The Witling (17 page)

“As I was saying,” Bre’en resumed, “these devices only increased our respect for you. We lost two good men learning that this”—he pointed at one of the machine pistols—“rengs metal pebbles as fast-moving as anything our soldiers can reng. With this weapon, an untraveled recruit can be as deadly as a trooper who has spent years on pilgrimage.”

Ah, the armies you could raise, eh, Bre’en?

thought Leg-Wot.

The Snowman reached across the table to touch the maser. “And this device proved almost as deadly. One of our men looked down the glassy end, while turning these knobs. He died in seconds, almost as though he had been kenged—yet the fellow was alert and fully Talented.”

Bjault’s voice was hesitant. “What exactly do you want from us?”

“The secret of your magic. Failing that, we want you to build us more of these things. We’d like to catch some of those sky monsters, too. In return you will have our assistance in your efforts to travel across the sea. Or, if you decide to remain in our kingdom permanently, we will offer you an honored place in our peerage.”

Ajão nodded, and Leg-Wot wondered angrily if the old man really bought such promises. “May I talk with Yoninne?” he asked.

Pelio growled a curse under his breath.

“Certainly,” said Bre’en, but the Snowman made no move to give them privacy.

Leg-Wot looked across the piled furs. “Well?” she said in Homespeech.

“Well,” said Ajão in the same language, his voice as tremulous as before, “we’re going to have to make this quick. Pelio’s right; they murdered the crew. You just don’t suffocate people with CO

2

and then leave them ‘asleep’ until you need them. You either revive them immediately or else they die.”

Samadhom, poor Samadhom.

It wasn’t right, but somehow the tubby watchbear’s death hurt the most.

“These are clever people, Yoninne. I think they revived Pelio just so they could make the points they did. Tru‘ud’s court has the taint of a ‘modern’ dictatorship—like we had at the end of the Interregnum. Those servants—no, don’t turn to look; Bre’en and the others don’t understand our language but they might be able to read your face—those servants are alike enough to be brothers. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Snowking breeds witlings like cattle.

“I suspect Tru’ud will eliminate us the moment he thinks we’ve given him a decisive advantage over his enemies—though we’ll die of metallic poisoning long before that happens.”

Perhaps Bjault wasn’t quite the ivory-tower man he seemed. “Well then, damn it, what are we going to do?” Out of the corner of her eye she saw that the Snowmen were becoming restless.

“I … I don’t know, Yoninne,” he said and Leg-Wot knew that here, at least, the indecision in his voice was real. “It looks as though we’ll have to play along—for the moment.”

“Hmf.” Yoninne turned back to the Snowking and his ministers. “We will cooperate, but Prince Pelio must not be harmed,” she said in Azhiri.

Bre’en nodded, and Pelio’s expression froze in an implacable glare.

I’m sorry, Pelio

, the thought came unexpectedly into her mind. She was still selling him out, even though she had secured him—temporary—safety.

Bre‘en was all smiles now, and even Tru’ud’s grim face seemed to hold a bit of triumph. “What you ask is only what we intended,” said the Snowman diplomat. “Your quarters have already been prepared and heated to the temperature Summerfolk find comfortable.”

Yoninne felt unwilling gratitude at this. Her body ached from the constant cold, and her sweat-soaked parka was like a clammy hand on her skin. A room temperature around freezing might be pleasant indoor warmth for Bre’en, but it was hideously uncomfortable for the likes of Pelio and Yoninne Leg-Wot-and it was probably hell for Bjault.

The three witlings stood, painfully aware of the cramps in their muscles. As they walked slowly down over the piled furs, Snowman troopers closed in around Ajão and Yoninne. Behind them, Pelio followed without so much as a single guard.

It’s Ajão and me they fear

, thought Leg-Wot. The two Novamerikans were wizards who must be carefully watched, especially when they came near their magical gadgets. Pelio, on the other hand, was less than no threat to the Snowmen.

Tru‘ud grunted something at Bre’en in the glottalized Snowman language; the diplomat walked around the table to the ablation skiff. “His Majesty is curious about this object. Since it’s off your yacht, we haven’t had a chance to examine it. It’s certainly the largest thing of yours we’ve seen; is it some kind of vehicle? A self-renging boat perhaps?” The Snowman pulled at the skiff’s circular hatch, which already stood ajar. The black ceramic port slid easily back and—

—Samadhom poked his furry muzzle over the lip of the entrance.

Meep?

he inquired curiously of the dumfounded Snowman. So that was where the animal had been holed up! Pelio had put him into what was probably the bestinsulated volume on the whole road boat—their own ablation skiff!

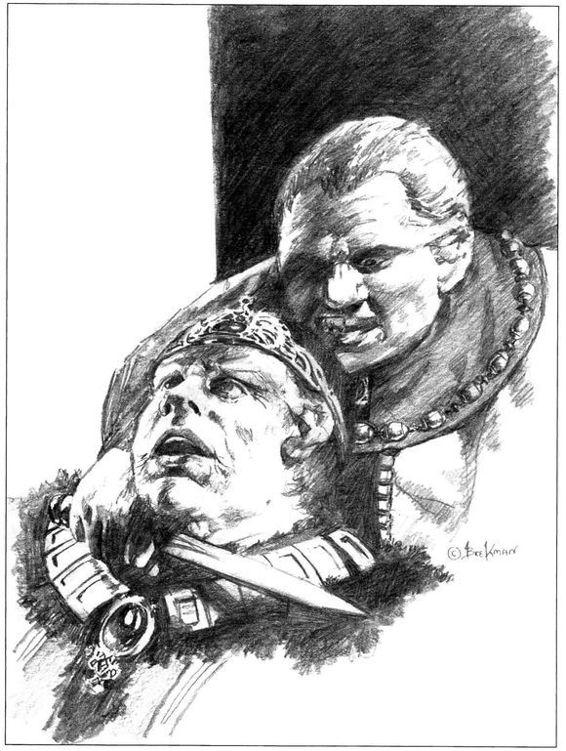

For just an instant, everyone stood frozen. Pelio was the first to recover, and what he did was as much a surprise as Samadhom’s sudden appearance. In a single motion he vaulted across the table, snatching up the short machete the Snowmen had stolen from the Novamerikans’ survival kit. Pelio twisted around as he landed, pulled Tru’ud off his seat, and slid the razor-sharp blade against the Snowman’s throat.

“Stand back—back!” Tru‘ud pitched against him and a thin line of red appeared across the king’s throat. For a moment Tru’ud’s men glared silently at the prince. Pelio’s face turned pale and Yoninne realized that the Snowmen had tried to scramble his insides. But Samadhom was protecting him—just as Yoninne had been protected when King Shozheru had attacked her.

She stepped quickly to the table, and swept up the maser. The needle on its power supply rested dead on zero. No matter. She turned and leveled the stubby tube at her erstwhile guards. “You heard Prince Pelio. Move.” The men slowly obeyed. Leg-Wot glanced at Tru’ud’s advisers by the far end of the table. “And you people. Stay away from those.” She waved the maser at the machine pistols.

As Bjault retrieved the weapons, Pelio relaxed his hold on Tru’ud a fraction and gave Yoninne a triumphant, mocking smile. “I guessed you two would fly whichever way the wind was blowing,” he said.

What could she say to that?

Ajão peered into the magazines of the two pistols. “One’s empty and the other is hopelessly jammed,” he said in Homespeech.

“The maser’s dead, too,” Yoninne replied in the same language. “But they don’t know that.”

“Well?” Pelio broke in angrily. “Do we return to our original plan? There’s no other choice now, you know.”

Yoninne nodded. Death might be seconds away, but somehow she was happier now than before—when life had depended on sucking up to the Snowmen; now it depended on fighting them. “But how?”

Pelio looked over his shoulder at a craft in the transit pool. “We’ll take that speedboat,” he said abruptly, carelessly. Tru‘ud twisted in his grip and Pelio bore down slightly with the machete. “We’ll go all the way to County Tsarang—with Tru’ud as our hostage!”

It was an insane plan, thought Leg-Wot. They were thousands of kilometers inside Snowman territory; any road they followed could be blocked by whole armies. Then she looked around the vast hall. Everyone—the servants, the troops, the advisers—stared in horror at the knife held on Tru’ud’s throat. Perhaps this dictatorship was not quite as modern as Bjault thought. She guessed the Snowmen would do anything in exchange for their king’s safety. Besides—as her father had often said—it’s far better to act on a bad plan than to wait for a good one to come along.

She turned to Bre’en. “All right, Snowman. We want passage north. Put that”—she waved at the skiff—“aboard the boat there, and give us a pilot who can navigate to County Tsarang.”

Bre’en spread his hands. Of all those present, he seemed the only one who had recovered his composure. “Such men are rare. Besides myself, I know of no one in the palace who could take you as far as the county’s border. You could, of course, change pilots along the way … Or you could reconsider. We still bear

you

no ill feeling.”

Leg-Wot smelled a rat. Changing pilots en route would be an invitation to disaster. And the alternative—taking Bre’en along with them—was almost as bad. The man was slippery.

“Why would you, of all people, know the way?” she asked.

The Snowman seemed almost relaxed now. He ignored the supposedly deadly maser pointed at his thick waist. “As a young man, I served in His Majesty’s army. I worked with Desertfolk between here and County Tsarang. I learned every road I could, so I wouldn’t have to depend on always having the right pilot available. Of course, most officers wouldn’t take the trouble, but I—”

“Be quiet, both of you,” said Pelio. “You’ll pilot us to County Tsarang, Bre‘en. But if you’re lying about your skill—” He pulled back hard on Tru’ud, half choking the man.

Ajão seemed on the point of raising some further objection, but Pelio silenced the archaeologist with a look. It was going to be hard to make even the most reasonable suggestions to the prince from now on. “Samadhom. Here!” Pelio called the watchbear out of the skiff. The animal landed heavily on the fur carpet and padded slowly across to his master’s feet.

Bre‘en shook his head in wonder as his eyes followed Sam across the floor. “An amazing animal!” His tone was almost conversational. “He’s protecting all three of you at once. We have no watchbears that Talented.” Yoninne looked out at the pale, staring faces. Witling slaves aside, anyone in that crowd could kill her and Pelio and Ajão in a fraction of a second—if it weren’t for Samadhom. And if it weren’t for the knife at Tru’ud’s throat, that crowd could beat them to death in scarcely more time. Bre’en must have read the expression on her face. “Without great good luck,” he said, “you would not now be alive. Such luck can’t hold, you—”

“I said to be quiet,” Pelio repeated, and Bre’en fell silent. “Get the magicians’ sphere onto yonder speedboat … . Quickly!”

King Tru‘ud gargled apoplectically, and in his rage admitted what the witlings had guessed: “You three … never will live for this.” The words were jumbled, both by anger and Tru’ud’s unfamiliarity with the language of the Summerkingdom. “Your death will be pain, much more pain than we gave your crew to die.”

L

eague after league, Bre‘en teleported the witlings and King Tru’ud northward, yet only the service buildings around the transit lakes seemed to change. Beyond their tiny boat’s windows, the sky remained a deep, cloudless blue. From thirty degrees off the glare-white horizon, the sun cast long, bluish shadows across the jumbled madness of the antarctic ice. It was way too bright to look at, though Yoninne’s wrist chron said it was early morning, Summerkingdom time. Here the night was more than one hundred days away.

For the moment, the Snowking’s forces were letting them proceed toward County Tsarang. If they could make it to that vassal state of Summer, they might yet have a chance to carry out the scheme that had once seemed the most dangerous part of Ajão’s plan, the scheme that would take them to Draere’s Island.

The boat they had stolen was small and its hull was strong, strong enough so they could safely skip every other transit lake along the road. They were making good progress even though they rested five or ten minutes between each jump: time for Bre’en to prepare for the next hop, time for Pelio to check the harnesses that bound the two hostages.

“I’m not taking any chances with our friends,” said Pelio. “No matter how highly trained, they can’t reng away from us as long as they’re tied down.”

Ajão said something about molecular bonding energies, but Leg-Wot already understood what Pelio meant: when Azhiri teleported, they took at least part of their surroundings with them; only Guildsmen had perfect control of the volume renged. In order to teleport themselves from the boat, Tru‘ud and Bre’en would have to cut through the straps that held them—an act that was far beyond the power of the Talent. Yoninne looked at Pelio with new respect. The trick was one that she—and perhaps Ajão—would not have thought of. For that matter, they wouldn’t be heading north right now if it weren’t for Pelio’s guts and initiative. Was it simply desperation that drove him, or had he been a man all along—all the time she treated him like a weakwilled adolescent?

“I think we’re being paced,” Ajão said abruptly, two jumps later.

“What?” said Pelio.

“Look around the lake. Several of those boats are awfully familiar.”

“Yes,” the prince said slowly. “And every lake is a bit more crowded than the last. I’ll wager the Snowmen messaged ahead, calling up every available army boat. In effect, we’re as tightly surrounded as we were back in their palace.” He grinned at Bre‘en and Tru’ud. “But it won’t do you any good. If they blast our boat, you’ll go down with it.” When the Snowmen did not respond he went on. “In a way I should be grateful to you two. You’ve given me a chance to prove I’m not completely helpless.”

“You needed the watchbear,” Bre’en pointed out glumly.