This Must Be the Place (15 page)

LOT 27

LOT 28

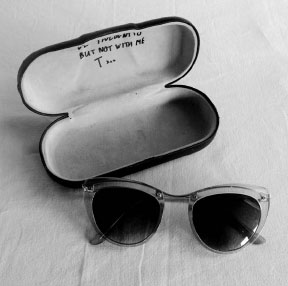

PAIR OF SUNGLASSES

Given to Wells by Lindstrom. Rose-coloured frames, dark brown lenses. Good condition, scratch measuring 2mm on right arm. Case has leather outer and felt inner. Dented and shows signs of use and sun damage.

Written inside the lining is:

Be incognito but not with me. Txxx

LOT 28

LOT 29

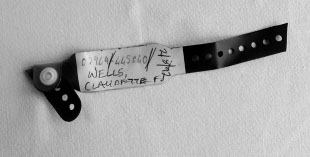

HOSPITAL ID BAND

Red plastic, severed for removal, inscribed in black ballpoint:

WELLS, CLAUDETTE F

. 2/8/93

A medical number is also inscribed in blue ballpoint. NB: various newspapers at the time reported a rumour that in the summer of 1993 Wells suffered a collapse during filming and was admitted to a New York hospital with ‘stress-related exhaustion’.

LOT 29

LOT 30

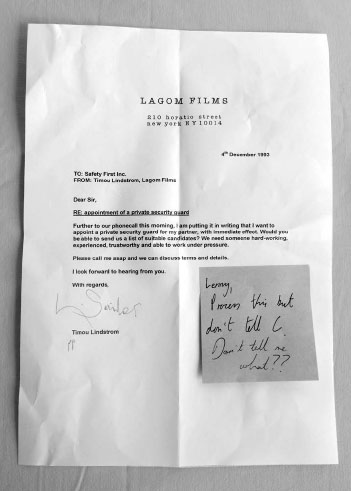

LETTER TO A PRIVATE SECURITY COMPANY

From Lindstrom, dated 4 December 1993, indicating that he wished to appoint a private security guard for Wells. The letter is on headed paper from Lagom Films, Wells and Lindstrom’s production company, and is signed in Lindstrom’s absence by personal assistant Lenny Schneider. Written on an attached sticky note, in Lindstrom’s handwriting, is:

Lenny, process this but don’t tell C.

Underneath, in Wells’s handwriting,in black ballpoint, is:

Don’t tell me what??

LOT 30

How a Locksmith Must Feel

A phone call, California to Donegal, 2010

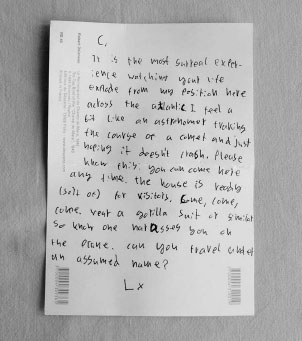

‘C

laudette?’

She has picked up so quickly that he thinks she must have been waiting by the phone.

‘Daniel.’ It is half sighed, half murmured. ‘About bloody time.’

Despite his surprise at this greeting, despite everything, he finds himself wincing, hoping the children aren’t in earshot. Marithe has a far more colourful vocabulary than any six-year-old ought to have; Claudette’s inability to refrain from swearing in front of their children is his one and only complaint about her as a mother. And one, he tells himself, over and over, isn’t so bad.

‘Hello to you too,’ he says, nonplussed. ‘Are you OK?’

He hears the sound of the television surge forward, then die away, and he can picture her, knows exactly where she is in their house, what she is doing: she is walking away from the sitting room, where the wood-burner will be fired up, where the dog will be lying, stretched out like a hairy hearth-rug, where Marithe and Calvin will be sitting, leaning up against each other, on the sofa, Marithe with her thumb in, slackly, watching cartoons. Claudette will be heading, on bare feet, over the splintery boards of the corridor into the front room, where she can swear at him with impunity.

The urge to be there with her is so strong he has to lean his head into a convenient lamp-post, grit his teeth, set his jaw.

‘Am I OK?’ she says. ‘Well, frankly, I’ve been better. The question is, are you OK?’

‘I’m fine,’ he says. ‘Why wouldn’t I be? I was just calling to let you know that I’m not at my dad’s yet. I kind of—’

‘I know you’re not at your dad’s,’ she interrupts.

‘You do?’

‘Yes. Your sister called me and –’

‘Ah.’ There is a rising sensation in his chest, a small tide of dismay. He should, he now sees, have called her before. He should have tried to explain something to her, about the holes in his life, the underground rivers, about the sudden towering urge to fix as many as possible.

‘– told me you’d just taken off. There they were, waiting for you in Brooklyn, making lunch for you, when you sent some incoherent text message saying you were at Newark airport but that you weren’t going to be able to make it that day.’

‘Now,’ he says, swallowing, ‘about that. The thing is, I meant to go. Obviously. I really did. I mean, I was there, wasn’t I? But then—’

‘Where are you?’ she says. Her voice is low, forlorn, and the sound of it fills him with nothing so much as the desire to put his arms around her, to hold her head to his shoulder.

‘Fremont,’ he mutters.

‘Where?’

‘California.’

A sharp intake of breath. He listens to the ensuing silence. There is my home, he thinks, there is the noise of my house, the lives of my wife and children. He wants to bottle this sound, to stopper it, so that he can take it out and give himself a dose of it, when needed.

‘I caught a plane straight out of Newark for San Francisco.’

‘But … what happened to New York?’

‘I did go. I was there. And I’m going back there now. Right now. I’m heading to the airport to catch a flight back tonight. The party’s not until tomorrow. I’ve got loads of time.’

‘Daniel, what are you doing in California?’

‘I …’ He presses his fingertips into his eye sockets. ‘I had to … I wanted to see … my kids. My other kids. I had this sudden … I wanted to straighten things out with them.’

‘Oh,’ she says, taken aback. This is clearly not the answer she was expecting. There is a moment of silence. ‘And did you manage to see them?’

‘I did. I saw them just now.’

‘That’s great, Daniel. That’s wonderful. I’ve always said you should just turn up. How did it go?’

‘It was …’ He tries to articulate what he felt when he saw them, after a gap of so many years, how they appeared in the doorway of the coffee shop and walked towards him across the floor. It wasn’t so much a case of recognition, more a sensation of rightness, the idea of something being where it should be, something finding its place. He knows now how a locksmith must feel when he creates the key that finally releases an old rust-shut lock, or a composer when he finds the note to complete a chord. They had changed, Niall and Phoebe, yet were exactly the same and he, Daniel, had been filled with a crazed kind of delight and delirium at seeing them, their hair, their hands, their feet in their shoes, the way their clothes sat on their bodies so precisely and so uniquely. Your

faces

, he had wanted to exclaim, your

fingernails

. Just look at you both.

In several years’ time, in the middle of the night, Daniel will receive the news that Phoebe has been killed in an accident and he will find that during her funeral he will be picturing her as she was on that day in the coffee shop, sitting before him after so long, her hair hooked behind one of her perfect pale ears, a charm bracelet encircling her wrist, her knee almost touching her brother’s.

As yet, of course, he doesn’t know this. Nobody knows this. He doesn’t know that he will receive emails from her once a week for the rest of her life, that he will, for that short time, see her regularly, her flying to Ireland, him flying to the States; he will take her out to dinner, she will order for both of them, they will discover a mutual taste for spicy Thai soup; he will buy her the books she needs for college, a warm winter coat, a pair of leather gloves. For now, Daniel is walking along a Fremont street and he is raising himself up on his toes to answer his wife, banging his hand into the wall of a laundromat. ‘I saw them,’ he is saying, with unadulterated, unalloyed joy. ‘They came, Claude. And they were amazing, as amazing as they ever were.’

‘I’m really pleased for you. Really, really pleased.’

‘Thank you.’ He sighs, touched by her support, her understanding, her calm. Everything, he sees, is going to be all right.

Then she says, ‘Could you not have told me first?’

‘Well, the thing is—’

‘Could you not have called to tell me why you didn’t turn up in Brooklyn? Could you not have been a little bit more forthcoming in the single text message you deigned to leave on your sister’s phone? Could you not have let us all know before?’ And here it comes, he thinks, the emotive articulacy that movie-goers paid to see. ‘It’s your father’s birthday, Daniel. He’s a frail old man and he was expecting to see you yesterday. I know there’s a lot of history between the two of you but he didn’t deserve that. Not at all.’

Silence roils between Fremont and Donegal.

‘I’m sorry,’ he says. ‘You’re right. I should have called you. I don’t know what I was thinking. It’s hard to explain but I’m kind of as surprised as you are to find myself—’

‘Is this about someone else?’

‘What?’

‘Are you seeing someone?’

‘Claudette. That’s ridiculous.’

‘Is it?

‘Yes.’

‘Because you’d never do a thing like that, would you?’

He sighs. ‘I admit that my track record in that respect is not perfect but, come on, you know I wouldn’t do that to you. Who else would I ever want?’

She lets out a puff of air. ‘I don’t know.’

‘Come on, I’m not that man.’ He wants to say, aren’t you mixing me up with your ex, but he can see that this isn’t the time, so instead he opts for more reassurance: ‘Sweetheart, I swear to you it’s not that.’

‘Swear on your life.’

‘I swear.’

‘On the children’s lives.’

Unseen by her, he smiles. He loves her for her sense of melodrama, her extremity. ‘I swear on the children’s lives.’

‘OK,’ she says slowly and clearly. ‘Know this, Daniel Sullivan: if I find out that you are lying to me –’

‘I’m not.’

‘– I will cut off your balls.’

‘OK.’

‘First one, then the other.’

‘Got it.’ He hears himself emit a slightly nervous laugh. ‘Thank you, wife of mine, for that very graphic and precise picture.’ He dodges a man holding the leashes of no fewer than five dogs and sidesteps a leaking gutter. ‘So,’ he says, in an attempt to get the conversation back to the realm of normality, ‘what have you guys been doing today? Anything special?’

‘Well,’ Claudette says, ‘remember I told you I wanted to try to build that winch? I realised—’

‘That what?’ He isn’t sure he heard her right.

‘Winch. I realised—’

‘Did you say “winch”?’

‘Yes, the winch. We talked about it last week.’

‘We did?’

‘When we were out by the well that evening. With a bottle of wine. Remember?’