straightened abruptly and tugged the dog a respectable distance away. “Caliban, actually.”

“Caliban?” she echoed, wiping her hands down the skirt of her brownish-green dress, which was already smudged with dusty handprints.

“After the half-man, half-beast inâ”

“In

The Tempest

,” she finished. Something that was not quite a smile lurked about her lips, and her blue-green eyes twinkled. “By Mr. Shakespeare.”

The Tempest

,” she finished. Something that was not quite a smile lurked about her lips, and her blue-green eyes twinkled. “By Mr. Shakespeare.”

“It seemed a fitting name for such a mongrel,” Andrew said with a glance at the dog's feathery tail where it thumped against the floorboards. Since when was Cal's affection to be won with a pat on the head?

When he turned back to face the woman, he found his own appearance an object of similar scrutiny. “And you are?” she asked.

“Captain Andrew Corrvan.” Cary inserted himself between them and completed the introductions. “Miss Tempest Holderin.”

“Tempest?” Unable to keep the note of disbelief from creeping into his voice, Andrew still managed a bow. Although he had cast aside most other hallmarks of a gentleman's upbringing, too many years of training had made that particular gesture automatic.

Cary's explanation was predictably measured. “Her father was . . . unconventional.”

“A lover of Shakespeare,” Tempest Holderin corrected. Her eyes flashed, and at once he realized why their unusual hue looked so hauntingly familiar to him. They were eyes in which a man might easily drown, the precise shade of the sea before a storm.

Perhaps Thomas Holderin had known what he was about, after all.

“The two are hardly mutually exclusive,” Andrew remarked, a part of him hoping she would rise to the challenge in his words. “No matter how much your father might have enjoyed the Bard, you cannot deny that the more conventional choice would have been for him to choose the name of a character from one of Shakespeare's plays, rather than naming you after the play itself.”

“Perhaps he felt Caliban wouldn't suit,” she shot back, lifting her pointed chin.

Andrew fought the temptation to smile. “I was referring, of course, to Miranda.”

His familiarity with the play seemed to surprise her. “âO brave new world, that has such people in 't!' ” She quoted Miranda's famous line, the moment at which the sheltered heroine of

The Tempest

glimpses a handsome young man. But she spoke it with the sort of half sigh more befitting the character's world-weary father, Prospero. “No, Miranda would never have done. I assure you I am not so naïve as she. Particularly where men are concerned,” she added, not quite under her breath.

The Tempest

glimpses a handsome young man. But she spoke it with the sort of half sigh more befitting the character's world-weary father, Prospero. “No, Miranda would never have done. I assure you I am not so naïve as she. Particularly where men are concerned,” she added, not quite under her breath.

“If you'll excuse us, Tempest.” Cary seemed to find little amusement in the exchange. “Captain Corrvan and I have a matter of urgent business to discuss.”

“Business? Excellent,” she declared, standing firm. “I've been meaning to ask you about Dr. Murray's report on Regis's leg. And have you heard from Mr. Whelan? I know the harvest is almost upon us, but I won't have people put to work in the mill if there's danger of it collapsing.”

Other books

A Lycan's Mate by Chandler Dee

Bear Shifters: Hunt Collection #1 by Ava Hunt

Sacking the Quarterback by Samantha Towle

On the Hook by Cindy Davis

Alessandro's Prize by Helen Bianchin

The Husband Diet (A Romantic Comedy) by Barone, Nancy

Lost To Me by Jamie Blair

Murder, She Wrote by Jessica Fletcher

Blood Work by Holly Tucker

Vegan for Life by Jack Norris, Virginia Messina