The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (88 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

It’s been said by modern environmentalists that Roosevelt had a conflict of loyalties in the West between pro-growth policies like the Reclamation Act and pro-preservation policies like saving the redwoods. This is true. Basically, he wanted to have it both ways. Starting with Roosevelt Dam on the Salt River near Phoenix, Arizona, virtually every major waterway in the West was altered by environmentally destructive engineering projects that T.R. OK’d. Roosevelt saw himself as the master preservationist but also beamed as a master builder. Save the Grand Canyon while building the Roosevelt Dam—that was his conservationist policy. To Roosevelt, conservation could be another form of conquest; development

and

protection working in harmony for an Edenic civilization. When push came to shove, economic growth often took precedence over his preservationism. He made his decisions case by case. Conservation as big business was regularly given precedence over conservation as protection—but there were many exceptions. Over the decades, this has made him something of a bogeyman to the Sierra Club types. Following President Dwight Eisenhower’s speech about the industrial-military complex in 1961, for example, Roosevelt’s Reclamation Service was denounced by anti-war enviromentalists like Dave Brower and Wallace Stesner as scientific capitalism run amok. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, historians lacerated Roosevelt for his imperialistic views, which they equated with the policies that had led to Vietnam. And, unlike John Wesley Powell, a generation of enviromental historians led by Donald Worster complained, Roosevelt liked

big

dams—

big

everything, including a

big

intrusive federal government.

But the anti-Roosevelt critics went too far. President Lyndon Johnson’s entire “New Conservationism” of the 1960s was purposefully mod

eled on ideals T.R. had first propounded. And modern environmentalists were aware that Roosevelt had also liked

big

national forests: in 1908, for example, he created the Tongass National Forest, which stretched over 500 miles from north to south in Alaska and included more than 11,000 miles of rugged coastline (a figure equal to nearly 50 percent of the entire coastline of the lower forty-eight.)

94

As Roosevelt’s attitude toward the redwoods showed during this California trip, he was emotionally a forest preservationist while politically a utilitarian conservationist. It was the right combination for his times. But never for a moment did Roosevelt purposely seek to abuse the American West in any way. But such sincerity had its limits: Roosevelt lacked self-awareness regarding his very real contradiction, his insistence on

bigness

wrought on the western landscape. Yet, always, he wanted to create model cities surrounded by greenbelts of wilderness. He was a promoter of

sustainability

before the concept came into vogue during the Clinton era of the 1990s.

Journalists throughout California commented on how hard Roosevelt was working during his two-week statewide tour to inject conservation into the political bloodstream. The

Los Angeles Times

wrote of his “strenuosity,” and the

Oakland Tribune

called him a “drayhorse working every hour.”

95

And although she was not involved in policy, the first lady did participate in tree (or at least shrubbery) preservation in the East. Edith Roosevelt was making news by objecting publicly when remodelers at the White House wanted to remove more than seventy bushes from the terrace. She had grown fond of the shrubbery and wanted it to stay put. Even when she was told that the bushes would be carefully removed and replanted in New Jersey, she insisted that they be left unmarred and unmoved.

VII

After shaking so many hands, Roosevelt needed an outdoor adventure in the Sierras. Shortly after midnight on May 15 he left San Francisco for Yosemite Valley with an honorary doctorate from the University of California–Berkeley in hand. Accompanying him was his delegation, which included the Sierra Club’s president, John Muir; Governor George C. Pardee of California; and Benjamin Wheeler, president of the University of California–Berkeley. The party enjoyed the scenic mountain ramparts en route, and then Roosevelt’s train stopped at Raymond, the railroad depot closest to Yosemite. Three previous U.S. presidents had visited Yosemite—James Garfield in 1875, Ulysses S. Grant in 1879, and Rutherford B. Hayes in 1885—but not while in office, so Roosevelt’s visit

was a first. And instead of coming to the national park merely as a political gesture, Roosevelt planned to study Yosemite as a naturalist—hence Muir’s presence at his side. “Of course of all the people in the world,” Roosevelt said, “[Muir] was the one with whom it was best worth while thus to see the Yosemite.”

96

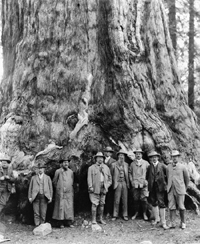

Roosevelt and Muir, taking a buggy, headed straight for the “big tree” section—Mariposa Grove, where some of the oldest redwoods in California grew. A photograph was snapped of them driving through the rather touristy Wawona Tunnel Tree (a towering sequoia that fell in 1969). Mariposa Grove wasn’t yet officially part of Yosemite National Park in 1903 but Roosevelt hoped it might soon be. As the

New York Times

reported, Roosevelt and Muir arrived in Mariposa Grove on a bright, perfectly clear day, had lunch, and then wandered off together. Walking around the huge circumferences of the redwoods with Muir, staring upward more than 250 feet to see the top branches, Roosevelt was in his element.

97

While studying the famous “Grizzly Giant,” the president blurted out, intensely, that this was “the greatest forest site” he had ever seen.

98

The naturalist Henry Fairfield Osborn had said of Muir that he “wrote about trees as no one else in the whole history of trees, chiefly because he loved them as he loved men and women.”

99

Now Roosevelt understood what Muir had been so rhapsodical about over many years. “There are the big trees, Mr. Roosevelt,” Muir excitedly said. “Mr. Muir,” Roosevelt said with a smile, “it is good to be with you.”

100

Muir had an ethereal quality and his erudition was simultaneously bold and profound. Roosevelt immediately admired him. Muir’s eyes were deep blue, his hair was ginger-reddish, and his attitude was life-affirming. While Roosevelt thought in terms of Americanism in nature, Muir thought about the planet in peril. He had even once titled a journal: “John Muir, Earth-planet, Universe.” Having read all of Muir’s works, and realizing that the great naturalist had spent thirty years studying the trees, rocks, canyons, falls, and glaciers of Yosemite, Roosevelt felt like a student arriving at an academy. Furthermore, Merriam had advised Roosevelt to camp with his friend Muir; he predicted it would be one of the memorable moments of his life.

101

Because no authoritative account was ever written of Roosevelt and Muir’s trip of 1903, it has been pieced together by varied sources over the years. Together, Roosevelt and Muir did explore the park for three days and two nights. Even though Roosevelt was officially booked at the Glacier Point Hotel, he instead camped with Muir in the great outdoors. They would drink in the fresh air, survey the ridgelines, and listen to each

other’s voice echoing out over the Yosemity Valley. The U.S. Army oversaw the park and was extremely accommodating of Roosevelt’s needs. But Roosevelt wanted lots of privacy. Waving a captain and thirty cavalrymen away with a “God bless you,” Roosevelt made it clear that he wanted to be alone with Muir among the thickset trees and trailside brush. Only the guides Charlie Leidig and Archie Leanor and the U.S. Army climber Jacker Alder were allowed to untie the saddlehorn rope to be part of the presidential entourage when a hike was in order.

102

The president treated Muir as his absolute equal throughout the Yosemite adventure. Roosevelt and Muir were both mavericks and shared a strong, rare bond: appreciation of nature. “[Muir] was emphatically a good citizen,” Roosevelt noted. “Not only are his books delightful, not only is he the author to whom all men turn when they think of the Sierras and northern glaciers, and the giant trees of the California slope, but he was also—what few nature lovers are—a man able to influence contemporary thought and action on the subjects to which he had devoted his life. He was a great factor in influencing the thought of California and the thought of the entire country so as to secure the preservation of those great natural phenomena—wonderful canyons, giant trees, slopes of flower-spangled hillsides—which make California a veritable Garden of the Lord.”

103

Leaving Mariposa Grove, the Roosevelt party headed to Yosemite’s south entrance by carriage, through a handsome glen. As he got out of the carriage, Roosevelt asked for his valise—he didn’t like being separated from his personal belongings. When told that the Yosemite Park Commission had brought his baggage to a banquet lunch, he grew enraged. “Get it!,” he shouted. According to Muir the two words, barked with an authoritarian air, were like bullets being fired.

104

Although reporters sometimes portrayed Muir as a misanthrope, he made friends quickly. There was never a moment of awkwardness with Roosevelt. Really, the only strange thing about Muir was that he had never once shaved in his life.

105

On May 15 Roosevelt and Muir mounted horses and trotted off into the vast sequoia lands near the Sunset Tree. The strength and beauty of Yosemite were undeniable. Somehow, there was a summery fragrance in the air even though there was snow. Roosevelt praised the cinnamon-colored sequoias’ enduring beauty. Roosevelt recalled in

An Autobiography

, “The majestic trunks, beautiful in color and in symmetry, rose round us like the pillars of a mightier cathedral than ever was conceived even by the fervor of the Middle Ages. Hermit thrushes sang beautifully in the

evening, and again, with a burst of wonderful music, at dawn.”

106

That evening they built a campfire; continually feeding it wood, they talked until the fire drew down to coals. It was the most famous campfire ever in the annals of the conservation movement. Over the popping and crackling logs Roosevelt and Muir talked about

forest good

and slept soundly without a tent.

At sunrise on May 16 Roosevelt and Muir decided to forgo the day’s official itinerary and ride horseback by themselves through the melting snow along an old Indian trail to Glacier Point. There is a marvelous photograph of Roosevelt and Muir standing on a ledgerock overlooking the valley, a respectable 3,200 feet high, with Yosemite Falls thundering at their backs. On close inspection, patches of diminishing snow are noticeable on the thawed ground. Roosevelt looks ready to draw a weapon; Muir is seemingly relaxed, hands behind his back. Over the decades this photograph has become an icon promoting American national parks, for the Sierra Club and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service alike. It has been reproduced on book jackets and in magazines. According to historian Donald Worster of the University of Kansas, Roosevelt and Muir had

good reason to look so satisfied in each other’s august company. “They have just agreed that ownership of the much-abused valley below should revert to the federal government and become part of Yosemite Park,” he notes in an analysis of the photograph. “Politically, they have forged a formidable alliance on behalf of nature.”

107

Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir at Mariposa Grove in California.

T.R. and Muir at Mariposa Grove. β

(Courtesy of the National Park Service)

Through a blinding snowstorm, Roosevelt and Muir footslogged to Sentinel Dome, a few miles from Glacier Point Hotel. Five feet of snow already lay on the ground. A little base camp was chosen sheltered from the frost heave and glaze ice.

108

Muir built a marvelous bonfire that second evening and made a bed of ferns and cedar boughs. “Watch this,” Muir said. Grabbing a flaming branch from the campfire he lit a dead pine tree on a ledge. With a roar, as if a squirt of gasoline had been administered, the flame shot up the dead branches. Suddenly Muir did a Scottish jig around the pine torch. Such ritualistic acts were right up Roosevelt’s alley. Leaping to his feet he hopped around the flaming tree, shouting “Hurrah!” over and over again into the night sky. “That’s a candle,” Roosevelt told Muir, “it took 500 years to make. Hurrah for Yosemite! Mr. Muir.”

109

Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, on April 21, 1838. When he was eleven his family emigrated from Glasgow to Marquette County, Wisconsin. Throughout his adolescence he toiled on his father’s farm and tinkered with clocks, barometers, hydrometers, and table saws. When he was eighteen he almost died from “choke damp” while digging a well. During the Civil War he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he invented a study desk that retrieved a book, held it stationary for hours, then automatically replaced it with a different volume. It was a weird contraption, but it indicates how enthusiastic a bibliophile Muir was. With eagerness and diligence Muir read about Henry David Thoreau’s rejection of bourgeois society and Robert Burns’s revolutionary democracy. The sage Ralph Waldo Emerson, as an old man, encountered Muir and deemed him “one of my men,” a true-blue Transcendentalist.

110