The Worst Hard Time (6 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Five flags had flown over No Man's Land. Spain was the first to claim it, but two expeditions and reports from traders reinforced the view that the land was best left to the "humped-back cows" and their pursuers, the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache. Spain gave the territory to Napoleon. The French flag flew for all of twenty days, until the emperor turned around and sold it to the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase. A subsequent survey put the land in Mexico's hands, an extension of their rule over Texas in 1819. Seventeen years later, the newly independent Republic of Texas claimed all territory north to Colorado. But when Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845, it was on the condition that no new slave territory would rise above 36.5 degrees in latitude, the old Missouri Compromise line. That left an orphaned rectangle, 35 miles wide and 210 miles long, that was not attached to any territory or state in the West, and it got its name, No Man's Land. The eastern boundary, at the one hundredth meridian, was where the plains turned unlivably arid, unfit for Jefferson's farmer-townbuilders.

In the late nineteenth century, one corner of the Panhandle served as a roost for outlaws, thieves, and killers. The Coe Gang was known for dressing like Indians while attacking wagon trains on the Cimarron Cutoff. The Santa Fe Railroad pushed a line as far as Liberal, Kansas, on the Panhandle border, in 1888. Kansas was dry. And so a place called Beer City sprang up just across the state line: a hive of bars, brothels, gambling houses, smuggling dens, and town developers on the run. The first settlement in No Man's Land, Beer City lasted barely two years before it was carted away in pieces. Law, taxes, and land title companies finally came to the Panhandle in 1890, when the long, undesired stretch was stitched to Oklahoma Territory.

The name

Oklahoma

is a combination of two Choctaw wordsâ

okla,

which means "people," and

humma,

the word for "red." The red people lost the land in real estate stampedes that produced instant townsâOklahoma City, Norman, and Guthrie among them. But the great land rushes never made it out to the Panhandle. No Man's Land was settled, finally, when there was no other land left to take.

It was a hard place to love; a tableau for mischief and sudden death from the sky or up from the ground. Hazel Lucas, a daring little girl with straw-colored hair, first saw the grasslands near the end of a family journey to claim a homestead. Hazel got up on the tips of her toes in the horse-drawn wagon to stare into an abyss of beige. It was as empty as the back end of a day, a wilderness of flat. The family clawed a hole in the side of the prairie just south of Boise City. It was not the promised land Hazel had imagined, but it had ... possibility. She was thrilled to be at the beginning of a grand adventure, the first wave of humans to try to mate with this land. She also felt scared, because it was so foreign. The lure was price, her daddy said. This land was the only bargain left in America. The XIT property, just thirty miles to the south, could cost a family nearly $10,000 for a half-section. Here it was free, though there was not much left to claim. By 1910, almost two hundred million acres nationwide had been patented by homesteaders, more than half of it in the Great Plains. Hazel missed trees. She wanted just one sturdy elm with a branch strong enough to hold a swing. And she didn't want to live in a hole in the ground, with the snakes and tarantulas, and sleeping so near to the stink of burning

cow manure. Nor did she want to live in a sod house, the prairie grass stacked like ice blocks of an igloo. Soddies leaked. Friends who had been in the Panhandle long enough to make their peace with it told the Lucas folks that if a person wore out two pair of shoes in this country, they would never leave. You just had to give this land some time to make it work.

Hazel's family arrived in No Man's Land in 1914, the peak year for homesteads in the twentieth centuryâ53,000 claims made throughout the Great Plains. Every man a landlord! But people were already fleeing the northern plains, barely five years after passage of the Enlarged Homestead Act. The northern exodus should have been a warning that the attempt to cover the prairie with "speckled cattle and festive cowboys," as General Sheridan had said, was a mistake. Places like Choteau County, Montana, lost half their population between 1910 and 1930, while Cimarron County, Oklahoma, grew by 70 percent and Dallam County, Texas (home of Dalhart), doubled its population during the same time. The killer wintersâtemperatures of minus forty in Montana froze farm animals in placeâwere not a

problem in the southern plains, people told themselves. Just get your piece of the grassland and go to it.

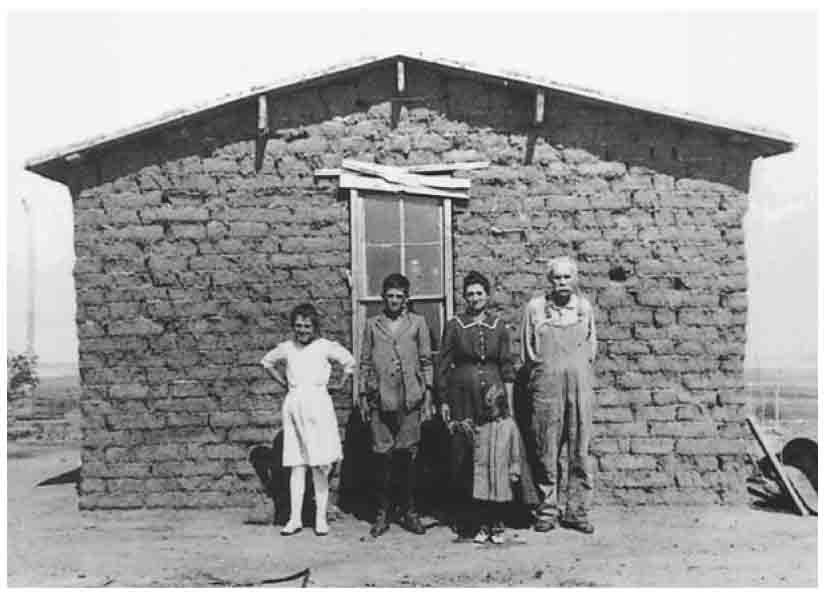

Family and their sod house, No Man's Land, date unknown

The federal government was so anxious to settle No Man's Land that they offered free train rides to pilgrims looking to prove up a piece of dry land, just as XIT realtors had done. The slogan was "Health, Wealth, and Opportunity." Hazel's father, William Carlyle, known as Carlie, built a dugout in 1915 for his family and started plowing the grass on his half-section, a patch of sandy loam. The home was twenty-two feet long by fourteen feet wideâ308 square feet for a family of seven.

Without a windmill, the Lucas family would not have lasted a day, nor would much of the High Plains been settled. Windmills came west with the railroads, which needed large amounts of water to cool the engines and generate steam. It was a Yankee mechanic, Daniel Halladay, who fashioned a smaller version of bigger Dutch windmills. The Union Pacific Railroad was his first big customer. Eventually, a nester could buy a windmill kit for about seventy-five dollars. Some people hit water at thirty feet, others had to go three times as deep. Some dug the hole by hand, a grueling task, prone to cave-ins; others used steam or horse-powered drills. Once the aquifer was breached, a single wooden-towered windmill could furnish enough water for most farming needs on a full section of land. The pumps broke down often, and parts were hard to come by. But nesters were convinced they had tapped into a vein of life-giving fluid that would never give out. Don't just look at the grass and sky, they were advised; imagine a vast lake just below the surface.

"No purer water ever came out of the ground," a real estate brochure circulating through the Panhandle in 1908 claimed. "The supply is inexhaustible."

In trying to come to terms with a strange land, perhaps the biggest fear was fire. The combination of wind, heat, lightning, and combustible grass was nature's perfect recipe for fire. One day the grass could look sweet and green, spread across the face of No Man's Land. Another day it would be a roaring flank of smoke and flame, marching toward the dugout. Hazel Lucas was petrified of prairie fires, and for good reason. A few years before the family arrived, a lightning bolt lit

up a field in New Mexico, igniting a fire that swept across the High Plains of Texas and Oklahoma. It burned everything in its wake for two hundred miles. Fire was part of the prairie ecosystem, a way for the land to regenerate itself, clean out excess insect populations, and allow the grass to be renewed. The year after a fire, the grass never looked healthier. Cattle, planted on the land for only a few years, tried fleeing the big fires, but they were often burned or trampled to death. Nesters frantically dug trenches or berms around their homes, hoping to create buffer lines. Sometimes a rolling blaze skipped over a dugout; other times it snuffed the roof and smoked out everything else. Pushed by the winds, a prairie fire moved so quickly it was difficult for a person on horseback to outrun it.

But some people felt immune. Once, a preacher joined a postal carrier making his rounds in No Man's Land. The sky turned black and lightning flashed. Bolts struck the ground and electrified barbed-wire fences. The preacher cowered for cover. The carrier told him to relax. "God isn't that awful," he said. "Lightning will never strike a mailman or a preacher." Within ten years, God would change moods.

When it wasn't fire, it was another element on the run in No Man's Land. The year the Lucas family arrived in the Panhandle, the worst flood in young Cimarron County's history terrorized a string of ranches and homesteads. Most of the year, the Cimarron River skulks meekly away to the east, a barely discernible trickle in midsummer. But in the spring of 1914, after a week of steady rains, the Cimarron jumped its banks and went on a rampage. The flood knocked out a dam that had just been completed, carried a thirteen-room ranch house into the river, and washed away numerous homes. Two children drowned.

Even the entertainment could be traumatic. People would gather at makeshift rodeo stands near Boise City on Saturday afternoons to watch the cow dip. Cattle were herded into a chute and down into a vat of water. Once they hit the water, they were drowned by two cowboys, on either side of the vat, who held their heads down while the beeves bucked. Some of the children didn't like itâan amusement ride with sudden death at the end.

The Lucas family stayed through the fires, the floods, and the peculiar social life because the land was starting to pay. Not as grassland for cattle, but as crop-producing dirt. Carlie dug up part of his half-section using a horse-drawn walking plow and planted it in wheat and corn. The Great War, starting in 1914, meant a fortune was about to be made in the most denigrated part of America, all of the dryland wheat belt. Turn the ground, Lucas was advised, as fast as you can.

Within a few years, the family built a home above ground, rising from their dugout in line with thousands of other prospectors of wheat. They bought lumber, nails, siding, and roofing material from the rail town of Texhoma, forty miles southeast, and went about building a frame house, with living room, kitchen, bedrooms, fruit cellar, trim, shingles, and large windows. The door faced south, a necessity in No Man's Land to keep the northers from blowing cold into the new abode. Framing timber around the bright Oklahoma sky, the Lucas family dreamed of space enough to play music and cook without bumping into each other, or falling to sleep at night without having to scan the floor for snakes. But just as the new house was starting to take shape, a musclebound blow arrived one spring afternoon, strong enough to knock a person down. They fled into the old dugout next door. The wind screeched, tugging at the new house. It was a steady roar, not a gale. On the morning of the second day, they heard

the awful clank of crumbling timbers. Hazel Lucas poked her head above the dugout and saw in a swirl of dust and wood chips that their new home was being carried upward and away with the wind. The storm took the entire house. After four days, the family went searching the prairie, looking for pieces of their home.

Dugout homestead, Blaine County, Oklahoma Territory, 1894

For all the horror, the land was not without its magic. The first Anglos in the Panhandle used to recite a little ditty:

I like this country fine

I think it's awfully good.

For the wind pumps all the water

And the cow chops all the wood.

After a rain- or hailstorm had rumbled through, the sky was open and embracing, the breeze only a soft whisper against the songs of meadowlarks and cooing of doves. A prairie chicken doing its mating dance, its full-breasted plumage in a heave of sexual pride, was a thing to see. So was a pronghorn antelope coming through the grass, bouncing out of a wallow. Robin's egg blue was the color of mornings without fear. At night, you could see the stars behind the stars. Infinity was never an abstraction on the High Plains.

Hazel Lucas would ride her horse Pecos over the prairie to visit with the James boys, one of the last big ranching families, whose spread touched parts of Texas and Oklahoma. There was Walter and Mettie and their kids Andy, Jesse, Peachey, Joe Bob, Newt, and Fannie Sue. The boys could ride, rope, and cuss better than anyone in Boise City, and the stories they told made a girl feel she was being allowed into a secretâand vanishingâworld. Andy was a bit of a mysterious presence and had a swagger that drew people to him. He would disappear for five days at a time, then show up suddenly in Boise City.