They Spread Their Wings (15 page)

Read They Spread Their Wings Online

Authors: Alastair Goodrum

The remainder of August was spent moving the squadron to Matlaske airfield in Norfolk, from where daily readiness and convoy patrols began on the 25th. Walter, in philosophical mood, recalled:

The officers’ mess is in a delightful old watermill converted into a modern house. The stream flows underneath with lots of trout in it. It is miles from anywhere and on leaving the aerodrome there is complete peace and rusticity far away from the crowd. I have not known such peace of mind since I joined the RAF. Life is doubly enhanced when there is a danger of losing the things we like, such as the other pilots’ comradeship and the happiness of squadron life. It seems now that life is rich and full.

Back to reality, the next day saw the squadron airborne at 06.50 to fly over to Duxford for a wing briefing before the three squadrons, including Walter Dring, took off at 08.15 on a low-level sweep from Dunkirk to St Omer and Boulogne – still without provoking any enemy response. The enemy also refused the obvious invitation to come up and fight on 3 September when a Typhoon wing sweep, as top cover to Westland Whirlwinds acting as bombers, was mounted from Duxford. The Typhoons joined a Spitfire wing and swept from Nieuwpoort on a broad front down to Marck, but saw no German activity whatsoever. There was a slightly more aggressive response on the 6th when No 56 sent nine Typhoons to Thorney Island to join the wing on a sweep over Dieppe and Abbeville. Four Fw 190s dived on No 56 Squadron from above and up-sun but broke away without completing an attack. Later, off Boulogne, as the squadron was heading home, more Fw 190s approached but did not attack. The squadron landed at Snailwell to refuel then flew back to Matlaske. The enemy seemed particularly cagey about tangling with Typhoons.

Among the usual patrols and inconclusive scrambles from Matlaske, Walter Dring and Fg Off Aldwyn Rouse had a late scramble at 19.50 on the 8th, becoming airborne in a record one and a half minutes from receiving the order! They chased a Hun out over the North Sea but darkness prevented them finding it, so they returned twenty-five minutes later. Sector Ops was not happy about this early return but night-landing a Typhoon on an unlit airfield was no easy task. A few days later Walter led the dawn patrol and was taxiing along the perimeter track followed by Plt Off Myall. Juggling throttle and brakes while weaving behind that enormous engine cowling, ‘Myall taxied right up my backside,’ said Walter, ‘and his prop completely severed the rear fuselage of what was the CO’s machine, badly damaging his own aircraft in the process.’ Two more Typhoons out of action!

The squadron chalked up its first ‘kill’ with a Typhoon on 14 September 1942, when Green Section – Flt Lt Michael Ingle-Finch and Plt Off Wally Coombes – claimed a Ju 88 shot down in the sea off the north Norfolk coast. Interestingly, Wally Coombes was flying a Mk IA armed with twelve machine guns and Ingle-Finch was in a IB with four cannon.

At 13.45 the following day Walter Dring and nine other Typhoons, including the CO’s, flew down to Exeter for a 17.00 take-off on a wing sweep at 15,000ft over the Cherbourg peninsula. Once again there was no air or ground opposition and the wing returned to Warmwell for refuelling and No 56 got back to Matlaske at 19.00.

Ever since re-equipping with the Typhoon the squadron had suffered a litany of crashes in addition to the unserviceability caused by technical problems. Walter Dring added to the list on 16 September by severely damaging his aircraft during a bad landing: ‘the undercarriage collapsed and I slewed along the ground to a standstill. I sat in the cockpit wishing the earth would open up and swallow me up.’

At that date his was the eighth such accident to ‘A’ Flight aircraft and it was becoming a touchy subject among all the pilots. The situation came to a head when Gp Capt George Harvey, Coltishall station commander (Matlaske came under Coltishall control), visited the squadron on 21 September. He gathered all pilots at ‘B’ Flight dispersal to give them a stern talking-to about the numerous ‘prangs’, and according to the squadron diary: ‘meted out justice to some of the more outstanding sinners.’ By general discussion he was also trying to find out the real reasons for the mishaps and to discover a cure for them, even by improving the airfield if necessary. Walter Dring spoke up, saying he thought the chief trouble lay in the fact that when they were coming in to land, subconsciously they were all thinking they must not overshoot and several pilots agreed with him. The flight commanders, on the other hand, said they thought the problem was ‘overconfidence’.

They were now operating less as a wing. Officialdom seemed to have decided that the Typhoon was neither an effective sweeper nor fighter-vs-fighter aircraft so the Typhoon wing was in effect broken up, with squadrons such as No 56 now operating as individual units. It was around this point that the Typhoon began to be regarded as more suited to the ground attack role with an alternative role as a bomber interceptor. It was in the latter role, though, that the squadron was occupied for the most part.

The weather turned rainy towards the end of the month but there were frequent inconclusive scrambles and on 27 September Walter Dring acted as number two in a section convoy patrol with his ‘A’ Flight commander, Norwegian Capt (Flt Lt) Gunnar Piltingsrud. It was mid-October before Jerry started to come over more often, with single raiders all over Coltishall sector during the morning of the 19th. Morale flagged somewhat now that the Typhoon wing was disbanded, even though during October the squadron had thirty-five scrambles, carried out thirty-seven shipping and ‘stooge’ patrols and had started night flying training. However, on 27 October the CO received orders to start flying offensive air-to-ground and low-level air-to-air operations, called ‘Rhubarb’, so things were looking like they might hot up.

A Rhubarb was the smallest of the operations carried out by RAF fighters over France and the Low Countries. It usually required cloud cover over or near the target and could be authorised at squadron or flight level and flown by up to four aircraft, but generally these sorties were made by only two aircraft. Pilots involved could attack targets of opportunity, which meant they could pounce on just about anything that moved on land, sea or in the air, and on any building or structure that seemed to have some military importance. The first successful Rhubarb by the Typhoon pilots of No 56 Squadron was carried out on 17 November 1942.

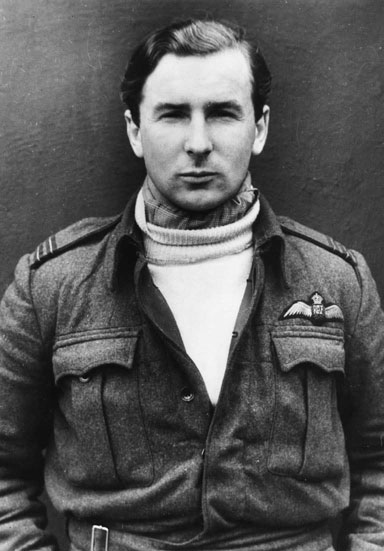

‘The Flying Farmer’, Flt Lt Walter Dring, No 183 Squadron, 1943. (John & Susan Rowe, Dring Collection)

Things were happening fast on the personnel front in November. First, on the 11th, Sqn Ldr Dundas was promoted to wing commander and posted to Duxford to command a (non-existent) wing of Typhoon bombers. Before the wing could be formed he found himself posted again, this time to a Spitfire wing in North Africa! On the 19th, Battle of Britain veteran Flt Lt Arthur (‘Gus’) Gowers DFC was promoted to squadron leader and posted away to become CO of No 183 Squadron, at that time in the process of forming as a new Typhoon bomber squadron at RAF Church Fenton. On 24 November, now with 516 hours in his logbook and once again assessed as an ‘above average’ fighter pilot, Fg Off Walter Dring started his rapid rise upwards with promotion to flight lieutenant and an appointment as a flight commander with No 183 Squadron. His promotion was duly celebrated in the mess and the next day, 25 November 1942, he prepared to take up his new responsibilities at Church Fenton and open a new chapter in his flying career.

No 183 Squadron began its Second World War life on 1 November 1942, marked by the arrival of its first aircraft, a Typhoon Mk IA, R7649, transferred from No 181 Squadron. Flt Lt Dring arrived on 30 November and new pilots began arriving from No 59 OTU. They had to wait a month before more Typhoons were slowly allotted from various sources. Mk IA, R7631 was transferred from No 181 on 1 December and the next day three Mk IBs arrived from No 13 MU: DN273, DN275 and DN297. These were soon followed by Mk IA, R7869 from No 56 Squadron and a Hurricane I, R2680 was flown in from No 32 Squadron. There now followed an intense work-up period of formation, low-flying, aerobatics, cloud-flying, air-firing, bombing and some dogfighting practices. Walter Dring became ‘B’ Flight commander and worked his new pilots hard whenever the weather allowed.

No 183 Squadron, Church Fenton, December 1942. Flt Lt Dring (middle row, third from the left), next to Act Sqn Ldr A.V. Gowers (centre). (John & Susan Rowe, Dring Collection)

It was while he was at Church Fenton that Walter met the lady who would become his wife. Section Officer Sheila Coggins was in charge of the station cipher room and, having spotted this attractive young WAAF in the foyer of the cipher office one day, Walter decided he would like to get to know her better. Sheila described how it all began:

There was a tap on the cipher office door and the same pilot appeared in the doorway. My colleague asked him what he wanted and he replied he just wanted to talk to the other cipher officer. He was told no one was allowed into the office because of the secret nature of its contents but he laughed and came in anyway. He introduced himself as: ‘String, because I am a ropey type.’ We all had a cup of coffee and biscuits and he told me all about himself. He asked me out for a meal in York and turned up at the WAAF officers mess in an old sports car and we went out and talked about each other’s troubles.

‘String’ was the nickname by which he was known among his RAF contemporaries.

* * *

More Typhoons arrived in January and February 1943, including DN242, DN249, DN253, DN257, DN271, P8944, R8884, R8885, R8886 and R8933. The actual availability of Typhoons for the practice programme during these early months was constantly diminished by the need to send all of them, in small quantities, to No 13 MU at RAF Henlow for what was said to be ‘modification’, but what this actually meant was not detailed.

Flt Lt Dring, always at the forefront of things during this intense period, suffered his fair share of problems. He was obliged to make forced landings on 27 January, due to engine failure, and on 9 February when he could only get one wheel of the undercarriage down. He pulled off a successful one-wheeled landing, but caused category ‘B’ damage to Typhoon DN297; so that was another two aircraft missing for a while. He had engine failures on 18 and 26 February, managing to land intact on both occasions, but had to belly-land when his throttle seized up on 11 March.

By 25 February 1943, equipment and organisation had settled down and the squadron was put on a ‘war footing’. For No 183 Squadron there followed a highly mobile existence, in the form of ‘exercises’ involving carefully detailed moves of the squadron’s aircraft and ground support to new locations, from where it was to launch dive-bombing ‘attacks’ against other RAF airfields. This mobility was what Walter Dring’s air war was going to be all about from now on.

It began on 1 March when a convoy of lorries set off with the ground crews and support staff from the Yorkshire base, bound for RAF Cranfield in Bedfordshire, 150 miles to the south. At 08.20 the air component of twelve Typhoons made the transit in slick formation with the CO leading. Two days were allowed for all personnel to settle in and for the pilots to familiarise themselves with maps of the area. At 07.30 on the 4th, eight Typhoons, led by the CO, were despatched to ‘attack’ RAF Chilbolton, 4 miles south-east of Andover in Hampshire, a flying distance of about 75 miles. The ‘attack’ was deemed successful and all aircraft returned to Cranfield by 08.55. At 11.55 another eight aircraft were ordered off for a dive-bombing and machine-gun attack on RAF Ibsley, 2 miles north of Ringwood, Hampshire, this time about 100 miles distant. All aircraft returned to Cranfield at 12.30, having had a grand old time beating up all the buildings and the Spitfires and Hurricanes parked out on its airfield. There was no let-up and at 15.34 Flt Lt Walter Dring led a force of eight Typhoons to ‘attack’ RAF Stoney Cross, 4 miles north-west of Lyndhurst in the New Forest. This frantic war-game programme continued for a few more days until the squadron was moved to RAF Colerne, near Bath, during March 1943.

Little operational flying was undertaken from Colerne and on 8 March it was all change again, now to RAF Gatwick where a unit known as No 123 Airfield was based and No 183 was to join that organisation. No 123 Airfield was the slightly strange collective name given to encompass the three squadrons now based on the airfield. Such units were highly mobile and would act like a completely mobile ‘airfield’, moving from place to place in convoy, taking with them literally every facility that several squadrons could normally expect to find on a permanent airfield. In the midst of all this to-ing and fro-ing, with the help of a borrowed Hurricane, Walter flew from Colerne to RAF Peterhead to spend a precious, all-too-short couple of days with the love of his life, Sheila, who had been posted to that far distant corner of the land.