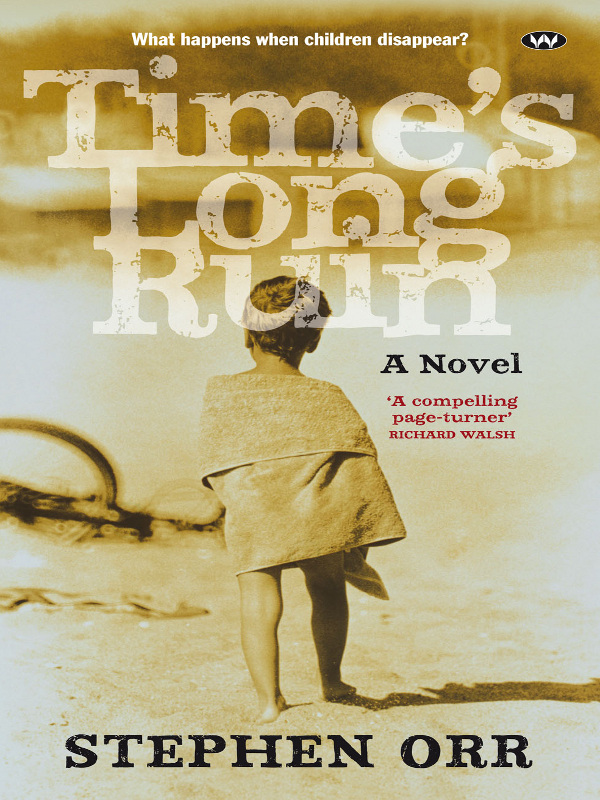

Time's Long Ruin

Wakefield Press

Time's Long Ruin

Stephen Orr's first novel,

Attempts to Draw Jesus

, described the disappearance of two jackaroos in the Great Sandy Desert in 1987. His second published work,

Hill of Grace

, was a study of delusion and disappointment in a 1950s religious cult. His short fiction has been widely published in journals and magazines. He works as a high school teacher in Adelaide.

A Novel

STEPHEN ORR

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

First published 2010

This edition published 2011

Copyright Stephen Orr, 2010

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Liz Nicholson, designBITE

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author:                   Orr, Stephen, 1967â    .

Title:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Time's long ruin/Stephen Orr.

ISBN:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 978 1 86254 974 6 (epub).

Dewey Number:Â Â Â Â Â A823.4

Contents

â â

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait

at the end to arrest it,

And ceas'd the moment life appear'd.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

â Walt Whitman

That all should change to ghost and glance and gleam,

And so transmuted stand beyond all change,

And we be poised between the unmoving dream

And the sole moving moment â this is strange.

Past all contrivance, word, or image, or sound,

Or silence, to express, that we who fall

Through time's long ruin should weave this phantom ground

And in its ghostly borders gather all.

There incorruptible the child plays still

The lover waits beside the trysting tree

The good hour spans its heaven, and the ill,

Rapt in their silent immortality.

As in commemoration of a day

That having been can never pass away.

â Edwin Muir

For never was I not, nor thou, nor these kings;

Nor will any of us cease to be hereafter.

â Bhagavad-Gita

Chapter One

The streets of Croydon are long, washed with light on long Saturday afternoons, smelling of freshly cut grass and jasmine, the air dry, venting over-ripe compost and the third race from Cheltenham. Smelling of candied almonds and Mr Hessian's chicken shit, piled in heaps in his backyard. Looking like the world had ended, or at least descended into a hibernation of half-sleep, of tea cosies to be crocheted and

Advertiser

obituaries to be re-read. Sounding of children dragging sticks along a corrugated-iron fence and someone laughing so hard they start coughing, and then someone else calling for Jack to come in for a haircut.

The streets of Croydon are wide. Hot and cracking. Starting at Thomas Street (my street) and narrowing as they head west towards the factories of Kilkenny. Streets like spines, sprung with ribs named Ellen Street and Croydon Avenue. Kept long and straighter still by power lines hanging heavily from Stobie poles like lights on an overloaded Christmas tree.

When I was five I used to think it would take an hour to walk the length of Harriet Street (although it actually takes ten minutes). I liked to think that when you got to the end you'd just drop off the edge of the world. I imagined maps, drawn in gold and red ochre inks on vellum, decorated with sailors falling into the mouths of dragons, and Mrs Brooks, the infant teacher. I knew this wasn't actually true. For one, Dad had a world globe and he'd spend hours showing me where the pyramids and the Greek islands were â and anyway, how had God crammed a whole world of beaches, car factories and New Zealand holidays into Croydon?

I've lived my whole life at number seven Thomas Street â across the road from Con and Rosa Pedavoli and their healing tree, next door to Kazz and Ron Houseman on one side and the Rileys on the other, at 7A. All of them now dead or gone, leaving me alone in the house I've lived in for fifty-four years. Walking up and down a hallway my parents carpeted with a rich red Berber, over floorboards that haven't smelt air since 1956, which creak in exactly the same spot every time I go to make a cup of tea or take a pee.

I remember our home being something special. I remember the day Dad removed the old wooden windows. Ron Wells the butcher came over to help him put in a set of brand-new aluminium ones that didn't quite fit and had to be packed with timber wedges. People stood on the footpath staring through our rampant iceberg roses.

âJesus, he'll never have to paint again,' they said, and pretty soon aluminium windows were appearing all over Croydon.

Our house was built in 1910. Twelve and a half foot ceilings and a fireplace in every room. After buying the house in 1950 the first thing my father did was to block the chimneys and put a gas heater in every fireplace. Proper job. Mr Wells helped him with the flues and gas lines, and the laying of bricks in rows that never looked straight. That's how it was done back then. No point paying someone when you could do it yourself.

We had a garden full of foxgloves and clivia, dissected with paths that were variously sawdust, gravel and weak concrete that eventually broke up. A few years ago I dug it all up and piled it in a corner of the backyard. Eventually I'll find a use for it. In time the path went muddy and weedy and then the weeds gave up and died off anyway. By then the asparagus fern and pittosporums were dead. But the aggies and clivias are still going, just. Hard bastards. That's why everyone used to plant them. Now people have got silver birches and box hedge they trim every three days with a little plug-in number from Kmart.

Like most homes in Croydon ours has four rooms and a hallway, and attached to the back wall, a kitchen and a laundry under a sloping roof. My father refused to call this a lean-to. A lean-to was something the pioneers had.

My room is at the front, looking out on Thomas Street. It's the same room and the same bed I've slept in since my mother and father brought me home from hospital in January 1951. There was never a cot â just a wall on one side and a guardrail made from salvaged window wood on the other. A single globe hangs from the high ceiling and there is a wardrobe with a door missing (which I never found or had explained). This is the room in which my mother, Ellen Judith Page, laid me, Henry, the great disappointment of her life, on a stinking hot day. As she looked at my twisted foot and sighed (perhaps), she whispered to Dad, âYou can get up to him.'

My mother had a club foot. When she married Dad she told him, as long as you never want children . . . I'd never put anyone through this. That is, her left foot, twisted inwards at an angle of thirty degrees.

Fine, my father replied, thinking he'd talk her around later.

So Dad got talking to Doctor Gunn, and our proper doctor, Doctor John, and the doctor who did the physicals for the police, and any other doctor, physio or coroner he came across in his work as a copper. And they all told him (he told me years later) that club foot couldn't be passed on. It just happened: one in a million. He explained this to Mum and the next thing you know she's pregnant. Obviously I don't know the exact details, and maybe it doesn't matter, but for years after she would always blame him for having âno idea about anything', and he'd tell her to grow up, and off they'd go with their shouting.

I have a mental picture of the delivery suite at Calvary hospital. It's hot. I can hear fan blades turning slowly and see nurses in starchy aprons wiping sweat from their foreheads. I can smell bleach, hair oil and a distant roast leg blowing in through rusted flywire speckled with blowies. I can see the child, Henry Page, lying on a towel, and the doctor's expression, and then Mum looking at him. âWhat is it?'

As the chatter of a few nurses falls silent. As Dad comes around to look at me more closely.

As Mum repeats, âWhat, what is it?'

It's not like I was born without an arm, or Mongoloid, or covered in a strawberry birthmark. It was just my foot, curving inward. What was she worried about? That the rest of my body might follow, contort, scrunch into a ball? That my mind might turn inward, losing its ability to communicate? That I might become some sort of spastic that she'd have to hide away for the rest of eternity, feeding me custard and wiping my arse as the sounds of normal children playing chasey or cricket drifted in the window?

I still don't know.

So there's me. Wrapped in a blanket despite the heat. In the arms of a nun. Being presented to my mother, who turns her head away. Who looks at my father and then stares down at the lino floor, worn thin in the same places by doctors and nurses bringing children into the world.