The Wrong Grave (4 page)

She folded up the poetry, wedged it inside St. Francis, and fixed the Ganesh head back on. Maybe Miles would find it someday. She would have liked to see the look on his face.

We don't often get a chance to see our dead. Still less often do we know them when we see them. Mrs. Baldwin's eyes opened. She looked up and saw the dead girl and smiled. She said, “Bethany.”

Bethany sat down on her mother's bed. She took her mother's hand. If Mrs. Baldwin thought Bethany's hand was cold, she didn't say so. She held on tightly. “I was dreaming about you,” she told Bethany. “You were in an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical.”

“It was just a dream,” Bethany said.

Mrs. Baldwin reached up and touched a piece of Bethany's hair with her other hand. “You've changed your hair,” she said.

“I like it.”

They were both silent. Bethany's hair stayed very still. Perhaps it felt flattered.

“Thank you for coming back,” Mrs. Baldwin said at last.

“I can't stay,” Bethany said.

Mrs. Baldwin held her daughter's hand tighter. “I'll go with you. That's why you've come, isn't it? Because I'm dead too?”

Bethany shook her head. “No. Sorry. You're not dead. It's Miles's fault. He dug me up.”

“He did what?” Mrs. Baldwin said. She forgot the small, lowering unhappiness of discovering that she was not dead after all.

“He wanted his poetry back,” Bethany said. “The poems he gave me.”

“That idiot,” Mrs. Baldwin said. It was exactly the sort of thing she expected of Miles, but only with the advantage of hindsight, because how could you really expect such a thing. “What did you do to him?”

“I played a good joke on him,” Bethany said. She'd never really tried to explain her relationship with Miles to her mother. It seemed especially pointless now. She wriggled her fingers, and her mother instantly let go of Bethany's hand.

Being a former Buddhist, Mrs. Baldwin had always understood that when you hold onto your children too tightly, you end up pushing them away instead. Except that after Bethany had died, she wished she'd held on a little tighter. She drank up Bethany with her eyes. She noted the tattoo on Bethany's arm with both disapproval and delight. Disapproval, because one day Bethany might regret getting a tattoo of a cobra that wrapped all the way around her bicep. Delight, because something about the tattoo suggested Bethany was really here. That this wasn't just a dream. Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals were one thing. But she would never have dreamed that her daughter was alive again and tattooed and wearing long, writhing, midnight tails of hair.

“I have to go,” Bethany said. She had turned her head a little, towards the window, as if she were listening for something far away.

“Oh,” her mother said, trying to sound as if she didn't mind. She didn't want to ask: Will you come back? She was a lapsed Buddhist, but not so very lapsed, after all. She was still working to relinquish all desire, all hope, all self. When a person like Mrs. Baldwin suddenly finds that her life has been dismantled by a great catastrophe, she may then hold on to her belief as if to a life raft, even if the belief is this: that one should hold on to nothing. Mrs. Baldwin had taken her Buddhism very seriously, once, before substitute teaching had knocked it out of her.

Bethany stood up. “I'm sorry I wrecked the car,” she said, although this wasn't completely true. If she'd still been alive, she would have been sorry. But she was dead. She didn't know how to be sorry anymore. And the longer she stayed, the more likely it seemed that her hair would do something truly terrible. Her hair was not good Buddhist hair. It did not love the living world or the things in the living world, and it

did not love them

in an utterly unenlightened way. There was nothing of light or enlightenment about Bethany's hair. It knew nothing of hope, but it had desires and ambitions. It's best not to speak of those ambitions. As for the tattoo, it wanted to be left alone. And to be allowed to eat people, just every once in a while.

When Bethany stood up, Mrs. Baldwin said suddenly, “I've been thinking I might give up substitute teaching.”

Bethany waited.

“I might go to Japan to teach English,” Mrs. Baldwin said. “Sell the house, just pack up and go. Is that okay with you? Do you mind?”

Bethany didn't mind. She bent over and kissed her mother on her forehead. She left a smear of cherry ChapStick. When she had gone, Mrs. Baldwin got up and put on her bathrobe, the one with white cranes and frogs. She went downstairs and made coffee and sat at the kitchen table for a long time, staring at nothing. Her coffee got cold and she never even noticed.

The dead girl left town as the sun was coming up. I won't tell you where she went. Maybe she joined the circus and took part in daring trapeze acts that put her hair to good use, kept it from getting bored and plotting the destruction of all that is good and pure and lovely. Maybe she shaved her head and went on a pilgrimage to some remote lamasery and came back as a superhero with a dark past and some kick-ass martial-arts moves. Maybe she sent her mother postcards from time to time. Maybe she wrote them as part of her circus act, using the tips of her hair, dipping them into an inkwell. These postcards, not to mention her calligraphic scrolls, are highly sought after by collectors nowadays. I have two.

Miles stopped writing poetry for several years. He never went back to get his bike. He stayed away from graveyards and also from girls with long hair. The last I heard, he had a job writing topical haikus for the Weather Channel. One of his best-known haikus is the one about tropical storm Suzy. It goes something like this:

A young girl passes

in a hurry. Hair uncombed.

Full of black devils.

Wizards are always hungry.

THE WOMAN WHO

sold leech grass baskets and pickled beets in the Perfil market took pity on Onion's aunt. “On your own, my love?”

Onion's aunt nodded. She was still holding out the earrings which she'd hoped someone would buy. There was a train leaving in the morning for Qual, but the tickets were dear. Her daughter Halsa, Onion's cousin, was sulking. She'd wanted the earrings for herself. The twins held hands and stared about the market.

Onion thought the beets were more beautiful than the earrings, which had belonged to his mother. The beets were rich and velvety and mysterious as pickled stars in shining jars. Onion had had nothing to eat all day. His stomach was empty, and his head was full of the thoughts of the people in the market: Halsa thinking of the earrings, the market woman's disinterested kindness, his aunt's dull worry. There was a man at another stall whose wife was sick. She was coughing up blood. A girl went by. She was thinking about a man who had gone to the war. The man wouldn't come back. Onion went back to thinking about the beets.

“Just you to look after all these children,” the market woman said. “These are bad times. Where's your lot from?”

“Come from Labbit, and Larch before that,” Onion's aunt said. “We're trying to get to Qual. My husband had family there. I have these earrings and these candlesticks.”

The woman shook her head. “No one will buy these,” she said. “Not for any good price. The market is full of refugees selling off their bits and pieces.”

Onion's aunt said, “Then what should I do?” She didn't seem to expect an answer, but the woman said, “There's a man who comes to the market today, who buys children for the wizards of Perfil. He pays good money and they say that the children are treated well.”

All wizards are strange, but the wizards of Perfil are strangest of all. They build tall towers in the marshes of Perfil, and there they live like anchorites in lonely little rooms at the top of their towers. They rarely come down at all, and no one is sure what their magic is good for. There are balls of sickly green fire that dash around the marshes at night, hunting for who knows what, and sometimes a tower tumbles down and then the prickly reeds and marsh lilies that look like ghostly white hands grow up over the tumbled stones and the marsh mud sucks the rubble down.

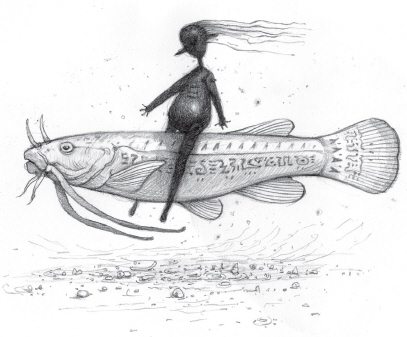

Everyone knows that there are wizard bones under the marsh mud and that the fish and the birds that live in the marsh are strange creatures. They have got magic in them. Children dare each other to go into the marsh and catch fish. Sometimes when a brave child catches a fish in the murky, muddy marsh pools, the fish will call the child by name and beg to be released. And if you don't let that fish go, it will tell you, gasping for air, when and how you will die. And if you cook the fish and eat it, you will dream wizard dreams. But if you let your fish go, it will tell you a secret.

This is what the people of Perfil say about the wizards of Perfil.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil talk to demons and hate sunlight and have long twitching noses like rats. They never bathe.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil are hundreds and hundreds of years old. They sit and dangle their fishing lines out of the windows of their towers and they use magic to bait their hooks. They eat their fish raw and they throw the fish bones out of the window the same way that they empty their chamber pots. The wizards of Perfil have filthy habits and no manners at all.

Everyone knows that the wizards of Perfil eat children when they grow tired of fish.

This is what Halsa told her brothers and Onion while Onion's aunt bargained in the Perfil markets with the wizard's secretary.

The wizard's secretary was a man named Tolcet and he wore a sword in his belt. He was a black man with white-pink spatters on his face and across the backs of his hands. Onion had never seen a man who was two colors.

Tolcet gave Onion and his cousins pieces of candy. He said to Onion's aunt, “Can any of them sing?”

Onion's aunt indicated that the children should sing. The twins, Mik and Bonti, had strong, clear soprano voices, and when Halsa sang, everyone in the market fell silent and listened. Halsa's voice was like honey and sunlight and sweet water.

Onion loved to sing, but no one loved to hear it. When it was his turn and he opened his mouth to sing, he thought of his mother and tears came to his eyes. The song that came out of his mouth wasn't one he knew. It wasn't even in a proper language and Halsa crossed her eyes and stuck out her tongue. Onion went on singing.

“Enough,” Tolcet said. He pointed at Onion. “You sing like a toad, boy. Do you know when to be quiet?”

“He's quiet,” Onion's aunt said. “His parents are dead. He doesn't eat much, and he's strong enough. We walked here from Larch. And he's not afraid of witchy folk, begging your pardon. There were no wizards in Larch, but his mother could find things when you lost them. She could charm your cows so that they always came home.”

“How old is he?” Tolcet said.

“Eleven,” Onion's aunt said, and Tolcet grunted.

“Small for his age.” Tolcet looked at Onion. He looked at Halsa, who crossed her arms and scowled hard. “Will you come with me, boy?”

Onion's aunt nudged him. He nodded.

“I'm sorry for it,” his aunt said to Onion, “but it can't be helped. I promised your mother I'd see you were taken care of. This is the best I can do.”

Onion said nothing. He knew his aunt would have sold Halsa to the wizard's secretary and hoped it was a piece of luck for her daughter. But there was also a part of his aunt that was glad that Tolcet wanted Onion instead. Onion could see it in her mind.

Tolcet paid Onion's aunt twenty-four brass fish, which was slightly more than it had cost to bury Onion's parents, but slightly less than Onion's father had paid for their best milk cow, two years before. It was important to know how much things were worth. The cow was dead and so was Onion's father.

“Be

good,”

Onion's aunt said. “Here. Take this.” She gave Onion one of the earrings that had belonged to his mother. It was shaped like a snake. Its writhing tail hooked into its narrow mouth, and Onion had always wondered if the snake was surprised about that, to end up with a mouthful of itself like that, for all eternity. Or maybe it was eternally furious, like Halsa.

Halsa's mouth was screwed up like a button. When she hugged Onion good-bye, she said, “Brat. Give it to me.” Halsa had already taken the wooden horse that Onion's father had carved, and Onion's knife, the one with the bone handle.

Onion tried to pull away, but she held him tightly, as if she couldn't bear to let him go. “He wants to eat you,” she said. “The wizard will put you in an oven and roast you like a suckling pig. So give me the earring. Suckling pigs don't need earrings.”

Onion wriggled away. The wizard's secretary was watching, and Onion wondered if he'd heard Halsa. Of course, anyone who wanted a child to eat would have taken Halsa, not Onion. Halsa was older and bigger and plumper. Then again, anyone who looked hard at Halsa would suspect she would taste sour and unpleasant. The only sweetness in Halsa was in her singing. Even Onion loved to listen to Halsa when she sang.