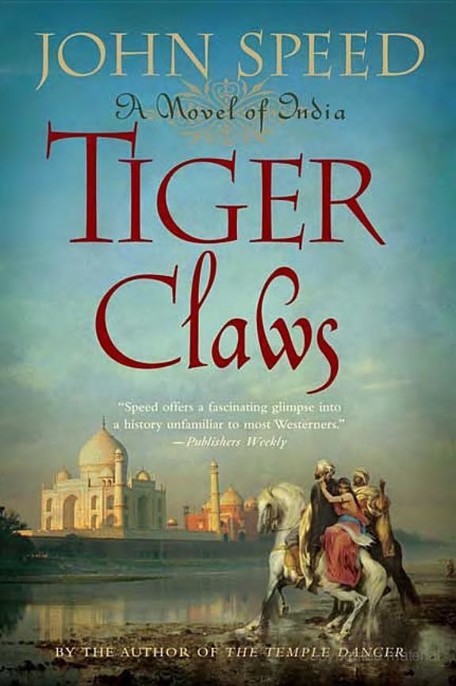

Tiger Claws

Authors: John Speed

Table of Contents

Title Page

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

EPILOGUE

MAJOR CHARACTERS IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Also by

Copyright Page

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

EPILOGUE

MAJOR CHARACTERS IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Also by

Copyright Page

The brothers say that pleasure cures all fears. But Basant’s fears are many, and his pleasures few.

The lights of the butter lamps dance like fireflies across the marble floor, stopping just short of his jewel-encrusted slippers. Time and again he has studied those lights, and the shadows their flickers form. And now Basant shrinks into a corner, praying that the dark will conceal his plump belly from the palace guards.

To cure his fear, he dissembles, though no one sees him. Basant takes pleasure in dissembling. Though he cowers in the shadows he feigns a charming smile and presses a dimpled hand to his heart, just so, as if to say:

Dear me! Did I drift off? I often daydream, here in these shadows; it is nothing special! Anyway, it is my right to be here.

Even so, he shivers, though the night is warm, and a bead of sweat carves any icy path down his neck.

Dear me! Did I drift off? I often daydream, here in these shadows; it is nothing special! Anyway, it is my right to be here.

Even so, he shivers, though the night is warm, and a bead of sweat carves any icy path down his neck.

His eyes lift to the crescent moon in the blue-black sky above the river Jumna. Far off he sees the domes of the starlit Taj Mahal, like bubbles floating above the river mist.

The brothers say that pain is but a dream. And Basant is a constant dreamer.

He dreams of a time when he knew his name.

He is a child, an orphan. He is thirsty, for he hasn’t been given even a sip of water all day. He sits on the floor of his tent, with his hands tied to a post

driven in the ground behind him. And though it is still day, his tent is dark, shut tight and hot, lit by a cheap lamp that hangs from the center pole. He knows he must be a very bad boy indeed to deserve such punishment, but he can’t think of what he’s done.

driven in the ground behind him. And though it is still day, his tent is dark, shut tight and hot, lit by a cheap lamp that hangs from the center pole. He knows he must be a very bad boy indeed to deserve such punishment, but he can’t think of what he’s done.

The tent flap opens, and the gentle men come in. Their hands are soft as they wrap cords around his torso and thighs. They speak with voices like doves, patting his hair as they tug the bindings tight.

The cords cut into his child’s flesh, and he cries out, and the gentle men shush him and call him sweet names. One of them holds a cup to his lips, and with some hesitation he drinks: it is wine, spiced wine maybe, or maybe something else. But it smells all wrong, and its bitter taste numbs his tongue; even so he drains the cup because he is so thirsty.

His mouth grows dry, and his thoughts swirl: his lips feel thick now, and they tingle; and the smells inside the tent—hot canvas and dry wool and dust—converge like harsh music; the guttering flame of the lamp above him flickers with eerie complexity.

Again light pours through the tent flap as the slavemaster enters, and with him a strange-smelling man with pale skin like a pig’s, and gray eyes. And he thinks (the way little boys think, with astonished excitement), That must be a

farang

! The boy is sure he will never forget this day.

farang

! The boy is sure he will never forget this day.

The flap drops; the tent is again dark as a cave. The cramped air is hot with hot breath. Never have so many people been in my tent, the boy thinks with pride. At a grunt from the slavemaster, the gentle men lift him up and tie him, cords and all, to a wide flat board. The

farang

’s eyes, gray like Satan’s, sparkle like a madman’s.

farang

’s eyes, gray like Satan’s, sparkle like a madman’s.

From within the folds of his robe, the slavemaster reveals a magic wand: a crescent moon of silver on a stem of jasper. The slavemaster shows it to the

farang

, and both men touch the moon, and whisper in excited voices and drag their thumbs across its edge. And suddenly it is not a wand. It is a knife. The men are testing its silver blade, a blade like the crescent moon.

farang

, and both men touch the moon, and whisper in excited voices and drag their thumbs across its edge. And suddenly it is not a wand. It is a knife. The men are testing its silver blade, a blade like the crescent moon.

The gentle men ignore the blade and the whispering, and look only at him, and pat his hands and face, and one of them begins to cry: dark trails glistening on dark cheeks. The boy has never seen a man cry before. The sight begins to scare him. There, there, he says, trying to stop those tears. Smiling for the man, There, there, he says. He doesn’t know what else to say. But the tears still come. So he floats out of his body, floats like a bubble, and the tent grows silent, as if no one dared to breathe.

Then the slavemaster takes the knife, and with a quick sweep, whispers the blade through the boy’s clothes. The gentle men tuck the tatters away,

exposing his smooth skin. He can feel the softness of their cool hands, and the ragged breath of the slavemaster on his bare stomach and bare thighs, and the cords that bite into the flesh of his legs and chest.

exposing his smooth skin. He can feel the softness of their cool hands, and the ragged breath of the slavemaster on his bare stomach and bare thighs, and the cords that bite into the flesh of his legs and chest.

He sees his tiny lingam exposed in the flickering lamplight. The slavemaster tickles it until it tingles and begins to stiffen and grow, and the

farang

chuckles, but his breath has grown raspy and his eyes blaze.

farang

chuckles, but his breath has grown raspy and his eyes blaze.

The gentle men look away. Their faces are solemn and totally elsewhere. The crying one whispers that he shouldn’t worry, that the slavemaster is an expert. It takes the boy a moment to realize that the words are meant for him. I’m fine, he says. The crying one tries to smile.

With hands now careful, the slavemaster’s thumb probes slowly along the root of the lingam and also the testicles; these he rubs between his fingers with great care. Then with expert quickness the slavemaster slides the silver moon across his smooth round belly.

The boy feels his lingam come loose, and roll, and then fall. He feels it lodge between his thigh and the board he is tied to. Where his lingam used to be he sees a tiny fountain of blood.

The slavemaster presses a heavy thumb on the fountain: his long fingers curl around the boy’s testicles. This seems to happen very slowly.

The moon blade flashes once more. The boy watches it slide in an expert silver arc.

He thinks: Someone in this room is screaming. Like a speck of down, Basant drifts around the tent, looking for the source of the screams. The gentle men are busy, pressing cloths against his bloody groin. He sees the slavemaster’s bloody palm, and on it are his testicles in the tiny sack that used to hang between his legs. (He wonders, How will the slavemaster get them back on?) The

farang

leans close, his eyes wide and his face pale.

farang

leans close, his eyes wide and his face pale.

With the curved point of the silver knife the slavemaster teases the sack, deftly slipping the testicles onto his wide palm.

The screaming stops. He stares at his tiny testicles on the slavemaster’s palm: In the lamplight they look like living gems, and he is fascinated by their colors, pinks and grays and blue. They pulse, still alive in the slavemaster’s hand.

The

farang

bending his head to the slavemaster’s palm.

farang

bending his head to the slavemaster’s palm.

The

farang

’s face lifting, eyes aflame. His swallow and his sigh.

farang

’s face lifting, eyes aflame. His swallow and his sigh.

That moment.

That pain that is just a dream.

That

Basant remembers.

Basant remembers.

The slavemaster drops the empty sack of flesh on the floor, as one might drop an orange peel.

The gentle men lift the boy, still tied to the wide board, and press his wounds with cloths. He feels his lingam roll from beneath his thigh, and wonders what will become of it. He never sees it again.

They bandage him and place him upright in a hole dug in some sand. They bury him up to his neck. He is so little, the hole is not very deep.

He stays buried three days. He gets a fever. He has never been so thirsty, so that each breath burns.

Sometimes people come to stare and shake their heads; he sees the slavemaster and the

farang

pass by, glancing at him with sidelong looks.

farang

pass by, glancing at him with sidelong looks.

From time to time the gentle men visit him, and feel his forehead and his cheeks (for all but his head is buried in the sand), and they cluck their tongues and shake their heads, and let him sip the bitter wine (but only a sip now, never a drink). Sometimes they wash his face and he licks the drips that slide down his cheek.

On the third day, using only their hands, two of the gentle men dig him out. With soft fingers they brush away the sand. They frown as they unwrap the bandages, and then smile, when they see the wound.

One produces from his turban a thin silver tube, like the quill of a feather. While the other holds him still (for his hands and feet are still tied to the board, and the cords still cut into his flesh), the man pushes the silver quill into the hole where his lingam used to be. It feels cold and enormous, but he does not cry out.

Then he feels it pop into place—somehow he knows it is in place—and he begins to pee. He pees and pees, the stream passing through the silver quill to form a puddle at his feet. Some blood is mixed with the urine. The gentle men examine the stream carefully and nod and smile some more. They release the heavy cords that tie him to the board. He collapses.

One carries him like a baby to the eunuchs’ tents.

From that day, he lives among eunuchs, travels in the eunuchs’ cart, sleeps in their tent. The gentle men who cared for him are there, and others. He thinks they must be very old. He is the only child in the tent. The slave

children he used to play with aren’t allowed. Many of the eunuchs have dark, brown skin, but his skin is like cream, golden like a lightly roasted

kachu

nut. He wonders if he will grow dark when he gets old. He makes friends with them. When one of the eunuchs is sold, he misses him.

children he used to play with aren’t allowed. Many of the eunuchs have dark, brown skin, but his skin is like cream, golden like a lightly roasted

kachu

nut. He wonders if he will grow dark when he gets old. He makes friends with them. When one of the eunuchs is sold, he misses him.

The eunuchs smile, and pat him and bounce him on their plump laps. They hide him from the slavemaster. They give him a special name—Basant, which means “springtime”—and after a while, he forgets the name he used to have.

Years later, Basant tries to remember his forgotten name. In dreams he hears it, but when he wakes, it’s gone.

Basant’s wounds heal clean, and the scars look not so bad. He carries the silver quill in his turban. He thinks it is fun to pee through; although he misses his lingam a little, he likes the silver quill nearly as much.

As they travel, rocking on the rough road in the eunuchs’ cart, his new friends tell him stories. Mostly they are in verse, and the verses are about lingams. How to rub them, how to lick them, the pleasures they can give. How odd, thinks Basant, now that I haven’t got one, to discover how pleasant they might be. The first time he hears a new verse, he laughs and laughs; they seem so silly and so clever.

When they camp at night, they teach him dances and these are easy to learn: shaking his bottom, mostly, back and forth and side to side. They make him sit on a funny seat for hours at a time; it hurts at first, but not as much as the knife, and then it scarcely hurts at all, even when they enlarge each day the nasty part that squeezes into his little bottom.

Sometimes Basant sees the eunuchs speaking with the slavemaster. Basant thinks it odd that the slavemaster should look at him as though he were a sack of gold waiting to be emptied onto the slavemaster’s wide palm. He sees the

farang

sometimes, hiding behind a tent, snatching glances.

farang

sometimes, hiding behind a tent, snatching glances.

One night they set up camp in a big town with a big domed mosque. The eunuchs dress him in satins and silks; they rub his

kachu

skin with perfume and stain his eyelids with kohl. They lead him to a special tent, with walls of fine red silk and velvet cushions and butter lamps, and they place him on a soft bed plump with cushions. It is the finest tent he ever has seen. One by one the eunuchs kiss him and duck out through the curtains until he is alone with only the flickering butter lamps for company. Wisps of incense curl through the air, but he can’t find where.

kachu

skin with perfume and stain his eyelids with kohl. They lead him to a special tent, with walls of fine red silk and velvet cushions and butter lamps, and they place him on a soft bed plump with cushions. It is the finest tent he ever has seen. One by one the eunuchs kiss him and duck out through the curtains until he is alone with only the flickering butter lamps for company. Wisps of incense curl through the air, but he can’t find where.

He is puzzling about this when the

farang

comes into the tent.

farang

comes into the tent.

It is not pleasant.

Soon Basant finds he understands the answers to many puzzles. He understands with great suddenness, as one understands a fall down a well, or a fist to one’s nose. He understands it all.

Then, after an eternity of night, he falls asleep, and thankfully he has no dreams. The next morning the

farang

is gone, and only then does he weep.

farang

is gone, and only then does he weep.

He wipes the trails of his kohl-stained tears, and with some difficulty walks to the eunuchs’ tent. He hears them inside, but no one comes out to greet him. He stares at the flap, unable to enter. Instead he goes to the bathing place and washes himself, using bucket after bucket of cold water.

Other books

A Bloody Good Secret: Secret McQueen, Book 2 by Sierra Dean

Romance of the Snob Squad by Julie Anne Peters

Jeanne G'Fellers - No Sister of Mine by Jeanne G'Fellers

My Losing Season by Pat Conroy

Dolphins! by Sharon Bokoske

Hana's Handyman by Tessie Bradford

A Friend of the Family by Lisa Jewell

Amazon Burning (A James Acton Thriller, #10) by J. Robert Kennedy

First Contact - Intergalactic Stories by Bane Bond