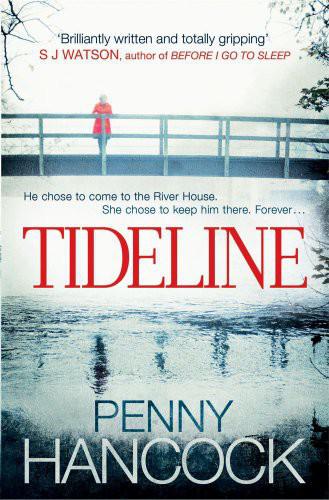

Tideline

Authors: Penny Hancock

Tags: #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Psychological Fiction, #Family Secrets, #Fiction

Penny Hancock grew up in south-east London and then travelled extensively as a language teacher. She now lives in Cambridge with her husband and three

children. This is her first novel.

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright © Penny Hancock, 2011

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Penny Hancock to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act,

1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray’s Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

A CIP catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84983-768-2

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-0-85720-627-5

E-book ISBN: 978-0-85720-629-9

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

For Pauline and Peter

Friday

Sonia

He comes to me when the chatter of school children along the alley has died away. Later, drinkers will troop the other way towards the pub, the evening riverbus will make its

last journey westwards to town, rattling chains and making the pontoon groan. But this is a silent time, almost as if the river and I are waiting.

He comes to the door in the courtyard wall.

‘Sorry,’ he says, twisting awkwardly about, such a graceful body but he doesn’t yet know what to do with it. ‘It’s just, at the party, your husband mentioned about

that album.’

I stare past him. Early February, the light in the sky loosening. I smell brewery yeast drift on the breeze from downriver. Bitter Seville oranges from the marmalade I’m

making in the kitchen. Along with the bubble of the preserving pan behind me, I hear Cat Stevens singing ‘Wild World’ on the radio. Time flips and catches in a tangle in my head.

I look into his face.

‘Come in,’ I say, ‘Of course. Remind me . . .’

‘It’s by Tim Buckley. You can’t get hold of it any more, not even on the internet. He said he had a copy on vinyl. D’you remember? I’ll record it and bring it

back.’

‘No problem.’ I speak as if I were his age rather than my own. ‘Cool!’ Then cringe inside. I can hear Kit. ‘Oh God, Mum, don’t try and speak as if you were

sixteen. It’s sad.’

He comes in. He steps through the door in the wall. The wisteria’s a black steel scribble like the barbed wire they loop along the top of prison fences. He follows me across the courtyard

and over the threshold into the hall. As well as the oranges there’s the smell of the wax floor polish that Judy uses. He comes into the kitchen. Goes to the window, looks at the river. Then

turns and faces me. I won’t deny it, the thought flits across my mind that perhaps he’s come because he finds me attractive. Young boys and older women, you do hear of such things. But

I pull myself together.

‘I was just going to have a drink,’ I say, turning down the flame under the marmalade which is bubbling ferociously now and must have reached setting point. ‘Have

something.’

I never usually drink before six, but I wave bottles recklessly at him, vodka – I know teenagers love vodka – Greg’s beer, I even hold up a bottle of red wine we laid down,

years ago, waiting for it to mature so we can open it on Kit’s twenty-first birthday.

He shrugs. ‘OK,’ he says. ‘If you’re opening something.’

‘What would you

like

though,’ I insist. ‘Go on, say.’

‘Red wine then.’

The thing with boys of this age is they do speak but you have to ease them into it. I know that from Kit’s friends who tramped in and out, day and night, for several years before she left.

Those boys were all spots and hair over their eyes and big feet. Silent except for the pleases and thank yous drummed into them by their parents. You had to tease and mention bands to get them to

talk. Jez is different. With Jez, I don’t have to try. He’s easy to be with. For a teenager he’s quite unself-conscious. It must be to do, I think, with his living in France. Or

maybe it’s because we feel we know each other, though we’ve barely spoken before.

He moves from the window and sits at the kitchen table, one foot crossed over the other long leg, the huge sole of his trainer almost in my face. These children today, these boy-men, did not

exist quite like this when I was young. They’ve evolved since then. With their well-mixed genes, they’re more adapted to the modern world. Taller and broader. Softer. Gentler.

‘This is a wicked house. Right by the river. I wouldn’t sell it.’

He drinks half his wine in one mouthful. ‘Though it must be worth quite a bit.’

‘Oh, well, I’ve no idea what this house is worth,’ I say. ‘It was in the family. My parents stayed here for years, all their married life virtually. I inherited it when

my father died.’

‘Cool.’ His wine’s gone in one more gulp. I refill his glass.

‘This is the kind of place I want to live,’ he says. ‘On the Thames, a pub to the right, the market there. You’ve got everything. Music shops. Venues. Why d’you

want to move?’

‘I’m not going anywhere,’ I assure him.

‘But your husband, at the party, he . . .’

‘I’ll never leave the River House!’

This comes out more curtly than I intend. But I’m hearing things I don’t like. Greg thinks we should move, yes, but we haven’t agreed to it. ‘I never would. I never

could,’ I say, more softly.

He nods.

‘I didn’t want to leave this area either. But Mum says London – Greenwich especially – is bad for my asthma. It’s one of the reasons we went to Paris.’

His dark fringe has fallen across one eye. He flicks it back, and looks at me from under long, perfectly formed black eyebrows. I notice his sinuous neck with its smooth Adam’s apple.

There’s a triangular dip where his throat descends towards his sternum. His skin has a sheen on it that I’d like to touch. He’s of adult proportions yet everything about him is

glossy and new.

I want to tell him that I have to stay in the River House to be near Seb. Somewhere in the river’s swell, in its daily ebb and flow, he’s still there, a flash of multicoloured oil on

its surface. A ripple, a bubble, a shooosh, and he’s back. I’ve never told anyone this. It’s something few people would understand, and, to use a cliché, so much

water’s gone under the bridge since then. A whole lifetime. I’m convinced Jez would get it. But I let the moment pass. Something prevents me from telling him. It’s something

that’s so close up, I can’t get it into focus. Instead, I say, ‘Living in Paris. That must be exciting?’

‘It’s OK. But I miss my mates and the band. I’m coming back soon anyway. Been looking at colleges. Music courses and stuff.’

‘Your aunt said.’

‘Helen?’

‘Yes.’

A flicker of irritation that he calls her Helen. At the intimacy of it. Which is silly. No one calls their aunts ‘Aunty’ any more. What did I expect?

‘Found anywhere you want to apply to?’

He pulls a face and I can see he doesn’t want to have this conversation, the one where the adults ask what you’re going to do. He’s too alive for this kind of talk. Even though

I’m thinking, I could help you. Drama, music, they’re my areas.

‘Everyone says, “Oooh Paris,” but it’s rubbish, a city where you have no mates. I prefer London. It’s like no one gets it when I say that.’

‘I get it,’ I say.

I’m aware of the marmalade slowly setting on the stove. I should fetch the funnel and pour it into jars, but I’m unable to move from my chair, from his line of vision.

‘You can nip up and get the album if you like,’ I say. ‘It’s in the music room right at the top of the stairs.’

‘The room where the keyboard is?’

Of course. He came here once before, I remember now, with Helen and Barney, one or two years ago. It was summer. His voice an octave higher, pink cheeks. A girl glued to him. Alicia. I barely

registered him then.

He doesn’t move.

‘You still doing stuff with those actors and all that?’ he asks. ‘It’s sick.’

‘What?’

When he grins, his mouth is wider than I’d realized. I have to clutch the edge of the chair to ensure I maintain my composure.

‘Sick. Cool. All those actors you meet. All those TV people. What’s your job again?’

I train voices, I tell him. He wants to know what that means, what it involves. I try to explain how the voice can emphasize meaning when words are inadequate. On the other hand it can

contradict what’s actually said. This is useful for actors of course, but for real life, too.

As I speak he listens in a particular way. I find this more disconcerting than anything. He listens the way Seb used to, eyes half closed. Reluctant to admit his interest. A half smile on his

lips.

The bottle of wine is almost empty. The marmalade must have solidified in the pan.

‘I guess you know some famous people. Any rock stars? Any guitarists?’

‘No rock stars as such. But I know some . . . useful people. People who are always looking for new talent.’

He leans towards me a little, and his eyes widen. Brighten.

I’ve found what drives him.

‘I want to be a professional guitarist one day,’ he says. ‘It’s my passion.’

‘Well, when you get the album, you could bring one of Greg’s guitars down. There’s quite a selection up there.’

‘I ought to go,’ he says.

Of course he must go. He’s a fifteen-year-old boy. On his way to meet his girlfriend, before he gets the train from St Pancras back to Paris tomorrow morning.

‘She makes me meet her in the foot tunnel exactly halfway between south and north London.’

‘Makes you?’

‘We–ell,’ he looks at me and all of a sudden he’s just an embarrassed teenage boy after all.

‘We measured the halfway point,’ he says, ‘by counting the paving slabs. We were going to count the white bricks but there were too many.’

‘How old is she?’ I ask.

‘Alicia? She’s fifteen.’

Fifteen. So. She’ll have no idea that nothing will ever be like this again.

‘I’ll go and get that album,’ he says, stumbling a little. The wine has gone straight to his head, he’s what Kit would call a lightweight.

‘Have one more drink. I’ll pour it while you go up. Go on. Go up.’

I listen to his footsteps taking the stairs two at a time and open another bottle. Something cheap this time, but Jez won’t notice. I fill his glass, and I add a little whisky. A cloud

shifts over the river and a last sliver of sunlight slides across the table. For a second the glasses, the bottles and the fruit bowl are suspended in a rich amber glow.