The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (71 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

“Will you tell me how things are in the Yellowstone Park as regards game protection?,” Roosevelt wrote John Pitcher at Yellowstone on October 24, 1902. “I know the buffalo are almost gone, and I know how difficult it is to protect the beaver. How are the elk being protected? Is there much slaughter of them in the forest preserves outside of the Park, and is there much poaching of them in the Park itself? How are they holding their own? I should be very much obliged if you would give me any information about the game in the Park. What force of rangers have you?”

85

Undergirding Roosevelt’s promotion of the American wilderness from 1901 to 1909 was

Darwinism

—a word uttered reverently by the president. In

Nature’s Economy

(1977) the historian Donald Worster writes, convincingly, that ecology after Darwinism became a “dismal science” in America. Roosevelt, it seems, was an exception to this rule. When Darwin, for example, traveled to South America he encountered the “violence of nature,” including huge vultures, stalking jaguars, vampire bats, and poisonous snakes. It was a frightful land of volcanoes, earthquakes, and insect swarms. Everywhere Darwin looked in the jungles of South America there were “the universal signs of violence.” Ironically, Roosevelt was thrilled by nature’s violent side. He wasn’t like John Muir studying ferns or John Burroughs praising bluebirds. The blood-and-guts aspect of Darwin’s account appealed to Roosevelt. The president, in fact, felt part of

the bond of violence. Tumult, cataclysm, horror, and brutality in nature taught Roosevelt to immerse himself in defiance and struggle. On hunting excursions he was engaged in the dark pageant of earth, where death was always looming.

86

Forget Progressivism or Republicanism. From late 1901 onward President Roosevelt behaved like a Darwinian ideologue, disseminating the great naturalist’s ideas as if they were providential. It’s impossible to understand anything Roosevelt did or said without taking Darwin, Huxley, and Spencer into consideration. There was never a time when Roosevelt, the politician as inquiring scientist, didn’t want to know

everything

about the organic makeup of a forest reserve or a seabird or a moose antler. Besides being a utilitarian conservationist, Roosevelt felt he had a duty to inventory and catalog every type of beetle, lizard, mouse, pine cone, seedling, and wildflower in America. Like a modern-day Thomas Jefferson he wanted all of the American West cataloged as thoroughly as Darwin had cataloged the Galápagos. His handpicked Lewises and Clarks, in this regard, were employees of the Biological Survey, forestry experts like Pinchot, Audubonists of every stripe, and Bullock and Warford outdoors types. It was Roosevelt’s obsession with the

truths

of Darwinism and

pragmatism

of Pinchot that made his conservation policies so much more ambitious than those of Cleveland and McKinley. A good equation for understanding our twenty-sixth president is the following: Grinnell (hunting) + Darwin (evolution) + Pinchot (utilitarianism) + Burroughs (tender naturalist) = President Roosevelt.

87

T

HE

G

REAT

M

ISSISSIPPI

B

EAR

H

UNT AND

S

AVING THE

P

UERTO

R

ICAN

P

ARROT

I

D

eep in the southern Mississippi Delta near what was then the village of Smedes—on land situated between the Mississippi River to the west and the Little Sunflower River to the east—a historical marker in front of the Onward Store on Highway 61 now commemorates the most celebrated hunt in American history. In mid-November 1902 President Roosevelt, exhausted from mediating between mine owners and the striking members of the United Mine Workers (UMW), was in need of a short vacation. A few weeks earlier, public schools and government offices throughout the Northeast and Midwest had to be closed because there wasn’t enough coal to heat them, and the president had threatened to send federal troops to reopen the locked mines of Appalachia. Finally, a settlement was reached with the mine owners through arbitration, and a relieved Roosevelt was ready to go hunting.

1

This particular six-day Mississippi expedition, from November 13 to 18, resulted in a stuffed animal different from the kind produced by taxidermy: the most popular toy ever manufactured—the teddy bear (plus several apocryphal hunting yarns that have masqueraded as fact for more than a century).

2

After the coal crisis and the carriage crash, President Roosevelt eagerly accepted long-standing invitations from friends to come south for the bear hunting season. No state matters were going to detain him. An open air-vacation was to be the order of the day. The only real outdoors “breaks” he had in 1902 had been the Berkshires and a visit to the Bull Run Historic Battlefield to hunt for Virginia wild turkey on a chilly afternoon. He didn’t get one.

3

Naturally, politics also figured into Roosevelt’s decision to go south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Mississippi’s newspapers and politicians had been attacking the president with a vengeance over the Booker T. Washington affair. The white supremacist James K. Vardaman was a divisive and contentious newspaper publisher, who had lost a race for the governorship to Andrew Longino (a moderate on racial issues). Vardaman had daggers out for the president. In addition to being a bigot, Vardaman was a gaffe machine, unable to achieve even a sem

blance of political correctness.

4

When Democrats who favored Vardaman heard that Roosevelt was coming to Mississippi to hunt, they denounced the president as that “coon-flavored miscegenist in the White House” and a “nigger lover” hell-bent on destroying the last remnants of Confederate culture. Vardaman—like many white Southern Democrats—was still furious that this

Republican

president had invited Washington to dine at the White House the previous year. It was an unforgivable affront, he said, to Anglo-Saxon culture. Vardaman ran derogatory advertisements in newspapers in Jackson, Vicksburg, and Meridian in hopes of derailing the presidential trip. One read: “

WANTED

: 16

COONS TO SLEEP WITH ROOSEVELT WHEN HE COMES DOWN TO GO BEAR HUNTING WITH MISSISSIPPI GOVERNOR LONGY

.” Roosevelt’s claws of detractors were not limited to Southern Democrats. An anti-Roosevelt insurgency was brewing among the so-called “lily-white” Republicans, who wanted Mark Hanna to be the party’s presidential nominee in 1904.

5

Roosevelt wasn’t intimidated by the vile accumulation of race baiting, but he was acutely aware that this hunt was going to be carefully followed by the press. The Illinois Central Railroad gladly took care of Roosevelt’s transportation. He, in turn, cut quite a figure on the 1,000-mile journey from Washington to the Mississippi delta. The towns his train thrummed through—Tunica, Dundee, Lula, Clarksdale, Bobo, Alligator, Hushpuck-ena, Mound Bayou, Cleveland, Leland, Estill, Panter Burn, Nitta Yuma, Aguilla, and Rolling Fork—are today on or near the American “blues highway,” considered by many the birthplace of rock and roll. Throughout the delta that November the fields were covered with bright white bolls—a second cotton harvest. Clad in a fringed buckskin jacket he had acquired in the Dakota Territories, topped off with a brown slouch hat, the president looked like Seth Bullock of Deadwood, and the full cartridge belt around his waist added an air of a Rough Rider ready for action. The Mississippi River valley that loomed in front of him seemed stranger, even exotic. The president had already made a request of one of his hosts, Stuyvesant Fish, president of the Illinois Central Railroad: “My experience is that to try to combine a hunt and a picnic, generally means a poor picnic and always means a spoiled hunt,” Roosevelt wrote. “Every additional man on a hunt tends to hurt it. Of course I am only going because I want to

hunt

—and do see I get the first bear without fail.”

6

Reporters covering his train ride to Mississippi noted that Roosevelt was reading his friend the French ambassador Jean-Jules Jusserand’s

The Nomadic Life

, a history of the Crusades of the Middle Ages, and surmised that the text was meant to inject some intellectual adrenaline and roman

ticism into the preparations for the “Great Bear Hunt.” (Reporters could never account for Roosevelt’s eclectic reading tastes.) When the train entered the delta the view from the presidential compartment changed from rolling hills to unhindered flat plains. At each railroad platform were bales of cotton ready for shipping to the textile mills of New England and Europe. The always gregarious Roosevelt waved at the Mississippi field hands who lined the tracks for an unprecedented glimpse of a U.S. president. Blacks recognized that, whatever Roosevelt’s shortcomings, cruelty and injustice always moved him to action. Since the Booker T. Washington affair Roosevelt had become a hero to African-Americans and mulattos. Nonsegregationist newspapers in the Mississippi bottom reported the president’s trip positively. One headline read: “President Speeds to Bruin Land.” A few hamlets along the train route hung patriotic crepe paper streamers as a welcoming gesture.

By going to Mississippi, Roosevelt was hoping to accomplish a few things with regard to race. It was the twentieth century, and he felt that the South had to stop seeing the world as a bridge into the burning past. The first step for a new civil rights era, he believed, was to champion antilynching laws throughout the South and Middle West. Anyone lynching a black had to be vigorously prosecuted. Racist vigilantes, the president worried, had gotten out of control. On the economic front what troubled Roosevelt was that African-American cotton pickers were trapped in a dead end: their position as tenant farmers bordered on slavery. The economic situation was unaceptable below the Mason-Dixon Line thirty-seven years after the Civil War. How could he help lift the African-Americans of the Deep South out of their condition of peonage?

But grappling with the “Negro” condition was just part of his agenda in Mississippi. Roosevelt was extremely interested in seeing America’s agricultural sector increase under his leadership. Worried about declining farm ownership in the South, particularly in the delta, Roosevelt wanted to educate himself about how the price of the cotton crop could rise up from seven cents a pound to ten cents a pound. (By 1909 he had achieved this objective.) In fact, farm property values, as a result of Roosevelt’s agricultural policies,

doubled

throughout the United States between 1900 and 1910. Under the expert management of Secretary of Agriculture Wilson the Roosevelt administration also championed organized food inspection programs and improvements in rural roads. New levees were approved to help control annual overflows. “In many respects,” the historian Lewis L. Gould has pointed out, “his administration was an era of unmatched prosperity on the American farm.”

7

In addition to civil rights and his agriculture policy, there was a third factor that influenced Roosevelt to choose the Mississippi Delta for his first high-profile hunt as president: he tacitly acknowledged that he really wanted a black bear. Ever since the 1880s, when he had read two articles in

Scribner’s Magazine

by James Gordon—“Bear Hunting in the South” and “A Camp Hunt in Mississippi”—he had itched to explore the Coldwater, Tallahatchie, and Sunflower river floodplains. Such a hunt, of course, included braces of dogs, rough-haired little terriers that could dodge into the canebreak when the bear was enraged. They’d bark and snarl only a few inches from a bear’s muzzle. Other ritual activities were likewise followed. Besides Mississippi black bear, Roosevelt hoped to see tall cypresses rising out of the swamps and camp near cottonwoods reported to be ten feet in diameter. His team would cut through bayous with only moss, which grows on the north side of a tree, as a compass. And the southern planters he would be hunting with, he anticipated, were, as the sportsman Frank Forester once wrote, man for man the finest hunters in the western hemisphere.

8

Roosevelt was also hoping to mix with some crack-shot swampers and trampers.

Despite the light rain glazing the rails and the storm-threatening clouds darkening the horizon, when Roosevelt arrived in Smedes on the afternoon of Thursday, November 13, he was ready to hunt. The grayness was eerily appropriate. Buoyantly Roosevelt thanked the engineer, shook hands, signed autographs, and showed off his ivory-handled knife and custom-made Model 1894 Winchester rifle with its deluxe walnut stock. He felt good to be in bear country. For the most part his arrival time had been kept secret, so there weren’t many greeters in Smedes other than a large contingent of field workers who had taken the day off to see the president; these were the descendants of slaves.

9

Among those who had joined Roosevelt in Memphis were other members of his hunting party, including John M. Parker, president of the New Orleans Cotton Exchange who later became governor of Louisiana; John McIlhenny, who had been a lieutenant in the Rough Riders and had founded the Tabasco Company in New Iberia, Louisiana; and a local plantation owner, Hunger L. Foote, whose grandson Shelby would become one of America’s foremost Civil War historians. “My grandfather died before I was born,” Shelby Foote has recalled. “But I’ve got loads of newspaper clippings and photographs from the big hunt. There was no bigger event in our family history.”

10

The main tract of land where Roosevelt would hunt belonged to E. C. Magnum, a shareholder in the Illinois Central and, more important,

owner of the sprawling Smedes and Kelso plantations on which the hunt was conducted. Camp was set up on the bank of the Little Sunflower River about twelve miles east of Smedes, reachable after a bushwhacking ride on horseback through a dense tangle of prickly underbrush, stunted pines, sluggish bayous, and canebrake. There were also plenty of fine groves of oak and ash to navigate. Roosevelt had listened to the train chugging for days, and now the delta songbirds immediately provided nourishment to his ears. Supplies were delivered to the camp on mules and by wagon. A-frame sleeping tents had been assembled next to a huge cooking tent that had been erected earlier. That first night, the men swapped bear stories around a roaring bonfire on the bank of the Little Sunflower. Roosevelt’s tales of his cowboy adventures in the Wild West usually stole the show, but in this gathering the star raconteur was a fifty-six-year-old African-American, Holt Collier, chosen to lead this hunt because of his reputation as a bear tracker. There was a “glad to be alive” quality about Collier, to which Roosevelt naturally gravitated. “Though the hunt had been planned at high corporate and governmental levels for months,” the biographer Minor Ferris Buchanan recalled, “its success was wholly dependent upon the skill and performance of Holt Collier.”

11

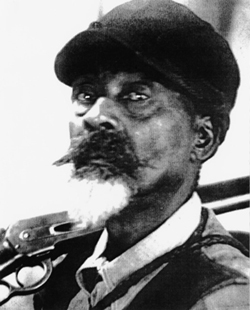

Collier had been born a slave in 1846 to the family of General Thomas Hinds, who won fame with Andrew Jackson at the battle of New Orleans. Collier never received a formal education and couldn’t even sign his own name. When he was a young boy, his job on the Plum Ridge Plantation had been to provide meat for the Hinds family and their field hands. Accordingly, Collier had killed his first bear with a twelve-gauge Scott shotgun in a wilderness swamp when he was only ten years old. Collier became a runaway slave at the age of fourteen but then, oddly (and intriguingly to Roosevelt), joined the Confederate army. (There was a prohibition against African-Americans serving in uniform in the Confederate army, but an exception was made for Collier.

12

) A brave, gallant soldier with a virile demeanor, he witnessed the death of General Albert Sidney Johnston at Shiloh. He signed up with Company I of the Ninth Texas Cavalry a few weeks later and saw combat in Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

Like the kind of folk figure Ramblin’ Jack Elliott or Woody Guthrie might sing about, Collier became a Texas cowboy during Reconstruction, driving cattle on the open prairie, spitting tobacco on the run. He had gone to Texas after being acquitted of the murder of a Union captain, James A. King of Newton, Iowa, in 1866. Upon hearing that Howell Hinds, his former master, had been murdered in Greenville, Collier came

back to Mississippi to avenge his death. Often involved in chasing fugitives, in gunfights, and in horse racing, and having spent decades as an expert guide, Collier had an unsurpassed reputation for being his own man, able to track bears or humans with unfailing instinct. As a marksman he had few peers in the delta. He lived closer to the ground and understood the local geography better than anybody else. Collier epitomized a forest trickster character that the South Carolina Gullahs called “Bur,” like “Bur Rabbit” or “Burr Bear.”