Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (4 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

The young Stefan found the dining arrangements here thoroughly

humiliating. Instead of eating with the adults in the main dining room, as

he was used to doing at home, the children ate in a separate, smaller dining

room. There were other children there, together with their governesses—but this exclusion from the world of his parents ran completely counter to his normal view of life.

When they came to the end of their time in Marienbad the family moved on with their retinue to one of the popular holiday resorts of the day, either by the sea or up in the mountains. In the mid-1880s their destination of choice was Selisberg on Lake Lucerne. In later years the Zweigs travelled as far afield as the Belgian coastal resort of Blankenberghe and Innichen in the South Tyrol. A trip on the Rhine in the summer of 1884 must have made such an impression on the young Stefan—who was not even three years old at the time—that when he visited Mainz thirty years later he astounded his hosts by his detailed recollections of the city as it had looked back then, before the original railway station near the River Main had been replaced by a new building in another part of the city.

10

With Stefan’s enrolment in the primary school in the Werdertorgasse in 1887 his circle of contacts expanded for the first time beyond his immediate family, for as a child he had had very little to do with children of his own age, apart from his brother and a few cousins. Stefan was a good pupil, but in his early years at school he did not stand out from his classmates as being special or gifted in any way. But at least the good marks he received for ‘General behaviour’ suggest that he did not make a bad impression either. And yet he never took to school the whole time he was there. He was only thankful that he learnt to read at an early age, and thereafter could escape into alternative worlds. We do not know, unfortunately, what books, if any, were read in the family home. The family took a daily newspaper, of course, and there will have been some books in the house. It seems likely at least that a man with artistic interests like Moriz Zweig will have spent some of his leisure hours reading the literary classics. Certainly the two sons kept a small library of books during their childhood and youth, which, in addition to the texts they needed for school, contained all manner of modern works—including Friedrich Gerstäcker’s tales of adventure in far continents, and the works of Charles Sealsfield. The two Zweig boys were also acquainted with Julius Stettenheim’s indestructible war reporter Wippchen, as well as Winnetou, Old Shatterhand and Kara Ben Nemsi from Karl May’s recently published novels. Stefan was particularly taken with a book whose author and title he could not recall in later years, but whose contents remained imprinted on his mind: it was a colourful account of travels in Mexico and the distant countries of South America.

NOTES

1

Stefan Zweig to Hermann Hesse, 2nd March 1903. In: Briefe I, p 57.

2

See for example Prater/Michels 1981, Fig 11. Stefan Zweig also wrote his father’s name consistently as “Moriz”, cf Zweig 2005, Figs 9–16.

3

28th December 1915, Zweig GW Tagebücher, p 242.

4

Alfred Zweig: Familiengeschichte.

5

Alfred Zweig: Familiengeschichte.

6

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 24.

7

Zweig 1927, p 7.

8

Rieger 1928, p 23.

9

Brennendes Geheimnis. In: Zweig GW Brennendes Geheimnis, p 27.

10

Frank 1959.

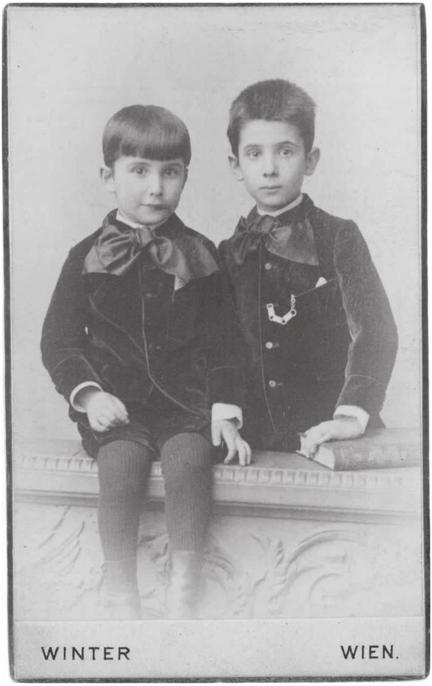

Stefan and Alfred Zweig

To see in them a set of youths who never put down the lyre, so to speak, would not be entirely correct.

1

Friderike Zweig

T

HE SONG ABOUT “HAPPY

, blessed childhood” that Stefan Zweig had to learn in one of his early years at school tells a completely different story to the account he later gives of this time in

Die Welt von Gestern

—school was boring, soulless and dull. Even when approaching the age of sixty he could not recall a single happy memory. So much time had passed, yet he could not even bring himself to see his teachers as figures of fun. Not that they were colourless ciphers—far from it. It was just that the routine of school life, which had followed the same sacrosanct pattern for decades, had so accustomed them to a rigid, authoritarian style of teaching that they simply reeled off the antiquated syllabus and took no account of their pupils as individuals. The teachers had long since accepted this system, and their pupils accepted it sooner or later as well—at least, that’s how Zweig presents it in retrospect. At the height of his distrust of the authoritarian school system he even goes so far as to observe, in an allusion to the work of Sigmund Freud, that it is no coincidence that it was a former grammar-school pupil who chose to study the origins and consequences of inferiority complexes at such length.

After primary school Zweig attended the Maximiliangymnasium, later renamed Wasa-Gymnasium, for the eight years from 1892 to 1900. His accounts do not go into detail about the teaching as such, though we do learn something about the syllabus. In their classes on literature, a subject that was already of special interest to him, they had to listen to well-worn lectures from the teacher with titles like

“Schillers Naive und sentimentalische Dichtung”

the same lectures he had been giving for decades. The syllabus made no allowance at all, he tells us, for the study of more modern authors such as Baudelaire or Walt Whitman, let alone contemporary writers.

Zweig’s later close friend, the writer Felix Braun, who attended the same school a few years after him and was taught by the same teachers,

offers a rather different perspective. He credits German teacher Professor Lichtenheld with having introduced him to classical and modern literature and thus pointing him in the direction of his future career. Of this same teacher Zweig, on the other hand, says in typically over-egged fashion that he was a “decent enough old chap”,

2

but he had never even heard of Nietzsche or Strindberg, whose works the boys read in secret behind their desks.

Then again his classmate Ernst Benedikt does his best in his memoirs to put a more cheerful gloss on these years when he tells us he can still hear Stefan’s “soft, giggling laughter at the unintentional and irresistible drollness of our Latin teacher, whose stocky, satyr-like build [ … ] and malapropisms were still a source of merriment to us years after we had left school.”

3

The teacher in question, Karl Penka—or Penka Karl, as he called himself—had written a number of academically respected works with titles such as

Die alten Völker Nord- und Osteuropas und die Anfänge der europäischen Metallurgie

[

The Ancient Peoples of Northern and Eastern Europe and the Beginnings of European Metallurgy

]

and Origines Ariacae. Linguistisch-ethnologische Untersuchungen zur ältesten Geschichte der arischen Völker und Sprachen

[

Origines Ariacae. Linguistic-Ethnological Studies in the Ancient History of the Aryan Peoples and Languages

]. That these dusty topics excited little or no interest among his pupils was, and remains, hardly surprising.

In 1922 Zweig received a warm invitation from the school to its fiftieth anniversary celebrations. But instead of attending the festivities as guest of honour and giving the requested speech, he exacted a belated vengeance by writing a poem for the souvenir publication that left no doubt about his feelings: “We called it ‘school’, and meant ‘learning, fear, strictness, torment, coercion and confinement’,”

4

we read in the opening lines. The following verses concede that when we leave school we still find “nets laid thick about our will”, but the overall tenor of the poem is that school, and the constraints of school, are a poor preparation for life.

At the age of thirteen Zweig gave up learning the piano, having realised by now, despite intensive practice, that he would never attain the perfection of his father, who could play even the most difficult pieces by ear, without a score. To spare himself further disappointment, and because he preferred to spend his time reading literature anyway, he managed to persuade his parents to stop his piano lessons. We do not know if he ever played a musical instrument again. A number of years were to pass before he took a serious interest in music again, although he went to the occasional

concert. His father, on the other hand, was and remained a passionate music-lover; he had once attended a performance of Richard Wagner’s

Lohengrin

conducted by the composer himself, and was still talking about it decades later. When his wife could no longer accompany him because of her hearing problems, Moriz Zweig was frequently seen heading off to the opera or theatre with his two sons in tow.

When it came to ice skating, dancing and riding a bicycle (which he never learnt to do all his life) Stefan showed as little aptitude as he did for all athletic pursuits—and even less interest. No evidence has been found to support the claim that he worked as a swimming instructor during his time at school and university at the Jewish sports club Hakoah Wien.

5

Since he did not feel particularly drawn either to Jewish associations or to sports clubs, and since he certainly had no need of the income, the claim can safely be dismissed as a rumour. Let us hope so at least, given that he did not even learn to swim until long after his student days were over …

He had started to collect stamps during his early years at school. At the age of twelve he switched with the same enthusiasm to collecting autographs, which promised to be a lot more exciting. Wherever and whenever they could, Zweig and his classmates stalked their victims at the stage doors of the city’s theatres and opera houses. Vienna was well blessed in those days with theatrical venues, and actors and singers were universally revered as gods—which made the boys’ forays a great deal easier. Gripped by a genuine mania for all things theatrical, even the grown-ups were keen to sniff out every last detail of their favourite performer’s professional and private lives. This was taken to ludicrous extremes, as Zweig later describes in

Die Welt von Gestern

:

To have seen Gustav Mahler in the street was an event that one proudly reported to one’s schoolmates the next day as if it were some kind of personal triumph, and when as a boy I was once introduced to Johannes Brahms, and he patted me affably on the shoulder, I went around for several days with my head in a spin as a result of this momentous occurrence. At the age of twelve I had only a very vague idea of what Brahms had accomplished, but the mere fact of his fame, and the aura of creative genius, had a shattering effect on me. A new play by Gerhart Hauptmann in the Burgtheater got our whole class worked up for weeks before the rehearsals began; we would sneak up on actors and extras in the hope of being the first to discover the plot and the cast—before anyone else! We even had our hair cut at the Burgtheater barber’s shop—such were the ridiculous lengths to which we went—simply in the hope of picking up some tittle-tattle about Wolter or Sonnenthal; and a boy from one of the junior classes was once specially cultivated by us older boys and bribed with all kinds of little favours simply because he was the nephew of a lighting superintendant at the opera house, and he sometimes smuggled us secretly onto the stage during rehearsals—where the thrill we felt, setting foot on that stage, was more than Dante felt upon entering the heavenly spheres of Paradise.

6

Pursuing actors and singers was one way of adding to his autograph collection; the other was to write to famous authors and ask them for an inscription or an album piece. Zweig must have fired off many such requests in all directions, and eagerly awaited the arrival of each day’s post. But to his disappointment he received virtually no answers to his letters. In desperation he had the idea of calling himself “Stefanie Zweig”, thinking that a woman would be more likely to receive a reply; but this proved to be a fallacy, as the continuing lack of post demonstrated. When eventually he had a reply from Julius Stettenheim, he received not only the handwritten poem he had hoped for, but also the solution to his problem, wrapped up in verse:

As cheap as popularity comes

It’s not as cheap as some might think.

One’s asked to write a line or two

But in the letter so silver-tongued