The Willows in Winter (27 page)

Read The Willows in Winter Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson

Tags: #Young Adult, #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

“Forgot’ he whispered once again, and wept.

Yet Toad was not forgotten at all. His name, for those few days after

his capture and before other more salacious news displaced him from the scandal

sheets and daily papers, was on every lip and elicited much excitement. More

than that, so serious were the implications of his suspected crimes considered

to be, so profound the possible threat to society, so very grave the threat to

national security if such a trend continued, that questions were asked not only

in Parliament and Privy Council, but in the Mansion House and in the Royal

Courts of Justice too.

All of which meant that the matter of the

infamous Mr Toad attracted the attentions not just of the popular press, but

also of

The Times,

in which it was granted a single paragraph of type,

somewhere below the Agricultural News.

Now, it was many a year since a newspaper from

the Town had found its way anywhere near the inhabitants of bank and river,

meadows and

Wild

Wood. Indeed, the only newspaper most

had ever seen, and those were the rare and lucky ones who had at some time in

their lives won the confidence of the Badger sufficiently to catch a glimpse of

a copy he had framed on his wall, was that which carried the report of the Jubilee,

which was back in his great-grandfather’s time.

But somehow, some weeks after Toad’s

incarceration, a copy of

The Times,

or rather that fell paragraph of

print concerning Toad, found its way to the Badger, who, having read it,

summoned the Mole and the Rat forthwith.

“My friends,” he said gravely, “I have bad

news.”

“It

is

Toad,” said the Mole, spontaneous

tears coming to his eyes as he saw the Badger raise the newspaper up to read

aloud from it, ‘just as I said on the way here!”

He addressed this to the Water Rat, who sighed

and said, “I fear it must be,” and they both sat down disconsolately.

“It is indeed’ said the Badger, not quite sensitive

to his friends’ assumptions, and distress. “It certainly is.”

“Read it,” said the practical Rat.

“I was about to’ said the Badger. What he read

out was printed under the forbidding headline “TOAD ARRESTED” which was

followed by a second headline: “FULL CHARGES TO BE BROUGHT WHEN ALL HIS CRIMES

ARE KNOWN”.

The paragraph succinctly set out the long list of wretched crimes and

felonies which all the circumstantial evidence pointed to Toad having

committed, and said much else besides. It spoke of weddings ruined, of brides

distraught, of Lords and Bishops, and the police, and it exposed the attempted

abduction of an innocent wife, a crime of the lowest and most scurrilous kind.

It left no doubt that Toad was guilty, very guilty indeed, and the only

question remaining was how exemplary and how savage must his sentencing be.

“What does it mean?” asked the Mole, who did

not understand at all.

“It means that Toad’s got himself in a mess again,”

said the Rat reasonably. “But at least he’s not — he hasn’t passed away as we

feared, Mole.”

“It means that it is a mess Toad is unlikely to

get out of this time,” added the Badger.

“Is there nothing we can do?”

“Against such evidence, when Lords and Bishops

and police and wronged wives have been invoked?” said the Badger. “I doubt it

very much indeed. I suppose that a successful plea might perhaps mean that

rather than being quartered, he might be merely hanged.”

“O my!” said the Mole softly. “I feel quite

unwell.” They sat in silence, ruminating sombrely, for this was so far out of

their domain that they saw no way to help their errant friend.

“One thing’s rum about it all,” said the Rat

last. “In fact, I would call it peculiar.”

“What’s that?” said the Mole almost

indifferently, for what was the point of musing on it when nothing could be

done?

“There’s no mention of the flying machine, is

there? That’s right, isn’t it, Badger?”

Badger sat up, suddenly a little more alert.

“You

are

right,” he said, examining the

newspaper once more. “That is most observant of you and it is certainly, as you

put it, very rum indeed. I must think.”

The Badger began to think very hard and went

into so profound and impenetrable a silence that the Rat and the Mole eventually

left him to it, and set off towards Otter’s house.

It was the time of year when winter seemed

almost done, but spring had not yet quite shown its face. Snowdrops and the

catkins of alder are all very well, and certainly signal the stirring of

something or other, but what animals like the Rat and the Mole really want to

see and feel is bright warm sunshine on the budding branches, and what they

yearn to hear and smell is the rushing song of the smaller birds busy about

their broods, and the first balmy scents of the bluebells through the wood, and

the violet on the banks.

Then, too, both knew full well that winter was

quite capable of asserting itself again, and bringing upon them all its cold

and rain, winds and hail, as if to say, “I’m soon going for quite a time, but

this is just to remind you that one day I shall be back.”

“Ratty’ said the Mole, as they drew near the

Otter’s place, “do you think there’s any hope at all for Toad?

Or should we try now to forget him, remembering him sometimes only

in our wishes and prayers?”

Mole said this so gently, and in so caring a

way, that

it almost brought tears to the sturdy Water Rat’s

eyes. Yet, what hope could there be, given the mess Toad had got himself into?

Why, not even Badger —”I think,” said the Water Rat cautiously, “that if

there’s anyone hereabouts who could find a way out for Toad, however slim and

slight it might be, it would be Badger. I don’t know what he was thinking about

when we left him, but that he

was

thinking there can be no doubt. We

both know that when Badger thinks like that things tend to happen. So we’ll

just have to wait and hope. Now, let’s see if Otter can cheer us up with a warm

drink and better news than we’ve had so far today?

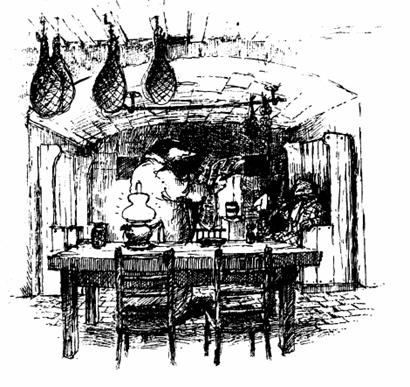

Badger certainly did think, hard and long,

barely moving from the chair that the Rat and the Mole had left him in till

nightfall, when he rose slowly and stiffly, stretched and, lighting a candle,

went into his study and sat down at his desk.

It was many years since he had been moved to

write a letter, and never before had he felt sufficiently moved by the

importance and injustice of a matter, that he must address his letter to that

most august and revered personage, The Editor of

The Times.

But so he did, marking the envelope clearly in

his bold hand: PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL, NOT FOR PUBLICATION.

Such was the result of his thoughts, and when morning came he summoned

to his presence the swiftest and fleetest of the stoats, and began to address

him thus:

“We have not always seen eye to eye, you and I.

Nor can I say that in the matter of the promised high tea in these modest rooms

of mine I have behaved with the speed I should have. That can be rectified, and

it will be. But there are some things harder to rectify, before which, when we

face them, we must all forget our differences and fight for the common good.”

“Yes?” said the stoat dubiously. “What

particular

thing have

you in mind?”

“A grave miscarriage of justice,” said the

Badger. “Now, listen to me. You will take this letter and, using all your

cunning and experience of the Wide World beyond the river, you will deliver it

as addressed.”

“What’s it all about?” asked the unwilling

stoat. “Ask not what it’s about, but who it’s about,” said the Badger. “It is

about Toad of Toad Hall.”

“Ah, yes — Toad,” said the stoat, not without a

certain respect and awe in his voice, which Badger did not miss, nor was

surprised by. Toad’s escapades held a sorry fascination for the stoats and

weasels, which one might expect, given their general low character and untrustworthy

nature. Like with like. But at a time like this, needs

must,

and the Badger needed stoats, and this one in particular.

“Will I, too, get an invitation to this tea

you’re having?” he asked.

The Badger smiled slightly and reached behind

him to his mantelpiece, from where he took down a stack of elaborately printed

cards on which in the most

scrolly

and embossed of

lettering shone and shimmered the word INVITATION.

“One of these shall be yours,” said the Badger,

“if you take this letter and deliver it as I ask.”

The stoat’s eyes glittered and glistened with

social greed and expectation.

“Personally inscribed by me with your own name,

added the Badger.

“And shall I be sitting on your right-hand

side?” asked the stoat in a soft insinuating voice.

Badger blinked at the boldness of it, bit back

the words he might normally have spoken, and said, with some effort, “You

shall!”

The stoat did no more than sigh and reach

forward to take the letter, before he turned and was off on his mission.

“I can do no more,” whispered the Badger to

himself

, shaking his head sadly, for he cherished little

hope that his words would hold much sway in the offices and corridors of the

most influential in the land. “We can only hope —Hope was very far from Toad’s

mind some days later when the heavy door of his cell was heaved open, and his

gaoler, along with three of his largest colleagues, strode in.

They chained and manacled their dangerous

charge once more, leaving him only sufficient movement to shamble and struggle

along the ancient passageways of his place of confinement, and then up its

endless stone steps and stairways, which he saw now were worn and slippery with

the downward passage of so many long-forgotten criminals.

“Not that way!” cried his pessimistic friend,

grasping Toad’s arm and directing him away from the especially grim and

oppressive corridor into which his laboured steps seemed automatically to have

led him. At its end was a set of bars beyond which was an archway leading out

into the open air, where, caught by the first sunlight Toad had seen since his

incarceration, was what was unmistakably a hangman’s noose, swaying invitingly

in the morning breeze.

Toad let out a gasp of dismay, but his gaoler

reassured him. “It’s all right, sir, you’re not on today’s list.”

“List?” faltered Toad.

“Of the finally and irrecoverably condemned.”

“Where am I being taken?” gasped Toad, sweat

breaking out on his brow.

“To your Preliminary and Final Hearing,” said

the gaoler, urging him on up a last few steps.

“Preliminary and Final!

Isn’t there a Court of Appeal?”

asked Toad.

“That’s been and gone in your case, sir. The

Court you’re going to is as

Final

as they come. So

final in fact that it’s almost pointless to go through its doors, but one never

knows, there might be an upset.”

“An upset!” cried Toad, desperately grasping at

straws. “There has been an upset before then?

When?”

“In 1376, sir, in the case of Saint

Simon the Innocent.

That was the last time,” said the gaoler dolefully.

Each dragging step that Toad now took rang out

about him like the tolling centuries and he dared not even raise his eyes when,

brought finally to an immense oak door, the gaoler knocked upon it.

There was a long wait, during which Toad could

hear his own heart beat, before a thin voice called out from within, “Bring in

the prisoner!”

The door opened and Toad was led forward into

an immense and echoing chamber, whose ancient arched windows rose before him

and sent down such shafts of light into the dusty interior that for a moment he

could see nothing more. But as his eyes adjusted to the light he saw that set

beneath the windows, lengthways, was a vast oaken council table, on whose far

side were ranged seven great high chairs, within whose imposing confines sat

seven imposing figures,

berobed

, bewigged, long of

face, cold of eye, aquiline of nostril, and judgemental of general disposition

and effect.