They Spread Their Wings (2 page)

Read They Spread Their Wings Online

Authors: Alastair Goodrum

Later, he wrote again:

Yesterday I was vaccinated, inoculated for typhoid and tetanus and had a whole lot of blood taken to find my group. All this took precisely five minutes! Now we have got such stiff arms we can hardly get dressed. I have got a uniform but as no single part fitted, it has gone to be altered so I am back in ordinary clothes again. We are only issued with two pairs of socks so if you want to start knitting you can start with socks. Apparently, although they tell you that you only stay here for a few days it is most likely you stay for a month. I will probably leave on January 18 … possibly to go to Scarborough … a new training place. The beds are frightfully hard. We are up at 06.30, breakfast at 07.15, lunch at 12.30, tea at 16.30. The food is not too bad but I go out every night and get some sort of a meal because the only dinner provided is a mug of soup and dry bread. The canteen is very bad and miles away from here, so we don’t go to it.

There was little respite when his posting came to No 10 ITW at Scarborough, where he arrived on 5 January 1941 in 4in of snow and freezing weather. Howard was placed in No 1 Flight of No 3 Squadron and accommodated in the Crown Hotel. By the end of that month he was coping with the theoretical instructional courses and doing well in maths (‘passed maths with 87%; … morse code 94%’) and navigation. The food was still lousy and he and his compatriots took extra meals at a nearby hotel. His spirits were raised, however, when he was issued with a white band to put round his forage cap, which signified an airman under aircrew training. ‘This makes us a bit different from the ordinary AC2s,’ he wrote.

As a growing, energetic lad the subject of food always loomed large and on 24 February 1941 he wrote:

The food does not improve and you can’t buy any fruit in Scarborough for love nor money. The pork pie was jolly good thanks and so were the sweets. As we don’t get off ‘till 19.00 it’s very difficult to get anything because the shops are shut. Everyone has to go out at night and get some more food from somewhere. The best canteen is the Salvation Army, it’s better than the YMCA and the ordinary canteens. The socks are lovely. They have got some heat on in this place now … and the mattresses arrived on Thursday so we can sleep at nights now.

During February, Howard spoke of the next stages of training, telling his parents:

I think we are almost sure to get sent abroad for flying training, as they are now needing more and more aerodromes in England for active service aerodromes as the number of aircraft in the country is increasing so rapidly. Actually, the squadrons who are a week in front of us in this course, have already been asked to volunteer for training either in Canada or South Africa. I think I shall volunteer for Canada if I get the chance.

In the event, Howard was stuck in Scarborough until the end of April, the reason probably due to delays in the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) training programme caused by lots of bad weather earlier in the year. A letter dated 6 May 1941 locates him in Wilmslow at a despatch centre waiting to be posted abroad. He travelled that night to Scotland for embarkation but due to enemy air raids had to spend three nights in Kilmarnock, sleeping on the floor of the Town Hall, before he could board ship and sail from the Clyde on 10 May 1941. The next time the family heard from him was via a cablegram dated 22 May, saying he had arrived safely in Canada.

True to form, it was not long before a letter arrived at the family home. On 25 May Howard brought the family up to date:

It was good food on the ship. Masses of cigarettes at 1/6 [one shilling and sixpence] for sixty – they are duty free you see. I arrived in Toronto on 24 May and it was a thirty hour train journey from Halifax [in Nova Scotia], via Montreal. We expect to stay ten to fourteen days here. Billeted in the Exhibition Grounds, waiting to be posted to an Elementary Flying Training School near here. You’ve no idea what it is like out here – no blackout or rationing or anything, it’s really marvellous to see all the lights again. The Canadians are awfully good to us; treat us like guests, make us feel very welcome. Everybody out here almost lives on Coca Cola and ice cream sodas and various milk shake concoctions. All these are iced and are jolly good. Everything out here is iced! I have gone halves with another fellow who came out with me and we have bought a car for the equivalent of about £10. There is a big fun fair by the lake – like Blackpool – and Niagara Falls is only eighty miles from here. I am looking forward to starting flying very much indeed.

Howard had reached No 1 Manning Pool/Depot RCAF, located in the Coliseum part of the impressive Toronto Exhibition Grounds. Here he would become just one more anonymous airman among the thousands of trainees being split up and despatched to the plethora of flying training stations throughout Canada.

Events now moved apace. Howard left Toronto on 27 May and arrived at No 1 EFTS at a place called Malton, Ontario, and he told his parents he was now a Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and learning to fly the de Havilland Tiger Moth. Less than two weeks later he wrote again, telling them proudly: ‘I have been doing quite a lot of flying and I went solo yesterday [5 June 1941] for the first time.’ And a week later: ‘I have been going solo quite a lot since my first one. Have done about 750 miles in the car – no gas [petrol] rationing.’

At the end of June he wrote:

I am getting along OK with flying. I’ve got forty hours in now, twenty of them solo. This course finishes in a fortnight. It’s still hot here and I fly in my shirt sleeves and you have to go up to 7,000 or 8,000 feet to keep cool even in an open cockpit.

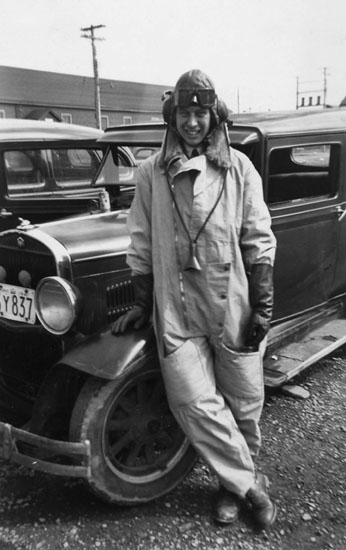

Pilot under training Howard Clark with his car, at No 1 EFTS in Malton, Canada, May 1941. (Clark Collection)

Howard was coming to a crucial period. The end of the course was looming and on 7 July the time for exams arrived. He was confident he would do well and expected to leave Malton mid-month for his next posting, a Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where he would fly the twin-engine Avro Anson. After a forty-eight-hour pass he reported for duty at No 5 SFTS at Brantford aerodrome, about 45 miles from Toronto. He said: ‘I’m flying Ansons now. They are really rather nice. I thought I would not like them much after the Tiger Moth but I have changed my mind, although they seem rather like driving an old ten-ton lorry after a sports car.’ By the end of August Howard moved on to the senior course. Having completed all his night and cross-country flying exercises, and with eighty-five hours in Ansons and sixty-five in Tiger Moths, he was about to be awarded the coveted ‘Wings’. That eagerly awaited event arrived in the form of a parade at Brantford on 22 September 1941 and on 4 October he cabled his parents to tell them he had been commissioned and was now 109112 Pilot Officer Howard Clark.

At this juncture there is a break in correspondence, but the next letter shows that much had taken place in the meantime; he wrote it on 8 December 1941 from the officers’ mess of No 52 Operational Training Unit (52 OTU) RAF Aston Down, near Cirencester in Gloucestershire – a Spitfire OTU. He was back in England and had at last achieved his dream of becoming a fighter pilot.

By building up his hours on the Spitfire during the month, Howard seems to have gained experience and confidence to such an extent that in January 1942 he was asked to remain as an instructor for two more months. While disappointed not to be going to a squadron, he nevertheless relished the prospect of putting in more hours in the Spitfire and felt it should give him a better chance of being posted into action with a ‘crack’ fighter squadron. After a few days’ leave this chance seemed to materialise when, on 15 March 1942, he wrote to his parents from RAF Blackpool, No 4 Personnel Despatch Centre, where he was waiting to go overseas, to say he had been posted to the ‘Middle East Pool’ in Egypt. He was destined to twiddle his thumbs – a situation he described as ‘stooging’ – in Blackpool until 21 March:

Sat 21/3 Left Blackpool at 8.30pm for Greenock – all night travelling. Bloody awful. Very cold, bloody draughty carriage. Soon ate all the food provided. 1/6-worth of bully beef sandwiches. Sun 22/3 Arrived Gourock 9am. Wrong place. Eventually arrived Greenock at 10.30am. Embarked on SS

Alcantara

[22,000 tons]. Pretty bloody boat. B-awful cabins.

This former cruise-ship-turned-trooper sailed at midnight on 23 March to join a convoy off Ireland for the run down to Freetown, capital and principal port of Sierra Leone in West Africa. Their southerly progress was most visibly marked by the gradual increase in temperature and Howard was in shirt and shorts and complaining about the heat by the time the ship tied up in Freetown on 6 April. His patience was tested still further when, the next day, he and his travelling companions left the

Alcantara

to embark on the SS

New Northland

(3,400 tons) – a tramp steamer that would make the

Alcantara

seem positively luxurious:

Loading cargo and taking on native troops. The boat is B----- awful, we are all very, very browned off, still on this B-----

Altmark

[a pointed reference to the captured German prison ship] it is full of cockroaches and beetles, water supply only on for one hour a day. Found a mosquito in my porridge at breakfast. We keep being told we are sailing tomorrow, always tomorrow.

His feelings were summed up in a note, written on the back cover of his diary: ‘FREETOWN IS THE A***HOLE OF THE WORLD.’ The ship sailed on 15 April for the port of Takoradi in the Gold Coast (now Ghana), escorted by one corvette. By the 19th it was even hotter and the bar had run dry. The

New Northland

docked in Takoradi on 19 April and Howard was able to slake his thirst for a beer during a run ashore. Upon his return he discovered that his party was to remain on board and sail the next day to Lagos in Nigeria, which was reached a day later. Their arrival being unexpected, they were ordered to sleep on board. ‘God, what organisation,’ wrote an exasperated Howard. However, things perked up when they vacated the

New Northland

on 23 April and were taken to the Royal Hotel and ‘had a wizard dinner’. Howard was accommodated in a villa annexe of the hotel, cooled by a breeze off the sea, with excellent food, swimming and a number of sporting clubs (such as the Apapa and Tkoya) to break the monotony of waiting for the flight to Cairo. There were 300 airmen waiting with him for a flight, but his turn came at 11.35 on 29 April and he winged his way across Africa in an American C–47 (DC–3 or Dakota).

Howard Clark’s course at No 5 SFTS Brantford, July to September 1941. Howard is seventh from the left on the front row. (Clark Collection)

Newly qualified pilot Howard Clark with an Avro Anson after his ‘Wings’ parade, No 5 SFTS Brantford, Canada. (Clark Collection)