The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (131 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Next, inspired by Muir Woods, the Pinnacles, Cinder Cone, Lassen Peak, and other California sites that he had recently saved, Roosevelt began strategizing to make the six Farallon Islands off the coast of California a federal bird reservation, safe from human predation. The Farallons were a favorite roosting area for the common murre, black oystercatcher, and Leach’s storm petrel, but the Farallones Egg Company had plundered these islands by raiding nests and had taken an estimated 14 million eggs. Studying photographs of the islands, and enjoying the charming intimacy of seals and otters at play, Roosevelt decided to have the Biological Survey draw up documents for him to sign in early 1909. Even though San Franciscans were used to ransacking the islands, Roosevelt was going to cut them off as an act of charity and wisdom.

Roosevelt, however, let California’s preservationists down in one profound way. For all of his thoroughness, he didn’t back Muir’s wise opposition to flooding the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. Instead, he favored the short-term need for water rather than the long-term aesthetic value of Hetch Hetchy. In contrast to his self-congratulatory boasts during December, Roosevelt’s letter to the

Century’s

editor, the prominent conservationist Robert Underwood Johnson, exuded self-doubt. Was it smart to have approved a petition by San Francisco to convert Hetch Hetchy into

a reservoir, following the earthquake of 1906? Had he let the Sierra Club and John Muir down with regard to this conservation issue? “As for the Hetch Hetchy matter,” Roosevelt explained to Johnson, “it was just one of those cases where I was extremely doubtful; but finally I came to the conclusion that I ought to stand by Garfield and Pinchot’s judgment in the matter.”

96

Neither Johnson nor Muir held a noticeable grudge against Roosevelt for his disastrous decision concerning Hetch Hetchy (although they did hold a grudge against both Garfield and Pinchot).

And Roosevelt took his conservationism global that December. At the Joint Conservation Congress he rallied against the disease of global deforestation. Roosevelt invited Canada and Mexico to participate in the North America Conservation Congress on February 18, 1909, in Washington, D.C., for a simple reason: nature didn’t recognize artificial boundaries. If Mexico polluted the Rio Grande River, that would hurt the citizens of Texas. Similarly, if Canada overfished Lake Superior, the effect on Minnesota would be horrific. Roosevelt wanted Arbor Day to be international, because deforestation was a global curse. Also, every country needed tough antipollution laws to regulate the handling of sewage and industrial waste. Migratory birds needed protection like the Lacey Act everywhere from the Arctic to Antarctica, from Lassen Peak to the Himalayas. Roosevelt’s hope was that his conference of February between the United States, Canada, and Mexico might be the precursor to a global conference. “It is evident that natural resources are not limited by the boundary lines which separate nations,” Roosevelt said, “and that the need for conserving them upon this continent is as wide as the area upon which they exist.”

97

A final 1908 brouhaha occurred when Roosevelt declared Loch-Katrine in Wyoming a federal bird reservation, to protect a wide range of aquatic fowl as well as nesting bald eagles and peregrine falcons. Congressman Frank W. Mondell protested that Loch-Katrine Federal Bird Reservation was undemocratic. Wyoming had so sparse a population that it had only one congressman—Mondell, who with his long face, pointed eyebrows, and handlebar mustache, served in that capacity for twenty-six years. Mondell was the champion of Wyoming’s oil fields and coal mines. Imposing one of T.R.’s federal bird reservations on his state—not far from Teapot Dome—was, to him, nothing short of an act of war. On February 11, 1909, Mondell, a member of the committee on Public Lands (he would later be its chairman), wrote a scathing letter to Dr. Merriam, which was published in the

Congressional Record

. “I desire to dissent most emphati

cally,” he wrote about Loch-Katrine, “and to register my protest against the order in question.”

98

By January 1909 Roosevelt felt a great thirst rising in him. The idea of being a lame-duck president, sitting in a chair and letting his paunch expand, when he had nine weeks to achieve

American things

, was ludicrous. Roosevelt believed that instead of pardoning people, outgoing presidents should compile a list of social ills in need of solving. There would be no idling in the White House corridors. When the editor of

Saturday Review

asked Roosevelt how to sum up his executive modus operandi, the president’s answer was revealing. “My business was to take hold of the Conservative [Republican] Party and turn it into what it had been under Lincoln,” Roosevelt wrote, “that is, a party of progressive conservatism, or conservative radicalism; for of course wise radicalism and wise conservatism go hand in hand.”

99

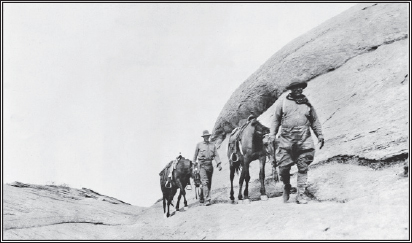

As ex-president, Roosevelt hiked the canyonlands of the American Southwest, many of which he had saved by designating them as national monuments.

T.R. hiking the canyonlands of Utah. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

D

ANGEROUS

A

NTAGONIST

: T

HE

L

AST

B

OLD

S

TEPS OF

1909

I

T

o some, President Roosevelt looked tired during his last days in the White House; his exhausted face seemed to consist of only the two eyes, with dark shadows like a raccoon’s mask. Unapologetic for riding roughshod over Congress, Roosevelt seemed to enjoy being an all-around nuisance on the Hill. In fact, he had developed a sense of mischievousness in early January 1909. While reporters were gossiping about William Howard Taft’s cabinet appointments, the fifty-one-year-old Roosevelt started to put into motion his last bold conservationist acts as president. Owing to his intense connection with the outliers of America, he seemed to feel immune from the disapproval of Washington’s opinion-makers. The

people

were with him. Conjuring up the ghost of Grover Cleveland—who had set aside 7 million acres of forest reserves as a parting gesture in 1897—Roosevelt was ready to trump his predecessor. “Ha ha!” Roosevelt had written to Taft on New Year’s eve: “While you are making up your Cabinet, I, in a lighthearted way, have spent the morning testing the rifles for my African trip.”

1

Playing kingmaker, Roosevelt had selected the fifty-one-year-old Taft over the more senior Charles Evan Hughes, Elihu Root, and Joe Cannon to be his successor as the Republican candidate for president. The voters agreed that Taft was the logical choice; his experience as the chief civil administrator of the Philippines and as secretary of war qualified him to be the commander in chief. Keep in mind, though, that whoever was chosen by Roosevelt in 1908 would have been likely to defeat William Jennings Bryan, so Taft clearly owed his good fortune to Roosevelt. One evening during his second term, following his surprise announcement that he wouldn’t be a presidential candidate in 1908, Roosevelt invited Taft (and Taft’s wife, Nellie) to a private dinner at the White House. After dessert Roosevelt and the Tafts repaired to the library for serious conversation. Leaning back in his leather armchair Roosevelt began to pretend that he had prophetic powers. Squeezing his eyes shut, gazing upward, he jok

ingly chanted: “I am the seventh son of a seventh daughter. I have clairvoyant power. I see a man before me weighing three hundred and fifty pounds. There is something hanging over his head. I cannot make out what it is; it is hanging by a slender thread. At one time it looks like the presidency—then again it looks like the chief justiceship.”

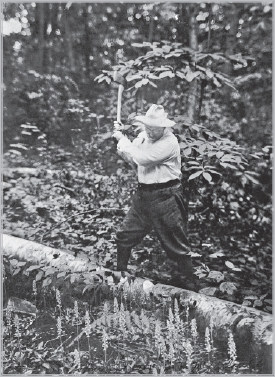

Roosevelt enjoyed chopping his own firewood and clearing his own paths in the wild.

T.R. chopping firewood. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

“Make it the presidency!” Nellie burst out excitedly.

“Make it the chief justiceship!” Taft quickly interjected, not wanting history to record that he had

asked

to be president.

2

Of course, Taft welcomed Roosevelt’s nod. But already in January 1909, Roosevelt was becoming lukewarm about his handpicked successor. Taft wasn’t offering administrative jobs to young, progressive Republicans as T.R. had hoped. Many holdovers from Roosevelt’s administration, in fact, were being dismissed. And Taft didn’t even seem to know what the Biological Survey and the Forest Service were. On a number of occasions Taft treated Pinchot like someone to be brushed aside. Roosevelt, still only middle-aged, perhaps realized that he was going to miss wielding power. “I should like to have stayed on in the Presidency, and I make

no pretense that I am glad to be relieved of my official duties,” he wrote to Cecil Spring-Rice. “The only reason I did not stay on was because I felt that I ought not to.”

3

Adding to Roosevelt’s discomfort with president-elect Taft was that Taft dismissed James R. Garfield as secretary of the interior in January 1909. Roosevelt kept his composure. But in his eyes Taft now had two strikes against him. “No one knows exactly why Taft chose to drop Garfield,” historian M. Nelson McGreary writes in

Gifford Pinchot

, “but many of the various explanations boil down to a general feeling on the part of Taft that Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior was a bit overzealous in his support of conservation and was inclined to stretch the exact letter of the law on occasion in order to protect what Garfield felt was the public interest.”

4

Moreover, Roosevelt worried that Taft would be too frightened to initiate antitrust suits.

Some of Roosevelt’s friends, sensing an impending rift between the outgoing and incoming presidents, scrambled to find a meaningful position for Roosevelt; the possibilities included becoming a U.S. congressman and becoming president of Harvard University. Civic organizations also sought ways to memorialize him in plaques, bas-reliefs, and newsletters. Only half-jokingly, Senator Philander Knox declared that Roosevelt “should be made a Bishop.” And magazines offered Roosevelt substantial sums of money to write for them. He declined the offers from major magazines, on the principle of not selling out the presidency, but he did sign on with

Outlook

, a minor but important periodical for which he would write approximately a dozen long articles a year (like those that now appear on op-ed pages), for $12,000.

5

Roosevelt’s big money came from an arrangement with

Scribner’s Magazine

to write a series of articles that would eventually become the book

African Game Trails

. Determined that his specimen collecting not be written up as a “game butchering trip,” and wanting to frame his adventure as Wildlife Conservation, Roosevelt had Andrew Carnegie donate $75,000 for the presumably scientific expedition. With reporters, in fact, Roosevelt incessantly stressed that he was working for the Smithsonian Institution; only a few duplicate trophies would be kept for his wall at Sagamore Hill. And with due diligence Roosevelt started reading everything on such African explorer-hunters as Gordon Cummins and Cornwallis Harris.

6

Instead of mocking the thirty-four-year-old Winston Churchill as he had done in the fall, Roosevelt now carefully read Churchill’s

My African Journey

(1908) and was impressed that the author had bagged a white rhinoceros.

7

Roosevelt also wanted to hunt a rhinoceros, because

America couldn’t let the indefatigable Britons have the edge in natural history anymore.

To get into physical shape for Africa, Roosevelt would ride horseback every day to the point of exhaustion. “The last fifteen miles were done in pitch darkness and with a blizzard of sleet blowing in our faces,” the president wrote his son Kermit. “But we got thru safely, altho we are a little stiff and tired nobody is laid up.”

8

And he raced his favorite horse over fifty miles a day that January, as if preparing to charge up San Juan Hill. He would need to make the American scientific societies and explorers’ clubs proud when he was abroad. Friends from the Cosmos Club were concerned that by trying to get into trim, Roosevelt would suffer a heart attack or stroke. Jokes circulated on Capitol Hill that “crazy Teddy” was going to die from the strenuous life, now that he was a fat ex-president loaded down with guns. Some people scoffed that with his White House tenure winding down, he was little more than a rusted bolt, hard to shake loose.

With no congressional legislation pending, Roosevelt, as interregnum presidents are likely to be, was written off as a lame duck that winter. Big business, in particular, anticipating revenge, couldn’t wait for Roosevelt’s passport to be stamped in some godforsaken African port. “Congress of course feels that I will never again have to be reckoned with,” Roosevelt noted, “and that it’s safe to be ugly with me.”

9

In focusing so much on his forthcoming African safari, congressional Democrats, in particular, hoped Roosevelt’s radical conservationist crusade would peter out. However, regardless of what dark thoughts Taft harbored about Gifford Pinchot personally, he nevertheless had to embrace Roosevelt’s conservation on the campaign trail in 1908. To challenge Roosevelt on forestry would have been a death knell to Taft’s candidacy. “If I am elected President,” Taft said in Sandusky, Ohio, “I propose to devote all the ability that is in me to the constructive work of suggesting to Congress the means by which Roosevelt policies shall be clinched.”

10

After enduring T.R. in the White House for seven and a half years, the legislators should have known that he would be setting traps in early 1909. “I have a very strong feeling that it is a President’s duty to get on with Congress if he possibly can, and that it is a reflection upon him if he and Congress come to a complete break,” the president wrote to Ted, Jr. “This session, however, they felt it was safe utterly to disregard me because I was going out and my successor had been elected; and I made up my mind that it was just a case, where the exception to the rule applied and that if I did not fight, and fight hard, I should be put in a

contemptible position. While inasmuch as I was going out on the 4th of March I did not have to pay heed to our ability to cooperate in the fortune. The result has, I think, justified my wisdom. I have come out ahead so far, and I have been full President right up to the end—which hardly any other President ever has been.”

11

So, while wags laughed about Roosevelt’s African trip, the president acted. Congressmen had been asleep in 1903 when Roosevelt had created his first federal bird reservation at Pelican Island, Florida. Now, with Dr. Merriam of the Biological Survey still his steadfast ally, Roosevelt began rapidly declaring federal bird reservations during the last six weeks of his administration. He began with the Hawaiian territory: on February 3, he signed Executive Order 1019, declaring an entire archipelago of the Hawaiian Islands a federal bird reservation.

In 1903 Roosevelt had sent U.S. Marines to safeguard the seabirds of the Midway atoll, securing it as an American possession. Now he was saving the relatively nearby islands around Nihoa Island to Kure atoll from plumers and Japanese poachers. If you looked in an atlas for these flyspeck islands—west of the world’s largest lighthouse, on Kauai—the phrase “far-flung” might come to mind. But although human civilization might not have been thriving in this island group, the birds were there in magnificent numbers.

12

“To many these remote, shimmering, uninhabited islands are devoid of interest; to the naturalist, however, every square foot of the surface, and all the life that inhabits them, has an interesting story to tell,” a professor of zoology, William Alanson Bryan of the College of Hawaii, remarked in 1915. “The geologist finds in them subjects of the greatest interest and importance.”

13

When Mark Twain wrote

Roughing It

in 1871, he presented Hawaii to the American reading public as an exotic place. Geologically, Twain had focused on a volcano (a “muffled torch”), claiming that in Hawaii lava flowed like a “pillar of fire.”

14

To Roosevelt this was a sure sign of a lazy journalist resorting to clichés: Twain made no mention of humpback whales, spinner dolphins, koa trees, or yellow hibiscuses. And then there was Jack London, who went to Hawaii in the yacht

Snark

but knew nothing of sea urchins or the numerous types of dolphins and sadly believed that he grew funnier as the bottle emptied. Robert Louis Stevenson had spent time in Hawaii during 1889, but he had chosen to focus on leprosy.

From Roosevelt’s perspective any indigenous Hawaiian chant—for example, the Kauai prayer “Hanohano Pihanakalani”—had more connection to the natural environment of Hawaii than a page by Twain,

London, or Stevenson. Natives sang of the exquisite uplands, mountain shells, mokihana trees, and rare terns.

15

But the literary “nature fakers” gave false pre-Darwinian descriptions of tropical vegetation that didn’t even exist on the islands. Didn’t Twain have eyes for the Hawaiian stilt, with its long pink legs? Couldn’t London comment on the green sea turtles? Wasn’t Stevenson competent enough to write about one of the forty species of sharks in the waters of Hawaii? The point was obvious: these literary men couldn’t have distinguished a hammerhead from a whitetip reef shark. Why didn’t important American writers study Hawaiian coral reefs, home to more than 7,000 marine species? Roosevelt believed that an accurate inventory of Hawaii’s fauna and flora in the form of a popular book was sadly needed.

Roosevelt’s intense interest in Hawaii went back to his expansionist fever of the 1890s. In 1893, in fact, Roosevelt had cheered as American colonists, mainly sugarcane growers, toppled a kingdom and replaced it with the republic of Hawaii. As assistant secretary of the navy he had lobbied Congress fervently to annex the island for strategic reasons. That effort had become a standard part of his public business in 1898. On April 30, 1900, Hawaii finally became an official U.S. territory; and a jubilant Roosevelt couldn’t wait to loll on the sand beaches, watching the surf roll in, perhaps using the Hawaiian Islands as stepping-stones on his way to Japan or Australia.

Doing his homework, Roosevelt now homed in on saving the far northwestern Hawaiian Island chain in the mid-Pacific, including Nihoa, Necker, French Frigate Shoals, Gardner Pinnacles, Maro Reef, Laysan Island, Lisianski Island, and Pearl and Hermes atolls, before leaving the White House. There were twenty-one islands plus smaller ones contiguous to the big nine. Executive Order 1019 designated the entire chain as a single federal bird reservation.

*

While Pearl Harbor was the supreme port, the Hawaiian Islands Federal Bird Reservation had such stunningly diverse wildlife—including blue gray noddies, wolf spiders, and monk seals—that as an ecosystem it defied classification.

16

Geologists supposed that these islands were the summits of submerged mountains, but that was only a guess. An intruder’s foot would step on a bird burrow with practically every stride.

17

Everywhere there are birds,” ornithologist William Palmer wrote on the islands of Executive Order 1019, “thousands upon thousands of albatross, white and brown, in great, distinct colo

nies; great rookeries of terns and petrels and frigate birds; countless rail run everywhere in the long grass; bright red tropical honey birds, bright yellow finches flutter in the shrubs; curlews scream; ducks quack; crake chirp all the day.”

18