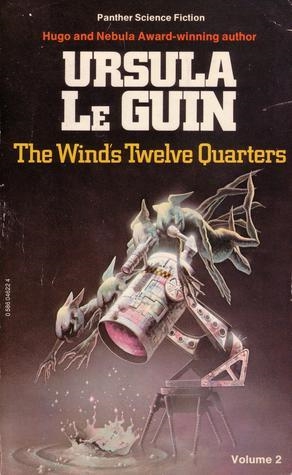

The wind's twelve quarters - vol 2

Read The wind's twelve quarters - vol 2 Online

Authors: Ursula K. Le Guin

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Short Stories, #Short stories; English, #Fiction

| Series: | The Earthsea Cycle [1] |

| Published: | 1978 |

| Rating: | *** |

| Tags: | Science Fiction, General, Short Stories, Short stories; English, Fiction |

EDITORIAL REVIEW:

The recipient of numerous literary prizes, including the National Book Award, the Kafka Award, and the Pushcart Prize, Ursula K. Le Guin is renowned for her lyrical writing, rich characters, and diverse worlds. The Wind's Twelve Quarters collects seventeen powerful stories, each with an introduction by the author, ranging from fantasy to intriguing scientific concepts, from medieval settings to the future.

Including an insightful foreword by Le Guin, describing her experience, her inspirations, and her approach to writing, this stunning collection explores human values, relationships, and survival, and showcases the myriad talents of one of the most provocative writers of our time.

Ursula Le Guin

The

Wind's Twelve Quarters

Volume

II

PANTHER

GRANADA PUBLISHING

London Toronto Sydney

New York

Published by Granada Publishing Limited in

Panther Books 1978

ISBN 0 586 04623 2

First published in Great Britain in one

volume under the title of

The Wind's Twelve

Quarters

by Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1976 Copyright ©

Ursula K. Le Guin 1975

Things

originally appeared under the title

The End

in

Orbit 6,

1970

A

Trip to the Head

originally

appeared in

Quark I,

1970

Vaster

than Empires and More Slow

originally

appeared in

New Dimensions 1,

1971

The

Stars Below

originally appeared in

Orbit 12,

1973

The Field of Vision

originally appeared in

Galaxy,

1973

Direction of the Road

originally appeared in

Orbit 14,

1974

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

originally appeared in

New Dimensions 3,

1973

The Day Before the

Revolution

originally appeared in

Galaxy,

1974

Granada Publishing Limited Frogmore, St

Albans, Herts AL2 2NF and

3 Upper James Street, London WiR 4BP

1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY

10020, USA

117 York Street, Sydney, NSW 2000,

Australia

100 Skyway Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M9W 3A6

Trio City, Coventry Street, Johannesburg

2001, South Africa

CML Centre, Queen & Wyndham Auckland 1,

New Zealand

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd, London, Reading and

Fakenham

Contents

Things

A

Trip to the Head

Vaster

than Empires and More Slow

The

Stars Below

The

Field of Vision

Direction

of the Road

The

Ones who Walk Away from Omelas

The

Day Before the Revolution

THINGS

Damon

Knight,

editor

mirabilis,

first

published this story in a volume of

Orbit,

under the

title 'The End'. I don't now remember how we arrived at it, but I suspect he

thought that 'Things' sounded too much like something you see on the television

at one

A.M.,

with purple tentacles. But I have

gone back to it because — at least

after

reading the

psychomyth — it puts the right emphasis. Things you use; things you possess,

and are possessed by; things you build with — bricks, words. You build houses

with them, and towns, and causeways. But the buildings fall, the causeways

cannot go all the way. There is an abyss, a gap, a last step to be taken.

On

the shore of the sea he stood looking out over the long foam-lines far where

vague the Islands lifted or were guessed. There, he said to the sea, there lies

my kingdom. The sea said to him what the sea says to everybody. As evening

moved from behind his back across the water the foam-lines paled and the wind

fell, and very far in the west shone a star perhaps, perhaps a light, or his

desire for a light.

He

climbed the streets of his town again in late dusk. The shops and huts of his

neighbors were looking empty now, cleared out, cleaned up, packed away in

preparation for the end. Most of the people were up at the Weeping in

Heights-Hall or down with the Ragers in the fields. But Lif had not been able

to clear out and clean up; his wares and belongings were too heavy to throw

away, too hard to break, too dull to burn. Only centuries could waste them.

Wherever they were piled or dropped or thrown they formed what might have been,

or seemed to be, or yet might be, a city. So he had not tried to get rid of his

things. His yard was still stacked and piled with bricks, thousands and

thousands of bricks of his own making. The kiln stood cold but ready, the

barrels of clay and dry mortar and lime, the hods and barrows and trowels of

his trade, everything was there. One of the fellows from Scriveners Lane had

asked sneering, Going to build a brick wall and hide behind it when that old

end comes, man?

Another

neighbor on his way up to the Heights-Hall gazed a while at those stacks and

heaps and loads and mounds of well-shaped, well-baked bricks all a soft reddish

gold in the gold of the afternoon sun, and sighed at last with the weight of

them on his heart: Things, things! Free yourself of things, Lif, from the

weight that drags you down! Come with us, above the ending world!

Lif

had picked up a brick from the heap and put it in place on the stack and smiled

in embarrassment. When they were all past he had gone neither up to the Hall

nor out to help wreck the fields and kill the animals, but down to the beach,

the end of the ending world, beyond which lay only water. Now back in his

brickyard hut with the smell of salt in his clothes and his face hot with the

sea wind, he still felt neither the Ragers' laughing and wrecking despair nor

the soaring and weeping despair of the communicants of the Heights; he felt

empty; he felt hungry. He was a heavy little man and the sea wind at the

world's edge had blown at him all evening without moving him at all.

Hey

Lif! said the widow from Weavers Lane, which crossed his street a few houses

down, —I saw you coming up the street, and never another soul since sunset, and

getting dark, and quieter than ... She did not say what the town was quieter

than, but went on, Have you had your supper? I was about to take my roast out

of the oven, and the little one and I will never eat up all that meat before

the end comes, no doubt, and I hate to see good meat go to waste.

Well

thank you very much, says Lif, putting on his coat again; and they went down

Masons Lane to Weavers Lane through the dark and the wind sweeping up steep

streets from the sea. In the widow's lamplit house Lif played with her baby,

the last born in the town, a little fat boy just learning how to stand up. Lif

stood him up and he laughed and fell over, while the widow set out bread and

hot meat on the table of heavy woven cane. They sat to eat, even the baby, who

worked with four teeth at a hard hunk of bread. —How is it you're not up on the

Hill or in the fields? asked Lif, and the widow replied as if the answer

sufficed to her mind, Oh, I have the baby.

Lif

looked around the little house which her husband, who had been one of Lif's

bricklayers, had built. —This is good, he said. I haven't tasted meat since

last year some time.

I

know, I know! No houses being built any more.

Not

a one, he said. Not a wall nor a henhouse, not even repairs. But your weaving,

that's still wanted?

Yes;

some of them want new clothes right up to the end. This meat I bought from the

Ragers that slaughtered all my lord's flocks, and I paid with the money I got

for a piece of fine linen I wove for my lord's daughter's gown that she wants

to wear at the end! The widow gave a little derisive, sympathetic snort, and

went on: But now there's no flax, and scarcely any wool. No more to spin, no

more to weave. The fields burnt and the flocks dead.

Yes,

said Lif, eating the good roast meat. Bad times, he said, the worst times.

And

now, the widow went on, where's bread to come from, with the fields burnt? And

water, now they're poisoning the wells? I sound like the Weepers up there,

don't I? Help yourself, Lif. Spring lamb's the finest meat in the world, my man

always said, till autumn came and then he'd say roast pork's the finest meat in

the world. Come on now, give yourself a proper slice...

That

night in his hut in the brickyard Lif dreamed. Usually he slept as still as the

bricks themselves but this night he drifted and floated in dream all night to

the Islands, and when he woke they were no longer a wish or a guess: like a

star as daylight darkens they had become certain, he knew them. But what, in

his dream, had borne him over the water? He had not flown, he had not walked,

he had not gone underwater like the fish; yet he had come across the grey-green

plains and wind-moved hillocks of the sea to the Islands, he had heard voices

call, and seen the lights of towns.

He

set his mind to think how a man could ride on water. He thought of how grass

floats on streams, and saw how one might make a sort of mat of woven cane and

lie on it pushing with one's hands: but the great canebrakes were still

smoldering down by the stream, and the piles of withies at the basketmaker's

had all been burnt. On the Islands in his dream he had seen canes or grasses

half a hundred feet high, with brown stems thicker than his arms could reach

round, and a world of green leaves spread sunward from the thousand outreaching

twigs. On those stems a man might ride over the sea. But no such plants grew in

his country nor ever had; though in the Heights-Hall was a knife-handle made of

a dull brown stuff, said to come from a plant that grew in some other land,

called wood. But he could not ride across the bellowing sea on a knife-handle.

Greased

hides might float; but the tanners had been idle now for weeks, there were no

hides for sale. He might as well stop looking about for any help. He carried

his barrow and his largest hod down to the beach that white windy morning and

laid them in the still water of a lagoon. Indeed they floated, deep in the

water, but when he leaned even the weight of one hand on them they tipped,

filled, sank. They were too light, he thought.

He

went back up the cliff and through the streets, loaded the barrow with useless

well-made bricks, and wheeled a hard load down. As so few children had been

born these last years there was no young curiosity about to ask him what he was

doing, though a Rager or two, groggy from last night's wreckfest, glanced

sidelong at him from a dark doorway through the brightness of the air. All that

day he brought down bricks and the makings of mortar, and the next day, though

he had not had the dream again, he began to lay his bricks there on the blustering

beach of March with rain and sand handy in great quantities to set his cement.

He built a little brick dome, upside down, oval with pointed ends like a fish,

all of a single course of bricks laid spiral very cunningly. If a cupful or a

barrowful of air would float, would not a brick domeful? And it would be

strong. But when the mortar was set, and straining his broad back he overturned

the dome and pushed it into the cream of the breakers, it dug deeper and deeper

into the wet sand, burrowing down like a clam or a sand flea. The waves filled

it, and refilled it when he tipped it empty, and at last a green-shouldered

breaker caught it with its white dragging backpull, rolled it over, smashed it

back into its elemental bricks and sank them in the restless sodden sand. There

stood Lif wet to the neck and wiping salt spray out of his eyes. Nothing lay

westward on the sea but wavewrack and rainclouds. But they were there. He knew

them, with their great grasses ten times a man's height, their wild golden

fields raked by the sea wind, their white towns, their white-crowned hills

above the sea; and the voices of shepherds called on the hills.

I'm

a builder, not a floater, said Lif after he had considered his stupidity from

all sides. And he came doggedly out of the water and up the cliff-side path and

through the rainy streets to get another barrowload of bricks.

Free

for the first time in a week for his fool dream of floating, he noticed now

that Leather Street seemed deserted. The tannery was rubbishy and vacant. The

craftsmen's shops lay like a row of little black gaping mouths, and the

sleeping-room windows above them were blind. At the end of the lane an old

cobbler was burning, with a terrible stench, a small heap of new shoes never

worn. Beside him a donkey waited, saddled, flicking its ears at the stinking

smoke.