Titanic (24 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

A chair sling at each gangway, for getting up sick or wounded. Boatswains’ chairs. Pilot ladders and canvas ash bags to be at each gangway, the canvas ash bags for children to help get infants and children aboard. Cargo falls with both ends clear; bowlines in the ends, and bights secured along ship’s sides, for boat ropes or to help the people up. Heaving lines distributed along the ship’s side, and gaskets handy near gangways for lashing people in chairs, etc. Ordered company’s rockets to be fired at 2:45 a.m. and every quarter of an hour after to reassure

Titanic

. As each official saw everything in readiness, he reported to me personally on the bridge that all my orders were carried out, enumerating the same, and that everything was in readiness.

Meanwhile, as he struggled desperately to fight the cold and keep his balance, Jack Thayer could feel Collapsible B sinking lower beneath him. The pocket of air under the lifeboat was escaping faster. Icy seawater splashed higher against his legs with each wave.

Even as he looked at the steamship in the distance and its promise of survival, Jack felt his hope slipping away. “We had visions of sinking before the help so near at hand could reach us.”

The men on Collapsible B could see the ship beginning to pluck survivors from other boats.

“The

Carpathia

, waiting for a little more light, was slowly coming up on the boats and was picking them up,” said Jack. “With the dawn breaking, we could see them being hoisted from the water. For us, afraid we might overturn any minute, the suspense was terrible.”

Then another welcome sight met their eyes. “. . . on our starboard side, much to our surprise . . . were four of the

Titanic

’s lifeboats strung together in line,” said Colonel Gracie.

Lightoller had an officer’s whistle in his pocket. He put it to his cold lips and blew a shrill blast.

“‘Come over and take us off,’” Colonel Gracie heard him cry.

Gracie was relieved to hear the ready response: “‘Aye, Aye, sir.’”

Jack Thayer guessed it was about six-thirty in the morning when the other lifeboats drew toward them.

“It took them ages to cover the three or four hundred yards between us,” he said. “As they approached, we could see that so few men were in them that some of the oars were being pulled by women.”

One of the women in Lifeboat 4 was Jack’s own mother. Jack was so cold and miserable, he didn’t even see her.

When they made the precarious transfer into Lifeboats 4 and 12, Colonel Gracie helped Lightoller try to save one more life.

“Lightoller remained to the last, lifting a lifeless body into the boat beside me,” Colonel Gracie recalled. “I worked over the body for some time, rubbing the temples and the wrists, but when I turned the neck it was perfectly stiff. Recognizing that rigor mortis had set in, I knew the man was dead . . . Our lifeboat was so crowded that I had to rest on this dead body until we reached the

Carpathia

, where he was taken aboard and buried.”

Lightoller now took charge of Lifeboat 12, packed with about seventy-five men, women, and children. The danger was far from over.

Exhausted, cold, and in shock, the survivors in Lifeboat 12 had little idea of the peril they were in. The weight of the additional passengers from Collapsible B could sink the boat any minute.

“Sea and wind were rising,” said Lightoller. “Every wave threatened to come over the bows of our overloaded lifeboat and swamp us.”

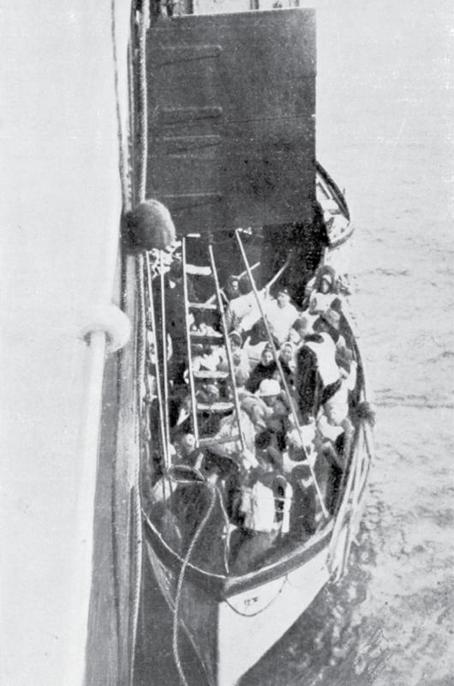

(Preceding image)

A rope ladder is being fixed from a lifeboat to the

Carpathia

so survivors may disembark.

Elizabeth Shutes, in Lifeboat 3, had been keeping watch for lights throughout that almost endless night. She could hardly believe her eyes when the

Carpathia

appeared at last.

“All night long I had heard, ‘A light!’ Each time it proved to be one of our other lifeboats, someone lighting a piece of paper, anything they could find to burn . . . Then I looked and saw a ship. A ship bright with lights; strong and steady she waited, and we were to be saved . . .

“From the

Carpathia

a rope forming a tiny swing was lowered into our lifeboat, and one by one we were drawn into safety. . . . I bumped and bumped against the side of the ship until I felt like a bag of meal,” Elizabeth remembered.

“My hands were so cold I could hardly hold onto the rope, and I was fearful of letting go . . . At last I found myself at an opening of some kind and there a kind doctor wrapped me in a warm rug and led me to the dining room, where warm stimulants were given us immediately and everything possible was done for us all.

“Lifeboats kept coming in, and heart-rending was the sight as widow after widow was brought aboard. Each hoped some lifeboat ahead of hers might have brought her husband safely to this waiting vessel . . .”

“It seemed to me an interminable time before we reached the

Carpathia

,” said Colonel Gracie, now packed into Lifeboat 12 with Second Officer Lightoller in charge.

Lightoller felt the same way. But then, at long last, the

Carpathia

was only a hundred yards away. “Now to get her safely alongside! We couldn’t last many minutes longer, and round the

Carpathia

’s bows was a scurry of wind and waves that looked like defeating my efforts after all. . . .”

Lightoller had been in a constant state of action since he had begun to uncover the lifeboats the night before. He must have been exhausted and cold. But somehow, through his skillful maneuvering, he was able to bring the overloaded lifeboat into the calm water by the

Carpathia

’s bow.

Bosun’s chairs were lowered for those unable to climb up the rope ladder. Colonel Gracie, despite his ordeal, was able to move under his own steam.

“All along the side of the

Carpathia

were strung rope ladders. There were no persons about me needing my assistance, so I mounted the ladder, and, for the purpose of testing my strength, I ran up as fast as I could and experienced no difficulty or feeling of exhaustion,” Gracie wrote later. “I entered the first hatchway I came to and felt like falling down on my knees and kissing the deck in gratitude for the preservation of my life.”

Once on board, Colonel Gracie made his way to the dining salon, where he found that the women passengers on the

Carpathia

were eager to help the survivors get warm and dry.

“All my wet clothing, overcoat and shoes, were sent down to the bake-oven to be dried,” he recalled. “Being thus in lack of clothing, I lay down on the lounge in the dining saloon corner to the right of the entrance under rugs and blankets, waiting for a complete outfit of dry clothing.”

When he thought about all that had happened to him, Colonel Gracie was sure that keeping his cool had been the reason he was still alive. “I was all the time on the lookout for the next danger that was to be overcome. I kept my presence of mind and courage throughout it all. Had I lost either for one moment, I never could have escaped to tell the tale.”

Gracie also knew how lucky he was — luckier than so many others, including his friend James Clinch Smith. Gracie could easily have been knocked senseless by debris during those chaotic minutes in the water. As it was, he’d taken more of a beating than he realized: He had a bump on his head, cuts on both legs, and bruises on his legs and knees. “I was sore to the touch all over my body for several days.”

Like Colonel Gracie, Jack Thayer was able to climb up the ladder onto the

Carpathia

on his own. “It was now about 7:30 a.m. We were the last boat to be gathered in. The only signs of ice were four small, very scattered bergs, ’way off in the distance.

“As I reached the top of the ladder, I suddenly saw my Mother. When she saw me, she thought, of course, that my Father must be with me. She was overjoyed to see me, but it was a terrible shock to hear that I had not seen Father since he had said good-bye to her.”

Not long after, someone handed him a cup of brandy. “It was the first drink of an alcoholic beverage I had ever had. It warmed me as though I had put hot coals in my stomach, and did more too,” said Jack.

“A man kindly loaned me his pajamas and his bunk, then my wet clothes were taken to be dried, and with the help of the brandy I went to sleep till almost noon,” said Jack. “I got up feeling fit and well, just as though nothing bad had happened.

“After putting on my own clothes, which were entirely dry, I hurried out to look for Mother. We were then passing to the south of a solid ice field, which I was told was over twenty miles long and four miles wide.”