The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (80 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Few wildlife enthusiasts could quarrel with the good intentions of Chapman’s expansive, habitat-conscious nature photography. Most, however, as the modest sales of

Bird Studies with a Camera

indicated, probably still preferred one of the approximately 430 drawings in Audubon’s

Birds of America

to Chapman’s photograph of a puffin’s burrow (minus the bird). And their reasoning wasn’t simply a matter of aesthetic pleasure. Real hunters, not the riffraff who slaughtered nesting birds for money, found something missing from Chapman’s philosophy—

the chase

. To Chapman’s everlasting credit, he bravely confronted the “chase issue” in his proactive book through a combination of salesmanship (with regard to photography) and ridicule (of plume hunting). The essential message

of

Bird Studies with a Camera

was something like “Real men don’t kill little helpless uneatable things for sport.” But true outdoorsmen, like those responsible for Adirondack Park and Crater Lake National Park, didn’t kill shorebirds or songbirds anyway. In some ways Chapman was preaching to the converted. “I can affirm that there is a fascination about the hunting of wild animals with a camera as far ahead of the pleasure to be derived from their pursuit with shotgun or rifle as the sport found in shooting Quail is beyond that of breaking clay ‘Pigeons’” he wrote. “Continuing the comparison, from a sportsman’s standpoint, hunting with a camera is the highest development of man’s inherent love of the chase.”

26

That argument seemed reasonable enough. But it wasn’t convincing to true-blue hunters: they refused to feel ashamed of preferring taxidermy to the darkroom. You could almost hear the dismissive grumble from late-nineteenth-century sportsmen piqued about Chapman’s advocacy of the camera. Chapman’s argument, they believed, was a ruse, like comparing apples and oranges. About a third of the way into his book—at which point his ideas were already rejected by most sportsmen—the high-minded Chapman lowered the boom regarding a wildlife protection. “The killing of a bird with a gun,” he wrote, “seems little short of murder after one has attempted to capture its image with a lens.” With slow-boiling rage he continued to challenge the very manhood of “so-called

true sportsmen,” arguing that rejoicing over a trophy bag of “mutilated flesh and feathers” of nongame birds was utterly obscene.

27

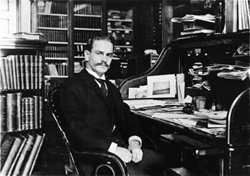

The ornithologist Frank M. Chapman of the American Museum of Natural History did more to save Florida’s bird rookeries than anyone else in American history. He successfully lobbied President Roosevelt to create federal bird reservations.

Frank M. Chapman. (

Courtesy of the American Museum of National History

)

Reading

Bird Studies

was an inspiration for Kroegel. He quickly recognized that Chapman was a kindred spirit like none other, a self-taught ornithologist of deep learning and forbearance. They were, to his mind, a fraternity of two. All the brown pelicans’ habits Kroegel had observed daily from his homestead at Indian River were extolled in gorgeous naturalist prose in Chapman’s

Bird Studies

. “No traveler ever entered the gates of a foreign city with greater expectancy than I felt as I stepped from my boat on the muddy edge of this City of the Pelicans,” Chapman wrote. “The old birds, without a word of protest, deserted their homes, leaving their eggs and young at my mercy. But the young were as abusive and threatening as their parents were silent and unresisting. Some were on the ground, others in the bushy mangroves, some were coming from the egg, others were learning to fly; but one and all—in a chorus of croaks, barks, and screams, which rings in my ears whenever I think of the experience—united in demanding that I leave town.”

28

There—in precise ornithological prose—was Kroegel’s daily reason for skippering a boat around Pelican Island but seldom walking on the sanctuary. In Chapman he had found his own highly personal Thoreau. Chapman had written that brown pelicans had a “dignified way,” that the island was their “metropolis.” Kroegel liked that kind of descriptive imagery. After spending four full days on the roost, Chapman wrote, “During no hour of the twenty-four did silence reign.” The sharp-eyed New Yorker even knew that pelicans liked to flap their broad wings for ten or eleven straight beats. As far as Kroegel knew, nobody, besides himself, had ever done that arithmetic before. And therein is what floored him about

Bird Studies

. Chapman had done the math. The esteemed ornithologist had counted 251 nests during his stay in March 1898 and then broke the total down as follows:

55 nests with 1 egg each

63 " " 2 eggs " "

23 " " 3 eggs " "

63 " " 1 young each;

46 " " 2 young each;

Such field calculations enthralled Kroegel. He thought Chapman was spot-on with his estimate of 2,736 pelicans for the island. The famous ornithologist had also captured the glory of what it

sounded like

to hear a

pelican hatch, calling the young chicks’ first noise on earth a “choking bark.”

29

Besides writing about Pelican Island in

Bird Studies

, Chapman, under Roosevelt’s urging, gave public presentations with stereopticon slides in Boston, Washington, D.C., and New York, bringing the plight of Florida’s tidewater rookeries to a wider audience. He even kept a “bird count” of species he saw women wearing as apparel on Fifth Avenue. In one hour of one day in 1885, he identified 174 birds of forty different species adorning ladies’ hats. In his lectures, he would verbally confront such women for indulging a penchant for precious feathers. Chapman implored them to switch over to domesticated ostrich feathers, which could be plucked or collected without hurting the bird. He had done so himself at an ostrich farm in Florida. The feathers from these flightless birds—celebrated for their fleet-footedness by ancient Egyptian kings—were gorgeous, ideal for hats, decor, and masks. If a woman really wanted to strike a theatrical pose, Chapman would say, then she should don an ostrich feather.

IV

One afternoon Kroegel actually got a chance to meet the mild-mannered, owlish Chapman, who resided at the Oak Lodge in Micco, Florida. The ten-bedroom boardinghouse—situated along the “soothing breeze” belt of the Atlantic Ocean between Melbourne and Vero Beach—was run by Mrs. Frances Latham (known as Ma Latham), a die-hard bird enthusiast who prayed that Pelican Island would someday become a sanctuary. Chapman called Ma Latham a “born naturalist” overflowing with “great enthusiasm and energy” for saving wild Florida.

30

“To me she was a combination of mother and guide,” Chapman recalled, “and when…my search for

Neofiber

[round-tailed muskrat] was rewarded I believe that her pleasure and excitement equaled my own…I never lacked for a sharer of my joys.”

31

Salty, no-nonsense, and razor smart, Ma Latham often collected sea turtle eggs to give to herpetologists; once, she collected a full series of loggerhead embryos acquired on daily seashore walks for sixty days.

32

She was among the first U.S. naturalists to truly study the egg-burying habits of loggerheads along the east coast of Florida in what is now the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge. With her sun-wrinkled face and no-frills pioneer-style dresses, she epitomized hardscrabble Florida slowly entering the automobile age. Turning her back on the Florida gold rush for feathers and eggs, she challenged all plumers and eggers with a cold glare that caused them to cast their eyes downward in guilt.

By the time Roosevelt was president, Oak Lodge had become a way

station for Ivy League–trained scientists, naturalists, and botanists enthralled to find more than 2,000 varieties of plants just a short walk away. After an arduous day of collecting, the wildlife lovers would retreat to the lodge at dusk to watch the sun set over the Indian River Lagoon. Over drinks Ma Latham regaled Chapman and the visiting naturalists with offbeat stories about Florida panthers and black bears, which roamed beaches looking for sea turtle eggs to dig up. Abhorrence, however, came easily to Ma Latham when she thought nature was being violated. For example, she strongly opposed haul-seining, a destructive fishing method in which dories were launched into the Atlantic surf with a long net that was then dragged onto the beach by oxen harnessed to a rope. After such intensive labor it was bounty time for the fishermen. However, Ma Latham believed that such unrestricted harvesting would eventually wipe out the tarpon, red snapper, and other fish species. Over time Chapman had learned to love everything about Ma Latham, as did other distinguished New York conservationists such as William Dutcher, William Beebe, Arthur Cleveland Bent, George Shiras III, Outram Bangs, John Burroughs, Louis Aggasiz Fuertes, William T. Hornaday, Herbert K. Job, and Abbott Thayer.

33

So it was that in 1900, sensing the main chance to save Pelican Island, Kroegel, a friend of Ma Latham, met with Chapman. She had sent word to Kroegel by boat mail that the great New York ornithologist had arrived. It was just over six miles from Sebastian to Micco, and Kroegel made the trek in record time. The meeting apparently went exceedingly well. For all of Chapman’s urbane book knowledge of birds, Kroegel actually

lived

amid the cornucopia of rookeries year-round. As a field naturalist Kroegel had studied pelicans longer and harder than Chapman. For obvious reasons Chapman was deeply impressed with the self-taught Kroegel. Certainly the former Wall Street financier and the swamp accordionist weren’t cut from the same socioeconomic cloth. But their shared love of birds made them a formidable united front. Together they constituted a sort of two-man Rough Riders cavalry unit—one from the backwoods, the other from the eastern elite—both determined to save the Pelican Island ecosystem. One can imagine them sitting in the amethyst twilight at Oak Lodge among myrtle oaks—a roaring campfire serving as a mosquito repellent—strategizing about how to save the little rookery from the marauders.

Years before Chapman had met Paul he had, in a sense, been a plume hunter himself (albeit for science). In 1898, for example, he took his new wife, Fanny, to honeymoon on Pelican Island. Other New York dandies

may have traveled to Niagara Falls or Bermuda on such an occasion, but Chapman (using Oak Lodge as headquarters) went with Fanny to the Indian River Lagoon to shoot and skin pelicans for the American Museum of Natural History. It turned out to be an inspired choice: the Chapmans marveled at the teeming seabird colony they encountered on that beloved lump of mud and mangrove. Late in life Chapman, by then a well-traveled naturalist, wrote that Pelican Island was “by far the most fascinating place it has ever been my fortune to see in the world of birds.”

34

Now, two years after his honeymoon, Chapman had returned to Pelican Island and discovered a 14 percent decline in pelicans. This troubled him greatly. Listening to Kroegel tell about his difficulties protecting the islet, Chapman grew indignant. He recognized that the “Feather Wars” were being fought, and that Kroegel was actually risking his life daily on behalf of the Florida Audubon Society. Then and there Chapman decided that enough was enough. He was now prepared to take the “Feathers War” directly to Roosevelt in the White House. Intuitively Chapman knew that his friend Roosevelt would immediately approve Kroegel’s gun, boat, and “badge,” sponsored by the Audubon Society. Roosevelt would want to shut the plumers’ operation down. Like the cowboys and ranchers Roosevelt admired in the Dakota Territory and the Rough Riders he led into battle—and like what Roosevelt fancied himself to be—Kroegel was a steely, live-off-the-land, never-say-die lover of wildlife. It was as if “the Virginian” had arrived in Vero Beach.

35

But Chapman was too wise to pester Roosevelt without first having a sensible game plan. He knew he needed to start with his fellow AOU members William Dutcher and Theodore Palmer. Dutcher was chairman of the AOU Bird Protection Committee and Palmer was assistant chief of the Division of Biological Survey. Both men were instrumental in advocating for bird protection throughout the United States. In fact, they were successful in helping persuade twenty-three states, including Florida in 1901, to pass the AOU model law protecting nongame birds. Florida’s new law enabled the AOU to begin employing wardens to enforce bird protection. Even before this new law was passed, Chapman understood that at Pelican Island more wildlife protection would be needed. He urged Dutcher and Palmer to investigate the possibility of purchasing Pelican Island. A year later, in April 1902, Dutcher hired Paul Kroegel as one of the new Audubon wardens, on the recommendation of Ma Latham.

36

And the AOU had a cadastral survey of Pelican Island drawn up by J. O. Fries in July 1902.

37

Here was the problem Chapman, Dutcher, and Palmer faced in trying to save Pelican Island: since the federal Lacey Act passed in 1900 and the AOU model law passed in Florida in 1901, the AOU had failed to purchase Pelican Island with Thayer Fund monies, as a result of a serious technicality. Because Pelican Island was designated “unsurveyed” U.S. government property, the General Land Office couldn’t legally authorize its acquisition to create a bird sanctuary. William Dutcher, however, cleverly directed Thayer Fund dollars to commission a survey of Pelican Island acceptable to the General Land Office. He may have been too clever by half. For just as Pelican Island was being officially surveyed—under Dutcher’s impetus—the AOU learned that it had opened up Pandora’s box: once the General Land Office approved the AOU survey, Pelican Island could then be made available to homesteaders. Free land for all who promised to grow crops or plant grapefruit trees—the worst possible scenario for saving the rookery. Even if the homesteading could somehow be averted, Dutcher feared that the New York millinary industry, with its deep pockets, would purposely outbid him just to spite the bird nuts and stick it to the Audubon Society.

38