Think Like an Egyptian (10 page)

Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

16.

SICKLE

Egyptians mainly grew cereal of two kinds: emmer wheat—which does not thresh easily and has tough, spiky heads—and barley. We know from tomb scenes of the harvest that the ears and heads of the cereal were cut quite high, leaving much of the straw standing. The cutting was done by a curved wooden sickle that sported a line of serrated flint blades on the inside edge. Flint was used for perhaps 3,000 years after the introduction of copper and bronze for other kinds of cutting edges and illustrates how, in traditional societies, individual technologies can keep going as an independent tradition if they satisfy the user.

Once gathered, the ears of emmer wheat and barley were hauled off the fields in large baskets, sometimes slung over the backs of donkeys. Their destination was a piece of hard, dry, and clean ground set aside for threshing and winnowing. Here the cereals were spread out in a layer. Hoofed animals were driven back and forth across them to separate the ears from the heads. The chaff and dust were separated by men repeatedly tossing the trodden grain into the air using a pair of wooden scoops, to allow the breeze to carry away the lighter unwanted elements. The cleaned grain was scooped into containers and heaped onto a prepared mud surface with a raised rim. Scribes, ever disdainful of manual labor, counted the scoops (which had a fixed capacity) and so measured the harvest.

17.

GRAIN PILE

Full granaries were a source of great satisfaction. It was, however, the heap of measured grain standing on a low mud platform beside the threshing floor that more readily symbolized the successful harvest and gave rise to a hieroglyph. Behind the successful harvest, and in contrast to the simplicity of the technology, lay a complex system of land management. Much of the land seems not to have been in the hands of farmers at all, but owned by temples and members of the governing class (including the royal family). They, in turn, rented out large parts of the grain lands to others, who might then employ lesser people to do the work. Even the extent to which farms existed, in the form of discrete areas of land with one owner, with a farmhouse in the middle, is far from clear. When we do have more detail, estates, especially those belonging to temples, seem to be made up of plots of land in different parts of the country, the accumulated result of centuries of buying and selling, of subdivided inheritance and of gifts and rewards.

Much depended upon the reliability of agents paid to manage the estates, whose owners would often have been busy, and distant officials. And so Egypt, like other similar ancient societies, developed systems of bureaucratic checking. Egypt was a very controlled society. No one, high or low, was ever very far from someone else’s paperwork. One inevitable consequence was the deadly game played by those who cheated the system, and those paid to check and investigate. A long indictment has survived, from the reign of Rameses IV (1153-1147 BC), against a priest in the temple at Elephantine. Accusations of violence, impiety, and seduction are followed by details of a major scheme, running for several years, in which boatloads of grain destined for the temple granaries were stolen. This must have involved the tacit assent of many people and is a fine example of a “black economy” at work. The evidence gathered was specific: someone had done a thorough investigation and was able to cite, year by year, the exact deficit of grain sacks. What the outcome was we will never know, but death for the main culprit is very likely, and perhaps mutilations for others.

18.

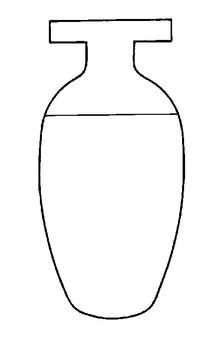

BEER JUG

Stored grain was wealth, and sacks of it were used as a medium of exchange, in effect as a form of money. It had, of course, a limited life in store and so could not be hoarded for too long. The constant emptying of the granaries kept wealth in circulation, never earning interest, and provided a healthy local economic stimulus. In the end, however, apart from what was set aside for next year’s seed, grain was consumed, and thus it formed the principal element in the Egyptian diet. It was eaten in a wide range of baked products—breads, cakes, and biscuits—and fermented into beer. Many records have survived of ration payments issued to employees, and even workers at the king’s court, and they consist of so many loaves of bread and pottery jugs of beer. In one tale an unusually eloquent countryman is detained at court so that the king can secretly enjoy the countryman’s well-turned speeches of complaint about injustice to the poor, and in return the king supplies him with a daily ration of ten loaves and two jugs of beer, and sends his distant family three sacks of grain every day.

Modern research has tried to work out how ancient Egyptian beer was made. The process is depicted in tomb scenes, and much can be learned through the microscopic study of beer residues inside pottery vessels used in the brewing process. What was once regarded as a rather crude process is now understood to have been more sophisticated and would have allowed the brewer to control the taste of the final product. It relied upon malting (allowing the grains to begin to sprout and so release their sugar) and, crucially, the mixing and blending of uncooked malt with cooked grain or malt. What we cannot today discover, unfortunately, is the taste. Most modern beers of the European tradition have the strong bitter flavor of added hops, but this plant was unknown in ancient Egypt. Other plant flavorings might have been added, such as coriander, but it has not yet been possible to detect them scientifically.

Drunkenness was a yardstick of pleasure: “If I kiss her, and her lips are open, I am happy, even without beer” is a verse from a love poem of the New Kingdom. Beer was enjoyed at festivals, and days off for brewing are one cause of absenteeism in work registers of necropolis workmen of Thebes. The feasts of the goddess Hathor seem to have been a particularly appropriate time for drinking to excess. “Come, walk in the place of drunkenness, that pillared hall of diversion,” invites a song to Hathor, “Drunkards serenade you by night.” One myth explains the connection. “Mankind” (i.e., the Egyptian people) rebel against the aging sun-god Ra. They flee from his wrath into the desert where they are pursued to destruction by Hathor, now no longer kindly but an avenging goddess whose lust for blood is assuaged by red-pigmented beer being poured over the fields as if it were an inundation of the Nile.

19.

BULL

Perhaps on account of their size and natural dignity, the Egyptians saw cattle as, to some small degree, proximate to themselves. An Egyptian term for mankind was “the cattle of god,” and conversely the term “herdsman of mankind” described the kindly role of the king and of the creator-god. In ancient times, cattle still existed in the wild, and the fierceness of wild bulls provided a suitable image of the king, who terrifies on the battlefield. “Victorious bull,” using a more aggressively posed hieroglyphic sign,

, was a standard epithet for the king. More prosaically, the same names were used for some of the body parts of humans and of cattle, such as “ribs” and “liver.”

, was a standard epithet for the king. More prosaically, the same names were used for some of the body parts of humans and of cattle, such as “ribs” and “liver.”

, was a standard epithet for the king. More prosaically, the same names were used for some of the body parts of humans and of cattle, such as “ribs” and “liver.”

, was a standard epithet for the king. More prosaically, the same names were used for some of the body parts of humans and of cattle, such as “ribs” and “liver.”Cattle were both worthy of reverence and were a practical food resource. The earliest example of a sacred animal cult is that of the Apis bull. Centered at Memphis, ancient annals as early as the 1st Dynasty (c. 3000 BC) record a “running of the Apis bull.” There was only ever one Apis at a time, and in the later New Kingdom and onward until Roman times each Apis was, on death, given an expensive burial in an underground catacomb, the Serapeum.

A second cult of a sacred bull, that of Mnevis at Heliopolis across the river from Memphis, went back at least as far as the 12th Dynasty. Certain other gods drew upon animals for their appearance: the ram or ram-headed god Khnum at Elephantine is one example; the crocodile or crocodile-headed god Sebek at Kom Ombo is another. For much of Egyptian history, however, we have no knowledge that living specimens were regarded as sacred: this came during the last seven centuries or so of Egyptian civilization. Sacred animal cults then became hugely popular, and living representatives of a whole species were viewed as sacred. As a result everywhere in Egypt cemeteries appeared of mummified animals—cats, baboons, ibises, fish—sometimes in catacombs that held millions of carefully wrapped specimens.

This is not a sign, however, that the Egyptians held wildlife in special reverence. They were not vegetarians. Hunting wild animals in the desert was a sport for the king and his nobility. King Amenhetep III issued two sets of large scarabs to commemorate his hunting success, in one case against desert lions (102 kills in ten years) and in the other against wild bulls (96 in two days). It seems unlikely that the deserts adjacent to Egypt even at this time supported wildlife in these numbers, and animals for the hunt may have been imported from much farther to the south. Domesticated cattle was an important source of food, and prime cuts were prominent among food offerings at temples. Some temples possessed an actual slaughterhouse or slaughter-court as part of their layout. Perhaps the most striking example of acquiescence to the deaths of animals otherwise seen as god’s creatures occurs at the Aten temples of King Akhenaten. Despite the pious sentiments of hymns to the sun-god, the cult of the Aten demanded the presentation of food offerings on a large scale, and so the main Aten temple was provided with a butcher’s yard, and the high priest Panehsy also held the office of “overseer of the cattle of the Aten.”

Other books

Fat land : how Americans became the fattest people in the world by Crister, Greg

The Deadly Conch by Mahtab Narsimhan

Common Enemy by Sandra Dailey

Spellcaster (Spellcaster #1) by Claudia Gray

The Haunting of Gillespie House by Darcy Coates

Return of the Viscount by Gayle Callen

Boss Life by Paul Downs

Sins of a Shaker Summer by Deborah Woodworth

Forbidden To Love (The Erosians) by Wills, D

Trollhunters by Guillermo Del Toro, Daniel Kraus