Thirty Rooms To Hide In (6 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

This is how it was. She did, however, have one room where she could hide.

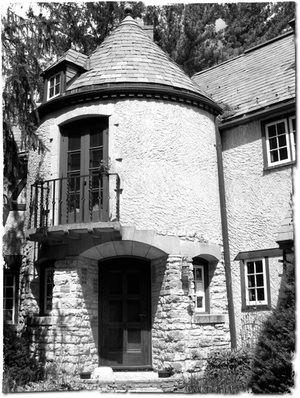

Above the main entryway of the Millstone, the balcony to Mom’s library; above that, the conical roof of the attic.

Long before schools installed public address systems, there was the booming and benevolent basso profundo of Rubert James Longstreet – my mother’s father and principal of Seabreeze High School in Daytona Beach, Florida.

Grandpa RJL began his career in education as a teacher but his final post was 30 years as principal of Seabreeze, where my mother graduated in 1941

as its valedictorian. RJL retired in ‘49 and though his beloved high school was demolished in the late ‘50s, an elementary school in Daytona Beach stands today bearing the name: “R. J. Longstreet Elementary School.”

RJL had a classicist’s love of knowledge and to the very end of his days continued to learn, study, read, and teach. He retired in the small town of DeLand nearby but continued as a professor of law at Stetson University. Just outside town in a little home on Lake Winnemissett, he kept a library of 2,000 books – on ornithology, history, religion, science, and philosophy. On clear nights he fiddled with his new telescope to look at the moons of Jupiter and during the day continued to band birds to study their migrations.

He was thrilled when told a pelican he’d banded as a young Audubon Society member in 1933 was retaken 31 years later a hundred miles to the north.

His love of knowledge, of books, and of learning was thoroughly transferred to his daughter. And though she was every bit the lifelong student her father was, she’d occasionally confess – even late in her life – that she felt “uneducated.” Tuberculosis and marriage had disrupted her college career and lacking the actual certificate she felt her lifelong studies somehow didn’t count. But she had an extraordinary education – self-made – one that began during her convalescences and continued throughout her life. As a reader, she was tireless. She ate information. She tore through books at a pace that would’ve made Evelyn Wood the speed-reading queen just slam her book down and say, “Myra, can we just take a fucking

break?”

She was never without a book. She grabbed one on the way to the hospital to have a baby. She had one in the car “for emergencies.” She read while stirring Sani-Flush in the Millstone’s toilets and while waiting to pick up her boys from school. If she didn’t have a good book to read, she’d head to the library at night, even during a Minnesota winter.

Her education did not cost us a parent; she was a mother first, a student second. She read in stolen moments; in between breaking up fights or hosing our art off the walls. Throughout the house she kept books propped open to be read while she ironed or cooked or sewed. Taped to the refrigerator were definitions of new words to learn; to the front door, new titles to get at the library. She brought home children’s books too and left them by our bedsides, in the basement play room, on the porch, even on a reading rack in the bathtub. Her education suffused the whole house with the rustle of a university library – the turning pages of six boys reading books, the older ones writing in their journals.

And then there was her crown jewel – the Tower Library.

“Tower” makes it sound higher than it was; it was only the second floor. But it was the way the room commanded that whole rounded section of the Millstone – above the curved stone entryway and below the cone of the attic’s red-slate roof – that gave it the feeling of a tower.

French doors opened onto a small stone balcony and let morning light into the small oval room. It was here where my mother’s love of learning flowered.

Myra believed, as her father did, that “books are the best wallpaper.” So she began to paper the room, filling the shelves as her interests grew and took turns like a river, branching from philosophy to history, the Revolution to the Civil War, biography, astronomy – everything but “popular novels,” which both she and her father disdained. Even the library’s ceiling bore the imprint of her interests – there she carefully mapped out the constellations in pencil and labeled the stars.

In the middle of this room was her favorite place to write, an antique Betsy Ross desk; with drawers on both sides, it was a desk made to own the center of a room. In its drawers she stored the letters from her father and at this desk she answered them.

Their letters were written on the small blue composition notebooks, the same kind the old professor handed out in his classes before essay tests. They called their letters “Blue Books” and when a year’s worth of them had collected on his desk in Florida and hers in Minnesota, Grandpa would gather and bind them by hand in green hardcover books. The complete set of their correspondence now stretches across 37 inches of my shelf.

By the time our family moved into the Millstone, Myra and RJL were into their tenth year of weekly correspondence and subjects were well established. Family was first. But the letters were more than “the kids are fine.” The two of them filled the Blue Books with such detail about their daily lives that even if long-distance telephone had been affordable, the sheer volume of information they exchanged would have moved through the wire like a goat through a python.

Following family life and daily events, the subject was books; old books, in particular. The smell of old books, the delicious weight of them in one’s hands, and the musings on who the previous owners might have been. History, biography, and literature formed the core of their interests, but they also studied Greek together, the daughter sending her weekly translations 1,500 miles to the professor with a 3-cent stamp.

As the ‘60s brought the nation’s attention to space flight, the two of them studied astronomy to complement their breathless viewings of every lift-off from Shepard to Armstrong. The new decade also brought the centennial of the Civil War and the two of them inhaled volumes on the great conflict. R.J. Longstreet and daughter were related to Confederate General James Longstreet (cousin, several times removed) and although Myra and the professor were both card-carrying liberal Democrats, their sympathies leaned to at least one Confederate, the often-maligned soldier who Robert E. Lee called his “Old War Horse.”

RJL, in a letter to Myra:

Am moving along through Catton’s This Hallowed Ground and the next few pages will have me back in Gettysburg. Shall be interested to see whether General Longstreet gets the blame again for not taking Little Round Top. Some day I want you to stand with me on that summit. Let’s spend at least two or three days immersed there in our favorite subject before it is too late.

The comforting smell of old books and the silence of Mom’s library seemed to me an ideal place to set up my army men and conduct noisy large-scale wars. More than once, her prized editions on the Civil War served as fort walls, behind which I set up a motley band of soldiers, mixing cowboys and Indians, World War II soldiers, and the Blue and Gray. Like General Longstreet, I too sent my captured prisoners south – down the laundry chute to the distant basement.

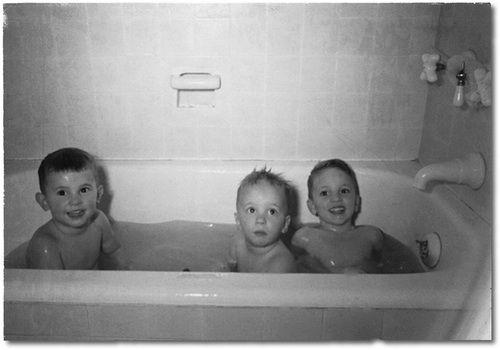

Dan, Luke and Chris, circa 1956.

The Civil War was not my introduction to the whole idea of “sides” –

that

had been formed by fighting with my brothers. But the whole idea that grown-ups had once broken off into warring groups so clearly defined they even had uniforms, well, this was fascinating; conflict institutionalized. On top of that, these guys had

forts

. And forts were cool.

My very first forts were sculpted on my mother’s dinner china. Fort Mashed Potatoes was indeed a mighty structure, its high ground commanding the entire plate. Bristling with baby-carrot cannons and staffed by green-pea Army Guys, it was impregnable to all but the Giant Fork. (Fort Au Gratin, by the way? A total bust.)

Little boys who lived in the quiet Midwest of the 1950s were, of course, under constant attack by armed hordes and so forts had to be constructed everywhere. A ring of pillows in your bed. A blanket over a card table. And no matter where the fort went up, that outer wall was key – it separated Them from Us. Inside the wall you had sovereignty. A room to hide in and outlast any siege (provided you’d put up enough Kool-Aid and Hostess Sno-Balls).

Along with the idea of forts, the Civil War introduced serious weaponry. Did cowboys and Indians have artillery? We think not. Bayonets? Please. The

Monitor

and

Merrimac

? No and no. The Old West’s dusty little skirmishes and scalpings were playpen fights we thought, compared to battles big enough to have names.

In a letter to RJL, Mom wrote about my nascent interest in the Great Rebellion:

In Luke’s kindergarten class, we divided the children – three into the Northern group and two for the South. Luke Longstreet was tickled to be General Longstreet, saying “That really is me.” I made battle flags for Chancellorsville, Manassas, and Fredericksburg. But history dealt a hard blow to Luke and General Lee. They couldn’t understand how they could win so many battles and yet lose the war. Luke said, “Let’s do it over again next week and this time we win.”

Seeing my interest in the Civil War, my mother poured in as much history as my little teacup would hold, but I was in it for the blood. Winning was everything. One side had to lose. Or more precisely, one side had to be “The Loser.” In a just world, right beat wrong like rock beats scissors and not being on the winning side set one’s whole world crooked. Not winning an argument, unthinkable. Not winning a game of Civil War (or “Army Guys” as it came to be known), that was catastrophic. Perhaps worst of all was being shot by a soldier you had

already killed.

This was injustice itself.

In fact, the issue of authenticating death in all games of Army Guys was a sticky wicket given our ordnance was invisible bullets fired from imaginary guns.

“You can’t shoot me! You’re already dead!”

“I was just wounded! You’re the one who’s dead!”

“How can I be dead? I didn’t fall

down

.”

Everyone knew that proper machine gun deaths were officially identified by a herky-jerk marionette dance and a full face-plant in the turf; this was agreed-upon play action. Our backyard version of the Geneva Accords required adherence this agreement otherwise, what did you have? A universe without rules, where any fool could just jay-walk through your hailstorm of hot lead? Unchallenged, such heresies lead to anarchy, as it did on occasion when someone would secretly switch from Army Guy rules to Super-Hero rules.

(“The bullets bounced

off

me so I’m not dead.”)

This kind of nonsense was shut down on the spot.

Army Guy rules were fairly specific, one of which required you to produce a realistic machine gun noise. In fact, having the best rat-a-tat-tat was another thing your side could win at. Individual bragging rights, however, went to the guy with the most realistic noise, a sound we each created with various success behind a spitty mist of grape-colored Kool-Aid.

If you were out in the open and you heard the ack-ack-ack, you were dead. Since losing was unacceptable, you made your peace with being killed by winning in the Best Death category. Nobody died as good as you. You flung yourself to the ground, overacting a death rattle that could be heard from the cheap seats, giving your first-grader’s take on the Greek playwright’s timeless “Oh verily, I am slain!” Your hands went to stomach, your legs crumpled and then stillness. Of course, death by grenade was even showier – the concussion flung you several feet to a boneless rag-doll heap of heroism. Tossing grenades was also a show because you had to pull out the arming pin with a manly yank of clinched teeth. The one drawback to grenades was your opponent needed to actually see you throw it, otherwise your dramatics were for naught and after several moments of silence on the battlefield you had to verbally inform your enemy of his demise.

(“Hey, I tossed a grenade in there, you know.”)

Falling to the spongy green grass, that was death for us – your face to the Minnesota sky, the sunlight turning eyelid blood vessels into orange spider-webs.

There you lay, certain your showy death had given a sort of murderer’s remorse to your assailant, and you waited until the battle ended or Mom called you in for sandwiches.

To us, that’s all death was – a brief midsummer stillness and then a sandwich.

Real death didn’t exist yet. It certainly hadn’t happened to anyone we knew; our grandparents were alive, our parents, even the family dog. Of course, we’d heard stories about Heaven during our few visits to Sunday School, but Heaven sounded like a cartoon – angel wings, halos, and harps and a bunch of other silly shit even we little ones didn’t buy. Still, the grown-ups seemed convinced and from their description Heaven was basically an existential do-over.

Death, too, was a cartoon. When you fell off a cliff like Wile E. Coyote, you didn’t die – you became accordion-shaped. Even on the grown-up’s TV programs, death was a pratfall. Shoot the bad guy on Sunday night’s

Bonanza

and there was no blood, just a crumple to the ground followed by

Bonanza’s

theme song and the credits rolling by.

We never gave Death or Heaven a second thought, but those ending credits on

Bonanza?

They were horrifying. Because Sunday was a school night, school nights meant bedtime, and to little boys bedtime was in fact Death.

Bedtime was the sudden, unexpected, and horrifying end of all things. Even though it came at precisely the same time every night, even though we received count-down warnings as the dreaded hour approached, when it arrived we never failed to be both shocked and aghast.

(“WHAT?? But we’re not even tired!!”)

Bedtime was so much like death we went through the same Kübler-Ross stages of acceptance.

Denial –

“It CAN’T be bedtime.”

Anger –

“Why do we even HAVE bedtime?”

Bargaining –

“If you let us stay up, we’ll go to bed tomorrow after lunch.”

Depression –

“This is the worst thing that has happened since the dinosaurs.”

And finally, acceptance.

Bedtime was indeed death. Even the rituals were the same: the preparing of the body (the solemn washing of teeth, the funereal donning of pajamas), the readings, the occasional prayer, and finally the inevitable darkness. All that was missing were Hallmark sympathy cards arriving in the mail:

Our thoughts are with you during this difficult hour, when “Bonanza” is over at 8 pm Central Standard Time, and 9 pm Eastern.

Aside from the nightly horror of bedtime, the days of the early 1960s brought little that was truly life-threatening. There was no terrorism on the nightly news, no anthrax, no AIDS; no buildings falling, no children disappearing. There was only the sunny back yard with games of Army Guys and Mom’s sandwiches and the grass unreeling under your feet as you ran and ran and never grew tired.

Wait. There may have been one thing – Being In Trouble. That was scary. And you knew you were in trouble when Mom changed your name to “Young Man.”

“And just what do you think you’re doing, young man?”

That was bad, but Mom’s punishments were swift and fair. Far worse was Being In Trouble with Dad.

Convicted murderers await execution at midnight but you, Young Man, your hour of reckoning was always “When Your Father Gets Home.” You had to wait. Since this was before you knew how to tell time, the hour of When-Your-Father-Gets-Home ’o’ Clock arrived when it arrived, with only the warning crunch of gravel in the driveway as his car pulled in. You ran upstairs to watch unseen from a high window as Dad entered the Millstone. You caught some of the muffled conversation down in the kitchen, certain you’d heard the phrase “limb from limb,” and then listened for the inevitable thump of feet on the stairs. When at last the door to your room opened, there was nowhere left to hide but the fort inside your head. Dad’s red face bent down within inches of yours and then came the huge wads of angry sound you could almost hear with your hair. With his spittle misting your black-framed 1960’s glasses, the Alamo inside was as far away as you could get and it’s there you waited for the final whack on the back of your head.

It wasn’t particularly painful, the whack – just humiliating. It always came, and always with its signature phrase: “WHAT DO I HAVE TO DO AROUND HERE?? KNOCK SOME HEADS TOGETHER??”

In the early days, that was the closest we Little Ones got to the furnace of Dad’s anger, its orange flames not yet white with rage.