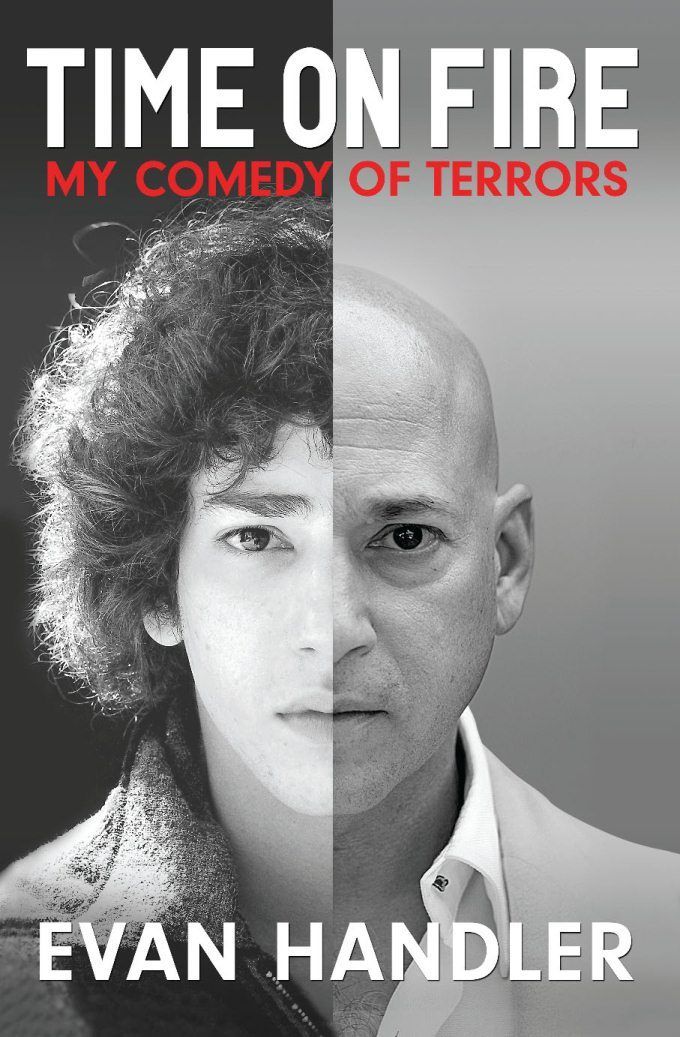

Time on Fire: My Comedy of Terrors

Read Time on Fire: My Comedy of Terrors Online

Authors: Evan Handler

My Comedy of Terrors

by

Evan Handler

Copyright © 1996, 2012 by Evan Handler

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced, downloaded, scanned, stored, or distributed in any stored in any form or manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

For information, address Oxymoronic Industries, Inc. c/o David Black Agency, 335 Adams Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the author does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for third-party websites or their content.

Throughout this book, the names of some places as well as individuals and their personal details have been changed.

Print ISBN 9780786754786

ebook ISBN 9780786754793

Cover design by Gary Dorsey/Pixel Peach Studio/Austin, TX

Author photos by Van Williams and Robert Rosenheck

Distributed by Argo Navis Author Services

It’s Only Temporary: The Good News and the Bad News of Being Alive

It’s Only Temporary

“In

It’s Only Temporary

, Evan Handler confronts the ambiguities of life backward, forward, and in between. With hilarious honesty he reflects on the realization that we can start over again…A heartfelt book for all of us who are getting younger and older at the same time.”

—Amy Tan, author of

The Joy Luck Club

,

The Bonesetter’s Daughter

,

and

The Kitchen God’s Wife

“In a series of wonderful essays, Evan Handler gives himself up to us – warts and all. To our amusement and bemusement we share in his emotional growth as he struggles to mature. I not only laughed along with him but felt that I too had grown a little along the way. Who could ask for more?”

—Lewis Black, comedian, Daily Show correspondent, and author of

Nothing’s Sacred

“Evan Handler’s new book is simply wonderful. He pulls you inside his life, and you come out his very close friend.”

—Neil Simon, Pulitzer Prize winning playwright/screenwriter of

Lost In Yonkers

,

The Odd Couple

,

Brighton Beach Memoirs

, and

The Goodbye Girl

“Evan Handler is not only a fine actor, he’s a damn good writer. It’s Only Temporary is wise and funny and as righteously indignant as it is endearingly self-effacing. In what may be a literary first, the book actually left me wanting more.”

—Meghan Daum, author of

My Misspent Youth

and

The Quality of Life Report

“Evan Handler’s unsparingly honest stories about life, love, and his own shortcomings are hilarious to read and oh, so easy (and fun!) to relate to. By the end you will be left with the surprising but unmistakable feelings of hope and redemption. It’s Only Temporary is truly an inspiration, particularly for anyone who’s out there looking for love.”

—Liz Tuccillo, co-author of

He’s Just Not That Into You

“Evan Handler is a man who’s looked into the abyss and laughed. His book,

It’s Only Temporary

, made me laugh along with him. He covers love, lust, showbiz, triumph, and despair – and he manages to be both funny and inspiring about all of it. It’s an important book that I think can help to spread goodness around the world. Something we desperately need.”

—Lance Armstrong, Founder, The Lance Armstrong Foundation

For Murry and Enid;

Lillian and Lowell

…old sorrow, written in tears and blood.

A sadly inappropriate gift, it would seem…

Eugene O’Neill, 1941

And I will never, ever, ever, ever grow so old again.

Van Morrison,

“Sweet Thing”

“I’m afraid it is not good news,” is what he said. “It is bad news. It is in the bone marrow. It’s an acute myelogenous leukemia.”

Now, for some reason this doctor, in my memory, has turned into Richard Nixon. If Richard Nixon had ever been interested in acting, in the movie, I’d have given him the part.

We were in this doctor’s office for some time after that. My parents, my girlfriend, Jackie, and me. There was some talk of intensive chemotherapy, remission rates, the phrase “not curable” hit me from somewhere. I only remember that I kept rubbing the side of my face, really hard.

“Okay, okay, okay,” I finally said, and everyone seemed a little bit startled, as if they’d forgotten I was actually there in the room with them. “I have to get out of here now. We can talk about all this later,” and I got up to go.

“I wouldn’t wait very long,” Dr. Nixon said. And we stumbled out of his office and into the street.

Have you ever had the feeling, after you’ve been in a movie theater, of being surprised that you’re still in the same city that you were before you went inside? Or that it’s still daytime; or that you’re still the same person, with the same name, in the same life, on the same planet? It was like that, on the corner of Second Avenue and Seventeenth Street in New York. It was ninety-six degrees, and we couldn’t get a cab, and we couldn’t look at each other either. I heard them muttering, and there was probably even some conversation. Like “Should we walk?” “No. I can’t walk.” Something like that. But I was afraid that if I looked at them after what had just happened, they would all be complete strangers. Literally. That I wouldn’t recognize anyone. Like one of those

Twilight Zone

episodes, where everyone acts like they know you, and they do know all about you, but you’ve never met a single one of them, and you can’t understand how your life got switched around with someone else’s, or how to find your way back to your own.

Back at my apartment it was like mission control for the rest of the day. Phone calls going out and coming in. Contacting friends, relatives, and trying to come up with a plan of action. Of course the goal was to find the very best of the best, and through any means possible, to find a world-class treatment center for me. It had to be mid-afternoon by now, and since no one had eaten anything all day, Jackie and my father went out to get Chinese food. My mother was in the kitchen talking to my uncle the oral surgeon on the phone.

I sat on my bed and I cried. Not really cried, I sobbed and I screamed. I broke down in a way that I had never seen an adult go before. I sat in a room, alone, moaning and slobbering for close to an hour. And I had no frame of reference at all. For anything that was happening to me. I was twenty-four years old, and my girlfriend, Jackie, whom I’d been seeing for a year so far, had just moved into my apartment to live with me. I had already been a professional actor for most of the last seven years, and my career seemed like it was really about to take off. I hadn’t yet learned how often a career can

seem

to be about to take off. Now I know that there are careers in full flight and those that are constantly threatening to take off. I was very glad that I didn’t have one that was firmly earthbound, and I enjoyed my skips and hops up and down the runway, all the while dreaming of orbit. While understudying in the Broadway production, I had just been offered the plummest role in the national tour of Neil Simon’s play

Biloxi Blues

; I had a deal worked out to go to Israel for ten weeks to make a film with a renowned West German filmmaker; and I had a meeting scheduled for the following Monday with Warren Beatty for final casting approval on a movie that he was about to make with Dustin Hoffman. Okay, so it turned out to be

Ishtar

. It still would have been better than what I was facing.

The horror of sensing that my life was over wasn’t something that my mind could grasp. I’m not even sure that a “life,” as a separate entity, really exists. My perception was one of having been robbed, stripped bare, of every possession, liberty, freedom, hope, and dream for the future. If you added those things up, they somehow equaled my life. Maybe I’m a guy who lives with his mind racing ahead into tomorrow more than I should, but I couldn’t stop thinking that night about all the dreams and plans I had that might never be. A home, a wife, kids. Having a history to look back on. Becoming the person I wanted to become someday. Anything that I had ever said or thought before that word – “someday.” Gone. Not for me. That was my biggest fear at that moment. The absence of a future for which to endure the present.

I felt as if I had wasted enormous amounts of time in my life, and that I had to have a second chance immediately. But first I had to go into the hospital for a month, maybe more. I couldn’t even start my new beginning right away. I was going to be exiled from my history, from my future, from time itself, all in the hope of possibly regaining contact with them. Time became a concrete entity to me like never before. Never mind being more aware of it, I could’ve sculpted with it. I could have cooked it and eaten it. I felt far, far away from everything that made me

me

, I was getting homesick already, and if there was a journey that had to be made first, I wanted to start now and travel fast.

I didn’t calm down one bit until the Hunan Chicken scent hit my nose and the meat started sliding down my throat. There it was; my first lesson in survival: grief gives way to hunger.

I had the urge to tell some people what was happening to me. For instance, my sister and brother. My sister, Lillian, lived in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, with her fiance and had settled into a rather staid, solid existence as far from my life in New York as one could get. Lowell, my brother, was living a couple of hours north of the city and had been struggling to get work as a photographer. It wasn’t that Lowell lacked talent. The trouble was largely due to a neurological disorder that causes him to twitch and bark in a way that can sometimes frighten people. He’s got Tourette syndrome. He likes to call himself a Touretter. The only times he’s not twitching are when he’s sleeping or having sex. The two activities my brother swears his doctor recommends he engage in as often as possible.

My parents were very understanding of my need to speak to someone, to voice out loud what was happening to me, as a kind of reality check. If I said it to someone and they reacted, then maybe I could begin to fathom that it was really there and get prepared to live it. That kind of thing. But couldn’t I just wait to tell my brother until Monday? He had a job, a photo shoot, on Sunday, and, “He needs the work so badly, and it would be a shame to upset him so that he might not do a good job. Yes, why don’t you just call Lowell and tell him we don’t know anything yet? Then on Monday, after he’s through with his job, call him back and tell him you have leukemia.”

Wait until Monday. It was now Friday.

At first I agreed, but then I thought, No, wait a minute, goddammit. I’m calling Lowell and I’m going to tell him and let him make up his own mind what to do.

“Hey, Low’ll.”

“Evan. Hey, how you doin’?”

“Uh. Not so good, I’m afraid.”

“What’s the matter?”

“I have leukemia.”

“You what?”

“I have leukemia.”

“What do you mean you have leukemia?”

“I mean we went to the doctor this morning, and he said I’ve got leukemia.”

“Leukemia?”

“Yeah.”

“Holy shit…”

My brother is the emotional one in the family. I think that’s why my mother was afraid to let him know right away. As if, by waiting until our shock had worn off to tell him, we could avoid having to confront his shock altogether. But, as we expected, he was quite upset, and my parents’ worry was immediately doubled. Concern for my brother and his pain was like a reflex to them.

Up until the moment that I called my brother I had always believed mine was the quintessence of the “perfect American family.” Like the storybook legend of the Kennedys. Never mind that the Kennedy family history was riddled with tragedy and horror. What mattered was the success. The aura, the admirable credentials. My father had left a childhood of economic and cultural poverty behind in Bangor, Maine, to create a successful career in New York as an illustrator and advertising executive. My mother had prided herself on receiving a master’s degree and going to work long before the women’s movement popularized the trend. The children in the family had grown up either intellectual or artistic, or both. Like in the Kennedy family, my father had long before instituted guidelines that turned family interactions into pseudo-business transactions. We were paid for performing our household chores but not until we had submitted an itemized bill for the services rendered. If we wanted a raise in our allowance or in our hourly wage, a letter had to be drafted, stating the request and giving reasons to support its necessity. Not that these rules were enforced harshly or without humor. We were all, even as we obeyed them, aware of their absurdity. And for the neighbors it must have been tremendously amusing. It was not an uncommon sight to pass our house and see the three children parading around the front door shouting slogans, with placards in our grimy hands that read “Murry Handler Unfair To Workers — ON STRIKE.”

In my apartment, after Dr. Nixon’s diagnosis, I was having my first hint of suspicion that my family was anything other than perfect and enviable. Of course there was the solid marriage, and there were the artistic children surrounded by love and encouragement – no small achievements. But I now saw clearly for the first time what lurked beneath. My brother had a serious neurological impairment obvious to all outside our clan; my sister had been isolated from the family for quite a while and was planning to marry a Catholic man, a situation that caused tensions no one would have previously admitted were possible; and I had just been diagnosed with an almost always rapidly fatal disease. I became very conscious that my perception of my family, and our place in the world when we compared ourselves with others (which was what we always did, compare ourselves with others), had never really been as golden as I’d believed, and was certainly, now, anything but blessed.

It didn’t take long for us to set our sights on Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, and my mother was back on the phone, trying to arrange for my admission that night or the next morning. We had decided on Sloan-Kettering largely because I wanted to stay near my home. I had accumulated a fairly large group of friends over the years and I already expected to need them close by. Once the choice to remain in New York had been made, we were understandably seduced by the mammoth reputation of this renowned institution. We had scouted around and been quoted the name of one particular doctor there by several different sources, and we were proud of ourselves for being such educated consumers. No getting pushed around for us. We checked and double-checked. Asked other doctors about the doctor we were considering. All the signs said step one was going well.

Not that we hadn’t been warned at all. We’d been told that life inside Sloan-Kettering could be hard. It’s not the place to go to get pampered, I was told by my uncle the oral surgeon, who was doing a lot of the investigating for us. “Sloan-Kettering is a research hospital and they have a reputation for being a little short on warmth. It’s not a summer camp,” he said.

I told him, “I’m not looking for a summer camp. I’ve got leukemia and I want a doctor who’s a killer. I want someone who’s ruthless. I don’t plan on being in there but a short time, anyway.”

At eight A.M. the next morning I became patient #865770. Some strings had been pulled to get me admitted to Sloan-Kettering right away, but we were totally unprepared for the bureaucratic hell that would greet us when we checked in. I guess I had a vision of traffic being stopped on Sixty-eighth Street so the kid with cancer could pass. At least I expected to be treated as someone who was in great emotional pain and about to undergo great physical pain as well. And that’s exactly how I was to be treated – New York style.

We were herded – Jackie, my parents, and I – through a maze of corridors that were

packed

with hordes of other people. We passed people in wheelchairs; people with bandages covering their necks, their heads, their faces. Strangely gray toned people with no hair; people wearing surgical face masks; people, people everywhere. People moaning in pain. Most of the people looked tired and resigned. They seemed to understand that what was happening to them was horrible to no one but themselves.

We landed in a deserted waiting room where we sat for an hour and a half before my name was called. I was then directed to a cubicle where I faced a very young Puerto Rican woman. There was a lipstick-stained cigarette burning in an ashtray on her desk. The woman immediately began firing ridiculously mundane questions at me in a heavily accented mumble without ever once making eye contact. I thought to myself, Oh, of course. Of course. These people train at the same school as the token booth clerks. I had to ask her to repeat several of the questions over again and she would become exasperated and heave a huge sigh each time. She hated me. She really hated her job, I guess, but she was acting like she hated me. I wanted her to like me. I was, in fact, heavily invested, emotionally, in having that poor, overworked, disgusted secretary like me. Finally she said something to me that sounded like “Make a buck up to X ray, push a dove in a smocker, and wait for a technician.” She pulled a form from her typewriter, handed it to me, and reloaded, all without looking up.

After typing several more lines, she stopped and looked over at me for the first time. Once I had her attention I was so pleased that a big smile broke out across my face. She was quite pretty when she wasn’t scowling. Now she was just staring at me blankly. I said, “Thank you.”

She sat looking at me like a cow looks at you when you say “moo.”