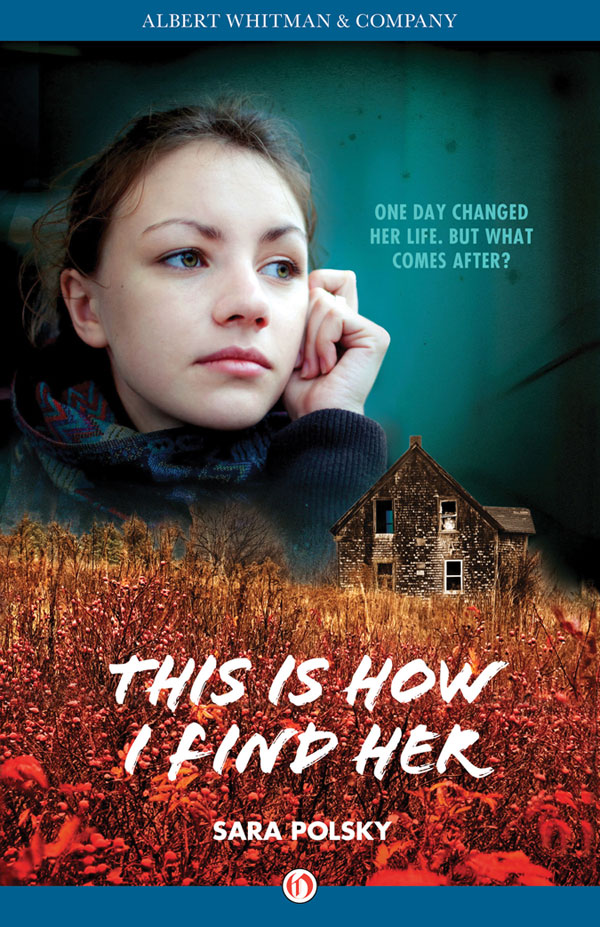

This Is How I Find Her

Read This Is How I Find Her Online

Authors: Sara Polsky

Sara Polsky

ALBERT WHITMAN & COMPANY

For my family.

One

On the fourth day of junior year, sometime between

the second bell marking the start of chemistry class and the time I got home from school, my mother tried to kill herself.

â

This is how I find her:

I look for her when I come home, the way I always do, to say hello and tell her about my day. I head for her studio, which is what we call the little concrete-floored storage room in the basement of our building with our apartment number in marker on the plywood door. Our neighbors use their rooms for old chairs and crooked piles of boxes. Ours is almost empty except for my mother's easel in the center of the room and her paintings stacked against the walls. There's an ancient dresser next to the door, full of paints and colored pencils, paper clips and rubber bands and spare keys. The smell of paint hangs in the air and drifts under the plywood into the hallway.

The studio door is unlocked and I push it in without knocking, not wanting to interrupt my mother's work. A thin beam of light streams in from the window, not enough to paint by, and bright lamps in each corner cover the canvases in shadow and light. I expect to find my mother in her usual position, listening to classical music with the volume all the way up, right hand gripping her paintbrush, left hand moving as if she's conducting the violins and violas right through her stereo. She was there when I left for school this morning. She's been there every day and night for weeks, hardly sleeping, just painting.

My mother always paints when she's manic.

But not today. The studio is empty except for the half-done painting sitting on the easel, a blur of strong colors that looks to me like a woman running along a sunset beach. I can't tell whether the woman is fleeing or chasing.

Something about the painting feels off-balance to me, like a sentence stopped in the middle.

“Mom?” I ask, even though I can see she's not here.

I shut the studio door and head for the stairs in a walk that's almost a run. The painting looks abandoned in the empty, unlocked room.

My backpack thumps against my back, my shoes slap unevenly against the steps, my breath huffs out, all in the rhythm of

hurry, hurry, hurry

. Some kids barrel into the stairwell on their way to play in what passes for a yard outside our building. I stumble into them and grab onto a higher step. One of the kids, a neighbor I babysit after school sometimes, calls out to me, but I don't answer. As soon as they're out of sight, I move even faster.

Hurry, hurry.

My leg muscles start to burn.

Finally, I get to the top floor, second-to-last door. I unlock it and rush into our apartment, my backpack still on. The place is chaotic. Since school started, I haven't had a chance to clean, and my mother never does. There's a trio of used coffee mugs on the table where we keep the mail, next to a teetering pile of envelopes and magazine subscription cards. My feet crinkle against shiny scraps of paper on the carpet. They're everywhere, as if a blizzard's worth of shredded catalogs snowed in our apartment while I was at school. I imagine my mother cutting them up, planning some kind of collage.

Where is she?

“Mom?” I ask the empty air of our apartment. Then I shout. “Mom!”

She doesn't answer. I move faster, toward the bedroom with her queen-sized bed in one corner and my twin bed in the other. My stomach swoops with nerves. Would I rather find her there or not know where she's gone? I'm not sure, and my feet keep moving forward without giving me a chance to think about it.

But when I get to the bedroom, my eyes get stuck on the numbers on the bedside clock. The clock face and I stare at each other, a contest I know I'll lose, for seconds that feel longer than they are. My eyes must know something the rest of me doesn't, because they won't let me look just those few inches farther to the left, toward my mother's bed. It's 3:34 p.m. The colon blinks at me: 3:34.

“Mom?” I say again.

There's still no answer, and when I force my eyes away from the clock, the first thing I see are her legs, dangling off the bed from the knees down, feet stopped just a few inches short of the floor as if resting themselves on the solid silence instead. I follow her legs upward to the rest of her, slanted across the bed, her head half on one pillow. Her eyes are closed, hair hanging ragged and long past the pale face I've noticed getting thinner again in the last few weeks. Her breath is so shallow I can't tell it's there at all until I put my ear right up against her mouth. Then some air tickles my cheek. I don't laugh.

When I look up, my hair drops off my shoulder and brushes against my mother's face. She doesn't stir.

There are the pills right in front of me. A few spill across her night table from a prescription bottle I don't recognize, its twisted-off childproof cap sitting nearby. And there's the glass. Just a regular kitchen glass with an inch of tap water at the bottom.

Terror crawls up through my stomach, stretches along my throat, and creeps into my mouth as I reach for the phone and press three numbers.

“My mom,” I think I say, and “pillsâ¦half a bottle⦔

Somehow, I get out enough complete thoughts to communicate the nature of my emergency. I confirm my address. Then I climb onto the bed, scrambling like a child much smaller than I am, and grab my mother's hand. I hold it until the sirens come.

Two

“Would you like us to call someone for you?”

There's a nurse in mint-green scrubs standing in front of me, and I sit up so fast I bang my head on a poster. The frame rattles against the wall behind my head. Metal. I can't seem to take a deep enough breath, and my stomach turns over while I wait for the nurse to tell me how my mother is doing.

“Oof, that looked like it hurt,” the nurse says instead. “Are you all right?”

Her words travel to me slowly, warped like I'm hearing her from the other side of a pane of glass. I blink. I'm in a hospital waiting room, on a tough vinyl chair with a hole in the seat. Before that I was in an ambulance, rocketing from my apartment to here. How did I get from that ambulance to this chair?

There are more important questions that crowd that one out. Will my mother be okay? Where is she right now? Where did she get that bottle of pills?

Why didn't I know she had it?

“Your mother is going to be fine,” the nurse says. I breathe more easily, in, out, in. The word settles into my stomach.

Fine

. Was she fine before?

The nurse looks at her clipboard to make sure she has my relationship to the patient right. I nod at her that she does. She tells me we've been lucky; my mother's just going to need to stay in the hospital for a little while.

Lucky.

It doesn't seem like the right word. Still, a few of the knots in my stomach unravel.

Then they come back when I think about how much it will cost for my mother to stay in the hospital.

And when I open my mouth and move my lips, no sound comes out.

“Would you like us to call someone for you?” the nurse asks again. “Your mother can't receive visitors yet, and you might be more comfortable at home. We can make a call if you need your dad or someone else to pick you up.” Her words are efficient, routine, but her eyes are soft. Does she make this offer to everyone, or is she making an exception for me?

I shake my head. Then I finally get some words out.

“No, thank you.” The words are froggy, like I've gone longer than just the past hour without speaking. She can't call my dad because I have no idea who he is. Someone else? I remember my mother reciting instructions to me; me, at eleven, nodding solemnly.

If anything ever happens to me, Sophieâ¦

I know where I have to go next. But I'd rather put off that phone call as long as possible.

I get up slowly, my jeans stuck to the backs of my legs. My bright blue backpack is still here, sitting on the chair next to me, and it makes me think of a puppy, loyally following me everywhere. My mother and I found it in a bin at a discount outlet store, and it has one badly sewn seam and someone else's initialsâ

JKP

âacross the front. I sling it on, letting the weight of homework and textbooks settle onto my shoulders. I thank the nurse again and follow the exit signs out of the hospital. As I walk home, JKP's bag bounces against my back, keeping me company.

Three

By the time I'm back on the top floor of our apartment complex, clicking the key into the lock, I've made a mental list of everything I need to do next. Wash the dirty coffee cups and take out the trash. Offer one of the neighbors any food from our fridge that might go bad. Tell the post office to hold our mail.

Pack two bags. One for my mother, one for me.

Clean up the pills on my mother's bedside table.

The first few chores are the same ones I do every day, and I start them mechanically, soaping the lime green sponge next to the sink and cleaning a plate, then letting the suds sit in last week's coffee mugs while I vacuum up the shredded catalog pieces from the front hall.

I'm so lost in my routine that I take a package of ground beef out of the fridge and unwrap it, preparing to make dinner. I do thisâmake dinnerâevery night. Every normal night. Now, as I stand in the empty kitchen with the light off, one hand holding a clump of ground beef, the memory of those nights drifts toward me through the dark.

â

My mother came into the kitchen when I was halfway through shaping the beef into patties, my hands goopy over the sink. She half danced, half walked into the room and dropped into a chair.

“Homework done?” she asked. I shrugged, but she didn't notice, already on her next thought. “Of course you've finished your homework already. Why do I even ask that anymore? It's always done.”

I grinned at her over my shoulder. My mother assumed my work was done because I was a good student. I never told her it was because homework was the easiest part of my day, the only thing I could dash through without caring how it turned out.

I heard her hop up from the chair and start moving again, probably twirling around the table with her hair whipping out behind her. Even in her worn painting pants and baggy sweater, she moved like she was wearing floaty summer skirts.

“Good painting?” I asked without turning away from the counter. I reached up to the cabinet for garlic powder and salt. I hesitated, looking over the rest of the spices, then grabbed the chili powder too.

“Hmm,” my mother said. It was her usual answer, noncommittal, but I liked to think it meant she'd had a good day in her studio. I pictured her down there, arms flying, music playing, the old cushion on the floor in the corner where I would sit and draw while she worked.

Here, in the kitchen, she walk-danced closer to me. “What's for dinner, Sophie?” Her tone was teasing, like she knew what we were having but wanted to make me say it, like it was the setup for a joke.

“Burgers.”

“Burgers,

again

?” She tried to sound fed up, but she couldn't quite keep the smile out of her voice.

“Yes, burgers

again

,” I said. But I couldn't keep a straight face either. I dropped the patty I was holding and reached toward my mother. She skipped out of the way, laughing, before my goopy fingers could grab her. I laughed too. I put my elbow down on the counter so I wouldn't lose my balance. Then I waved the chili powder at her, to show they wouldn't be exactly the same burgers as usual. I flicked the cap open and started to sprinkle the spice on the patty in a swirly pattern.

My mother stopped in front of the fridge, which hummed and thunked like it was part of our game. I covered a plate with a paper towel and set the burgers down. But before I could heat up the pan, my mother opened the freezer.

“Don't do that just yet,” came her voice from behind the door. Ice-cold air wafted into the room. I turned to face my mother's voice and saw the bright orange streak across the white freezer. It began as a handprint and trailed off into a smear. My fault, an accident when we repainted the kitchen walls last year. I had started to wash it off right away, but my mother stopped me.

“It's like something you would have done when you were little, finger-painting with your friends,” she'd said. “Let's keep it.”

I'd wanted to ask

what friends?

I'd pictured Leila and James. Their tinier, rounder-cheeked kid faces, the way they were in our finger-painting days, not the way they looked now when I passed them in the halls at school, as they moved in groups of friends and I walked by myself. I'd winced, thinking of them. But I had stopped scraping the paint away.

My mother had told me it looked cheerful in the kitchen light, like a spark.

“Why shouldn't I finish the burgers?” I asked the part of my mother I could see below the freezer door. I was playing along; I already had a good idea why my mother didn't want me to cook dinner yet. I turned on the tap with my arm so I could wash the gunk off my hands.

“Close your eyes,” she said. I did, and I heard something thud onto the counter, then the softer sounds of plastic containers landing next to it, then a few glassy ringing noises and metallic clanks.

“Now open.”

I wasn't surprised by what I saw, but I gasped and dropped my jaw anyway, and my mother's laugh bubbled up from her stomach. She looked like she wanted to clap her hands, so delighted I giggled too. On the counter, two bowls, two spoons, a carton of ice cream and an ice cream scoop, sprinkles, and a squeeze-top bottle of chocolate sauce. The ice cream was cookie dough, our favorite flavor.

“Dessert first!” my mother said. She sent a bowl across the counter to me with one hand, like a Frisbee, and flipped the lid off the ice cream carton with the other. Still laughing, we dug in.

â

I blink and realize I'm standing in a dim kitchen with a fistful of ground beef. I'm squeezing it so tightly juice is dripping down into the sink. I look behind me out of habit, but of course my mother isn't here, and tonight I don't need to make dinner. Without the lights on in the kitchen, the orange paint on the freezer door is just a dull streak, ugly, not little kid cute.

What am I doing?

I toss the beef in the garbage and think about the things still left on my list. Take out the trash.

Clean up the pills.

Pack the bags.

Go.