The Worst Hard Time (28 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

"It is hard to be old and not have anything," a widowed North Dakota farmer's wife wrote the president in 1934, in a letter that was typical in its pleading tone. "I have always been poor and have always worked hard, so now I am not able to do any more. I am all worn out but am able to be around and I thank God that I have no pains."

Loumiza was in pain. The dust filtered into her home like a toxic vapor. She stopped eating. She grew weaker. Every time she brought

her teeth together she tasted grit. Her bedroom was a refuge but not a pleasant one. It was a dusty hole in a homestead. She could not be moved because the risk of travel exposed her to the wind-borne sand. Her family begged her to eat. She withdrew deeper under the pile of quilts. The windows were sealed so tightly that light from her beloved land was completely blocked. It did not matter: she hated what No Man's Land had become. It was better to remember it as it was when she came into this country, arriving by covered wagon to Texhoma, and north to a half-section of their own, her and Jimmy, in the free kingdom of No Man's Land. That high bluestem in the corner of the county, tall as the reach of a scarecrow, that carpet of buffalo grass, and Lord what the rains could do in a good yearâit was what the land was supposed to look like.

Grandma Lou seemed more worried about her youngest great-granddaughter, the baby Ruth Nell, than her own health. She waved off the questions about her diminishing spirit and asked about Ruth Nell, and she prayed. She clutched the one Bible she had carried throughout her life, a tattered thing that had traveled across time and terrain. As the dusters picked up, some of Lou's friends and even some of her own family believed the terrible storms were a fulfillment of Biblical prophecyâa sign of the final days. But Lou knew better. There was nothing in her Bible that said the world would end in darkness and dust.

Two days before Ruth Nell's first birthday, Hazel and her husband decided to flee, breaking the family apart for the health of the baby, as the doctor had recommended. They had to get out now or risk the baby's life. This year, 1935, had been one duster after the other and April showed no sign of letup, no rain in the forecast, four years into the drought. At the end of March, black blizzards had fallen for twelve straight days. During one of those storms, the wind was clocked at forty miles an hour or betterâfor a hundred hours. The

Boise City News

said it was the worst storm in the history of the county. Schools closed, again. An emergency call went out: come get the children and take them home. The schools would reopen when it was safe. Boise City looked ghostly, shuttered from the storms, hunkered down like an abandoned outpost in the Sahara. All the windows were cloaked in

brown. Cars that had shorted out on the static were left in roads or ditches, and they soon were covered and became lumps in the sand.

Hazel hurried along her plan to get Ruth Nell out of Boise City. She arranged to stay with her in-laws in Enid, Oklahoma, well to the east. But just as they were ready to depart, a tornado touched down not far from Enid, the black funnel dancing around the edges of the very place where Ruth Nell was to find her refuge. It was a gruesome thing, ripping through homes, throwing roofs to the sky. Now whatâstay or go? Hazel and Charles felt they had no choice but to go. It was more dangerous living in Boise City, and if they waited much longer, they might not get out of town. The coffee-box baby haunted Hazel, the little blue-faced infant left in the cold who had died of dust pneumonia.

Sheriff Barrick said the roads out of town were blocked by huge drifts. The CCC crews would no sooner dig out one drift than another would appear, covering a quarter-mile section of road. A caravan of Boise City residents who had tried to leave earlier in the week with all their belongings loaded into their jalopies was pinned down at the edge of town, and they were forced to return. The volume of dirt that had been thrown to the skies was extraordinary. A professor

at Kansas State College estimated that if a line of trucks ninety-six miles long hauled ten full loads a day, it would take a year to transport the dirt that had blown from one side of Kansas to the otherâa total of forty-six million truckloads. Better days were not in the forecast.

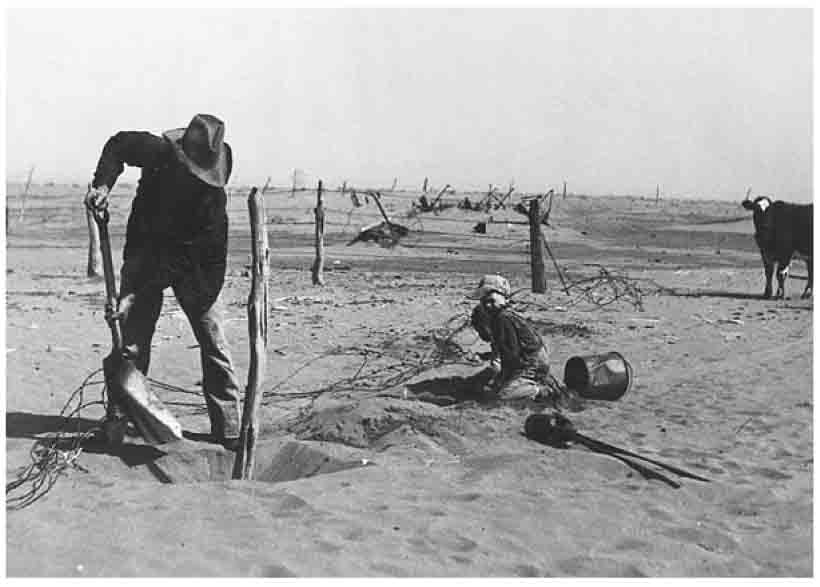

Digging out fence posts, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, 1936

Hazel made it south to Texhoma, where she and Ruth Nell could ride the train to the eastern part of the state. If the baby could take in some clean air for a few weeks, living with her grandparents, she might shake this horrid cough. The journey to Enid was not easy. A few weeks earlier, a train full of CCC workers slid off the dust-covered tracks and rolled, killing several young men. Hazel's train sputtered its way east, stopping frequently so the crews could shovel sand from the tracks. Hazel tried to stay positive, but it looked awful outside: all of the Oklahoma Panhandle blowing and dead, no life of any form in the fields, no spring planting, no farmers on the roads. By the time mother and daughter made it to Enid, the baby's cough was no better. Her little stomach must have been in acute pain from the hacking, and she might have fractured a rib from coughing, for the baby cried constantly. At times, Hazel cried along with her and prayed intensely, hoping for relief. Arriving in Enid, Hazel rushed Ruth Nell to St. Mary's Hospital. The doctors tried to clean out her lungs by suctioning some of the gunk, but the baby would not settle. She coughed and cried, coughed and cried. The doctors confirmed Hazel's fearsâRuth Nell had dust pneumonia. She was moved into a section of the hospital in Enid that nurses called the "dust ward." The baby's temperature held above 103. She could not hold down milk from a bottle; it came back up as spit and grime. The doctors wrapped the baby's midsection in gauze and loose-fitting tape, as a way to hold in place the fractured ribs and diminish the pain in the stomach muscle. Still, Ruth Nell coughed and cried, coughed and cried.

"You must come," Hazel phoned her husband from the hospital in Enid. "Come now. Ruth Nell looks terrible. I'm so afraid."

Charles got in his car and plowed through the dust, trying to make his way east. Just getting to Guymon, one county over, proved hazardous. He had his head out the window the whole way, as he had done a year earlier during Ruth's birth, but this time the sand blinded him. He wore goggles and a respiratory mask but they clogged quickly and

he was forced to remove them both. Once the car veered off the road and tipped, and it seemed like he was going to crash it again. He decided to drive along the ditch, with two wheels below grade and the other two wheels on the road. It was the only way to move forward through the haze and be sure of his direction. It was nearly three hundred miles to Enid, a drive of two days, moving slowly along the ditch. He kept going at night, with the headlights on. In order to drive halfway in the ditch, Charles had to bring up the chain that usually dragged below the car because it picked up too much debrisâmostly dust-encrusted tumbleweeds. Without the chain, though, his car had no way to ground the static. What he needed was a lull between dusters. He got his wish during the first hundred miles. But midway into his journey, he drove into a duster and the static shorted his car. He was stranded.

He kicked the vehicle, coughed up a fistful of gunk, and shook the sand from his hair. He lubricated his nose with Vaseline and waited for the duster to pass, imagining his baby girl gasping in the hospital. After nearly an hour, the black blizzard dissipated, and Charles was able to restart the car.

By the time Charles made it to St. Mary's Hospital, he was covered in dirt, his face black. He went to the dust ward. Hazel was crying. Ruth Nell had died an hour earlier. She knew by the look on the doctor's face when he came to her with his hands up.

"I'm sorryâyour baby is dead."

Back in No Man's Land, Hazel's Grandma Lou stopped coughing. She had been running a fever for several days and could not hold down food.

"How's the baby?" she asked. "How is Ruth Nell? Any word?"

Her son had not heard. Loumiza turned away and closed her eyes. She would not see the homestead green again, would not see any more of the starving land. She slipped under layers of quilt and took her last breath, dying within hours after her youngest great-grandchild fell. The family decided to stage a double funeral for baby Ruth Nell and the Lucas family matriarch. They would hold a ceremony at the church in Boise City, then proceed out of town to a family plot for burial on Sunday, April 14, 1935.

T

HE DAY BEGAN

as smooth and light as the inside of an alabaster bowl. After a siege of black and white, after a monotonous jumble of grit-filled clouds had menaced people on the High Plains for seasons on end, the second Sunday in April was an answered prayer. Sunrise was pink with streaks of turquoise, a theatrical start. The air was clear. The horizon stretched to infinity once again, the sky scrubbed. There was no wind. The sun infused every gray corner with a spring glow. Nesters crawled out of their dugouts and shanties, their two-room frame houses and mud-packed brick abodes, like soldiers after a long battle. For once, they did not have to put on goggles or attach the sponge masks or lubricate their nostrils before going outside. They stretched their legs and breathed deep, blinking at the purity of a prairie morning, the smell of tomorrow again in the air. The land around them was tossed about and dusted over, as lifeless as the pockmarked fields of France after years of trench warfare. Trees were skeletal. Gardens were burned and limp, electrocuted by static from the spate of recent dusters. Still, the day had enough promise to remind people why they had dug homes into the skin of the southern plains, and some dared to entertain a thought on this morning: perhaps the worst was over.

Where to start? Windows were unsealed and opened wide, the heavy, dirt-laden sheets removed. Some windows had been sealed so tightly with wind-hardened dust that they would not budge. It was spirit-lifting to actually let clean air and sunshine inside. Going room

to room with a scoop shovel, it was easy to fill a large garbage can with dirt. Roofs had to be shoveled, ceilings as well. Some ceilings had collapsed. Many were sagging. People cut holes overhead, crawled up, and pushed dust through the opening. Bed sheets, towels, clothes could be washed and allowed to dry in this sun, and they would smell of the plains on its best day. Outside, the cows would get a good scrubbing and drink from holding tanks without taking in grit. The cows looked so worn down, having lost patches of hair to the dust, their skin raw and chapped, their teeth chipped by chewing sandpaper with every meal, their gums inflamed. Chickens were due a run of the yard, fluffing sand out of their feathers. A horse might get its nostrils cleaned and find a stretch where it could gallop without sinking up to its knees in drifting sand.

A "grand and glorious" rabbit drive, as the

Boise City News

called it, was back on after a month-long delay because of dusters. A preacher had warned people they should not club rabbits on the Sabbath, that they would rouse the Lord to anger. But today the weather was flawless, a chance to kill maybe fifty thousand rabbits. And it seemed to some nesters like the perfect way to vent their frustration over a collision of bad daysâforty-nine dusters in the last three months, according to the weather bureau.

Roy Butterbaugh, a musician by tradeâsax and clarinetâwho had bought the

Boise City News

on a lark a few years earlier, thought it was time to leave behind the bonds of this broken earth. He wanted to fly. The dusters had made him claustrophobic. Oh, to stretch out, to get above the dead ground and float in the blue and the sunshine. A friend had a little single-engine airplane at the edge of the town, next to the dirt strip that served as a runway. It did not take much to talk Butterbaugh into going for a spin in the clean air.

Church sounded right. This was Palm Sundayâa week before Easter, the start of the holiest time on the Christian calendar. God had to be in a forgiving mood or else why would the day be so wondrous? With weather like this, No Man's Land needed only a couple of good rainstorms and fields would once again be fertile, said a minister in his Sunday sermon in Boise City. But they had to pray in order for this to happen. Some who wanted to go to church were too embarrassed by

how they looked. Little Jeanne Clark, who had just left the hospital in Lamar after a long bout of dust pneumonia, only had dresses made of sackcloth, with the onion brand names printed on the side. She could not go to church in such a thing; the other children would laugh at her.

In Baca County, Ike Osteen did extra chores around the dugout. After being cooped up so long in the pocket of home, Ike had a burst of energy. The dusters had been so thick through February and March that the half-section looked unfamiliar. He was seventeen now, a young man with an itch to get on with life. He wandered about the 320 acres of Osteen family ground, trying to find a familiar landmark. The orchard was dead and covered. A dune, perhaps six feet high at the top, had formed along the length of the tree line. It looked like a wave frozen in place. He saw prints in the sand from jackrabbits and heard a sound that had just arrived for the first time this withered springâbirdsong. Where would they nest? Maybe find a corner of the barn that had not been dusted. The garden space, where the Osteens had grown lettuce, tomatoes, carrots, sweet potatoes, and corn for popping, was under a drift grave. Implements and machines were buried. Ike found the tops of cultivator wheels and a horse-drawn buggy used by his late daddy. But only the tops. He thought of digging them out, but he would need more help than he could get from his two sisters and brother in the dugout. And where had all the topsoil gone? What state now held the Osteen farm? In places where dunes had not piled up, Ike found a couple of arrowheads. As he picked at the hardened dirt, he thought it might be an Indian burial ground, laid bare by the winds. He could see the outline of graves, and they made him wonder what the Comanche would do if they rose from the dead and found the buffalo grass gone and the land destroyed.