The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (111 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Kermit, now sixteen years old, was full of gratitude that his father sent him such marvelous notes from Panama, from Puerto Rico, and at sea.

But he seems to have thought somewhat differently in early December. News came that his father—President Theodore Roosevelt—had won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating a settlement in the Russo-Japanese War. Not surprisingly, as the first American ever to win this honor, Roosevelt was pleased. But he was also concerned about the $40,000 check that accompanied the prize. After all, he had spent much of his public career huffing and puffing against bribery and corruption. He had made peace between Japan and Russia because it was his job as president. Ethically, the $40,000 didn’t belong to him.

To Kermit, his father was just being unduly foolish. The money could properly be used to build a new wing on Sagamore Hill, to travel around the world, or to earn interest in an inheritance fund for him and his brothers and sisters. Shouldn’t the Roosevelt family enjoy this gift? His father, that December, deplored such self-indulgent notions. “Now,” the president wrote to Kermit, “I hate to do anything foolish or quixotic and above all I hate to do anything that means the refusal of money which would ultimately come to you children. But mother and I talked it over and came to the conclusion that while I was President at any rate, and perhaps anyhow, I could not accept money given to me for making peace between two nations, especially when I was able to make peace simply because I was President. To receive money for making peace would in any event be a little too much like being given money for rescuing a man from drowning, or for performing a daring feat in war.”

81

A prisoner of old ethics, Roosevelt received the check that December. He used it to create a committee in Washington, D.C., for industrial peace.

On December 8, Roosevelt had signed quietistic declarations establishing Montezuma Castle (Arizona), El Morro (New Mexico), and the Petrified Forest (Arizona) as national monuments under the Antiquities Act of 1906. The three monuments were a tribute to Lacey’s trademark persistence on their behalf. If Lacey hadn’t been a teetotaler, he might have uncorked a bottle of Dom Perignon when told of this order. In Arizona, Wetherill excitedly anticipated more tourists than he could shepherd to see the ancient sites. Roosevelt had created all three monuments as a federal measure to deter artifact thieves and promote scientific study. He understood that these southwestern ruins and petroglyphs were windows to understanding the prehistoric cliff dwellings, pueblo ruins, and early missions discovered by army officers, ethnologists, cowboys, and explorers on the vast public lands in the territories. The story of ancient peoples could be analyzed better in these three monuments than anywhere else in North America; the ruins were that intact. Thanks to the Antiqui

ties Act, nobody was allowed to excavate or appropriate anything from Montezuma Castle, El Morro, or the Petrified Forest without permission from the relevant department (War, Agriculture, or Interior). As Charles F. Lummis wrote in

St. Nicholas

, an illustrated magazine for young adults, these monuments were in a part of the United States which “Americans know [as] little as they do Central Africa.”

82

The historian Josh Protas has noted, in

A Past Preserved in Stone

, that the “diversity” of Southwestern monuments “set a precedent for the types of monuments that would later be established.”

83

Take, for example, El Morro, on the Colorado Plateau. More than 2,000 inscriptions and petroglyphs were carved into the soft sandstone by explorers, pioneers, and native tribes. Much of western history may have been lost when pioneers headed down the Santa Fe Trail, but at El Morro some clues were left behind. Located five miles from Trinidad, New Mexico, this ancestral Pueblo ruin is at an elevation of 7,219 feet. Probably fewer than 1,000 easterners had seen it by 1906. Apparently, the ancients had used El Morro as a reliable water hole and campsite. At the time T.R. declared El Morro a national monument, the walls carved with signatures looked like a gigantic hotel register. Once again, thanks to Roosevelt, El Morro was now a treasured place, saved for future generations to study and enjoy.

Montezuma Castle National Monument of Arizona featured amazing cliff dwellings that had been molded and lived in by the pre-Columbian Sinagua around AD 1400. The Sinagua had once prospered, developing a sophisticated culture, but then inexplicably vanished. To many people, the Arizona cliff dwellings they left behind were among the wonders of the world. Nobody really knew what to make of them. The Verde Valley area overlooking Beaver Creek had been named by Europeans for the Aztec emperor of Mexico—Montezuma II—in the mistaken belief that he had once lived there, and the misnomer stuck. An early advocate of protecting Montezuma Castle was T.R.’s old Rough Rider friend William “Buckey” O’Neill, who besides being a mayor of Prescott, Arizona, was the editor of

Hoof and Horn

. To O’Neill, the Montezuma Castle cliff dwellings, much like Mesa Verde, raised more questions than they answered. Why did the Sinagua leave? Archaeologists offered conflicting answers to such questions, though warfare and drought seemed the most logical reasons. Now, professional anthropologists and archaeologists could study Montezuma Castle’s axes, tools, shells, paints, bone implements, and other artifacts with federal protection.

Because the Roosevelt administration didn’t have cash to spare, the

Arizona Antiquities Association started repairing Montezuma Castle and put up a protective metal roof. Tourists at Phoenix and Prescott now became enthusiastic about day outings to Montezuma Castle. As a promotional gimmick, it was said that Kit Carson had favored the ruins; he

had

once camped in the area. There were murmurs in the Tucson newspaper that Montezuma Castle should become a national park. All of Arizona was proud of Montezuma Castle. “We were (and perhaps still are) attracted to the ruins, no matter what their size or age,” John B. Jackson wrote in

A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time

. “Their shabbiness served to bring something like a time scale to a landscape, which for all its solemn beauty failed to register the passage of time.”

84

But it was Petrified Forest National Monument that created a flash of satori in preservationist circles. If a swath of Arizona’s Painted Desert strewn with petrified coniferous trees could be saved, so could Florida’s swamps, Louisiana’s brackish marshes, and Alaska’s tundra. Lacey, who had crisscrossed the country in his effort to save the Petrified Forest—which he considered one of America’s five most striking wonders, along with Yellowstone, Crater Lake, Yosemite, and Wind Cave—celebrated at his home in Oskaloosa. Nobody in public life could speak about the Petrified Forest quite like Lacey, even though he came from Iowa. He believed that many of the petrified logs had grown exactly where they now lay. Every log impregnated with silica, stained by iron oxide and other minerals, was a rainbow of colors. “Ages ago, so long that it makes one dizzy to think of it, these trees were alive and growing in the Southwest,” Lacey said. “They were coniferous, as shown by microscopic examination of their texture. The species is extinct, and the nearest resembling species now found exists in Asia Minor. The geological history of this forest is easy to read. The trees fell and floated around in some old arm of the sea until the roots and limbs were worn and rounded just as we see like examples on the sandbars of the Mississippi. The trees became heavy and waterlogged and settled to the sea bottom.”

85

Thanks to the guardian spirit of Theodore Roosevelt and John F. Lacey, this ancient sea bottom filled with petrified logs in eastern Arizona was an American treasure for future generations to study and enjoy. And Wetherill was ready to enforce federal protection even in treeless vales where the grass blades had perished due to the pounding sun.

T

HE

P

REHISTORIC

S

ITES OF

1907

I

E

ven with the administration’s designation of Petrified Forest, Montezuma Castle, and El Morro as national monuments in December 1906, President Roosevelt wasn’t content. Because John F. Lacey was no longer in Congress, Roosevelt had less clout with the House Committee on Public Land. Furthermore, the relationship between Interior and the USDA’s Forest Service was not congenial. By January 1907, Roosevelt had grown increasingly suspicious that his secretary of the interior, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, was too soft on the extraction industries in the West. Hitchcock was like a well-trained bullfighter who made his best passes when there was no bull present (or, as Roosevelt saw it, receded into the shadows when a real goring was possible). Easing Hitchcock, a McKinley man at heart, out of the post, became a priority for Roosevelt in early 1907. Finesse was needed because Roosevelt didn’t want to cut the life-line while Hitchcock was still making policy. Another consideration was allowing Hitchcock to reenter the private sector with honor, and this too became a priority for the administration over the holiday season. The situation was especially sensitive because Hitchcock, who was then sixty-one, was feeble (he died in 1909).

As of January 15—the day of the Senate’s official confirmation—Roosevelt’s new secretary of the interior was James R. Garfield of Ohio. Everybody in Washington knew Garfield as one of Roosevelt’s staunchest foot soldiers. As the saying went, he was an old head on young shoulders. Yet he was always something of a messenger boy. And it didn’t hurt that Garfield’s wife, the former Helen Newell of Cleveland, Ohio, was a prominent Washington hostess (part of the first lady’s elegant clique). “Garfield is earnest,” the

Saturday Evening Post

wrote. “The President likes earnest persons. Garfield is ambitious. The President likes ambitious persons. Garfield is conscientious, and the President lays much stock by that. In short, Garfield is a clean young man, with a mind that grapples with great problems, no matter what the windup of the encounter may be.”

1

Roosevelt wanted somebody to go after the perpetrators of land fraud in the West, a fellow Republican progressive unafraid of controversy. Garfield was his beau ideal. The handsome forty-two-year-old Garfield

had served in the Ohio state senate from 1896 to 1899. He was rara avis because of his old-fashioned sense of bedrock loyalty, always a character trait in short supply. As a silver-star bonus, Garfield was the son of James A. Garfield, the twentieth president of the United States, and had been weaned on national politics. For all their differences, Roosevelt knew that the elder Garfield had been a man of biting intelligence. Young James was a student at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, when his father was assassinated and he had witnessed the ghastly shooting, which happened at the Baltimore and Potomac railroad station in Washington, D.C., during his summer break. Somehow he had absorbed the assassination faster than much of the country did, and he refused to let the tragedy derail his ambition. In 1881 he enrolled at Williams College, where he earned straight A grades. Following college Garfield earned a J.D. degree from Columbia University, developing a formidable, Rooseveltian prosecutorial bent. Garfield wasn’t afraid to rouse lions from their lairs in the name of good government.

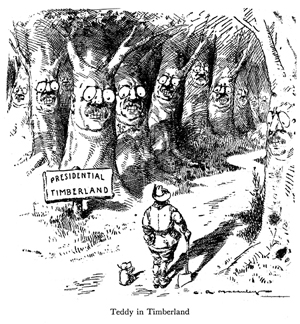

“Teddy in Timberland” was a popular cartoon that ran in syndication.

“Presidential Timberland.”

(Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Association)

From 1902 to 1903 Garfield was Roosevelt’s eyes and ears at the U.S.

Civil Service Commission. His professional attitude was characterized by following orders and saying “Yes sir.” Bosses, including Roosevelt, naturally admired that sort of man; and in addition, Garfield was competent. He was promoted to commissioner of corporations at the Department of Commerce and Labor. With the zeal of Lincoln Steffens he lashed out against the corrupt industries of the era: oil, steel, railroads, and meatpacking. Perhaps Garfield was only following orders, but he seemed to relish what we might now describe as being Roosevelt’s pit bull. At the very least Garfield understood that the fight for national forestry would be prolonged and intense. Now, in early 1907, Roosevelt wanted to sic Garfield on the timber thieves and land hustlers. As Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Garfield saw it, forestry was a science based on truth—not a political game in which you tried to score points in order to be reelected. “He has a man’s job before him now,” the

Washington Post

wrote of Garfield that spring. “The Department of the Interior controls the public domain, the forests, the Indians, the patents, the pensions, the Bureau of Education, the Geological Survey, and the Reclamation Service. All the land grafters, all the Indian grafters, all the sharks who are trying to get the timber and the oil and the coal for nothing must come to him and pass under his eye.”

2

The unflappable Garfield immediately was in full stride, walking directly into the line of fire. When the Republican Party lost House seats, pro-business newspapers started attacking Roosevelt for his antagonistic attitude toward Wall Street, big timber, and Standard Oil. For example, Edward Payson Ripley, president of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe, said that Roosevelt didn’t have the public interest at heart in creating forest reserves and national monuments. To Ripley, Roosevelt was simply obsessed with the wilderness. The railroad tycoon E. H. Harriman—who had sponsored the Alaska expedition that included Dr. C. Hart Merriam and John Burroughs, had a similar opinion—deeming Roosevelt a self-promoter and a traitor to his class. Roosevelt, for his part, started instructing Garfield to defend Native Americans from corporate land grabs in Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Montana. George Bird Grinnell was starting to write ethnographic books on Indians—he was doing research for a study that would be published as

By Cheyenne Campfires

. His work was starting to rub off on Roosevelt.

3

In a court order, Roosevelt defined Garfield’s job as protecting the “rapidly disappearing timber” for future generations to enjoy. America’s forests, Roosevelt believed, belonged to the homeland, but the homeland was under siege by underregulated industrialization (in other words, big business run amok). “Oil and gas,”

Roosevelt wrote to Garfield on February 1, 1907—“I most emphatically believe that we should not permit the lands containing oil and gas to be alienated under conditions which would in effect mean the building up of a great monopoly in oil.”

4

With the success of the Antiquities Act in 1906, Roosevelt had become even more dangerous to western developers, railroad companies, and oil companies. He usually donned a Stetson hat and often wore a bandanna around his neck, and his public rhetoric was full of western toponyms, cowboyisms, and Indian words not often heard in the East. From the White House, he was playing a Rocky Mountain man to help sell his radical conservationism. The oilmen, land developers, and trust titans wanted to see Roosevelt relegated to the sidelines of public life, like John F. Lacey. Instead, they had to confront not only Roosevelt but also Garfield. The timber industry believed that T.R.’s excessive conservationist initiatives were symptoms of his having gone berserk. But such hostility only encouraged Roosevelt to thrust himself forward as the true guardian of America’s natural resources. Figuratively, conservationism was simply the wise, righteous preservation of the American way, the prerequisite to Roosevelt’s building a republic like none other. “The grazing states, especially Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, protested vigorously against the new policies,” the historian Roy M. Robbins noted in

Our Landed Heritage

. “The stockmen of these states were compelled to use the meadows in the reserves inasmuch as the lower plains gave out during hot weather. The sheepmen were especially anxious, for fear that government regulation would curtail their operations in favor of cattle interests. Both those groups looked with suspicion upon policy which seemed to favor the homesteader.”

5

Working closely with Pinchot, Roosevelt began scheming for innovative ways to create dozens of new national forests before Congress reconvened on March 3. These forests would humanize the soul—if not, the Dark Ages would come to America (or so Roosevelt supposed). On February 23, 1907, in fact, a disgusted senator—Charles Fulton of Oregon, a fellow Republican—introduced the following amendment to an agricultural appropriations bill: “hereafter no forest reserve shall be created, nor shall any addition be made to one heretofore created, within the limits of the State of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Colorado, or Wyoming except by act of Congress.”

6

Fulton believed the whole Antiquities Act was nonsense and had to be curtailed. He was sick and tired of arrogant executive orders that gave petrified logs and spotted owls priority over business profits. Also,

Fulton said, the lowly settler and the poor farmer were being denied the same rich timberlands by the Roosevelt administration. This was a grim consequence of the government’s irresponsible hoarding of resources.

Roosevelt’s answer to Fulton was dramatic. On March 2, 1907—four days before the amendment was slated for a vote—Roosevelt released a document to Congress as a presidential fait accompli. Thirty-two new forest reserves had been created, seemingly overnight. Behind each forest listed were snatches of complicated conversations his representatives had conducted with state legislators and land managers about soil erosion, runoff, and deforestation. Numerous papers, passes, exemptions, validations, dues, expansions, and limitations had been issued. Roosevelt’s refusal to let Congress inhibit him caused a firestorm against him on Capitol Hill. By contrast, in sleepy Oskaloosa, where he had resumed his law practice on Main Street, Lacey deemed it a great day in the annals of forestry. Roosevelt had delivered a punishing blow to the advocates of states’ rights. He had caught Congress flat-footed. And the lumberman’s axes had been stilled in certain heavily forested regions, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.

The conservationist pronouncement of March 2 was a fine example of Roosevelt’s unappeasable conservationism. Roosevelt issued a long “Memorandum” listing forest reserves either created or enlarged:

Toiyabe Forest Reserve, Nevada

Wenaha Forest Reserve, Oregon and Washington

Las Animas Forest Reserve, Colorado and New Mexico

Colville Forest Reserve, Washington

Siskiyou Forest Reserve, Oregon

Bear Lodge Forest Reserve, Wyoming

Holy Cross Forest Reserve, Colorado

Uncompahgre Forest Reserve, Colorado

Park Range Forest Reserve, Colorado

Imnaha Forest Reserve, Oregon

Big Belt Forest Reserve, Montana

Big Hole Forest Reserve, Idaho and Montana

Otter Forest Reserve, Montana

Lewis and Clark Forest Reserve, Montana

Montezuma Forest Reserve, Colorado

Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington

Little Rockies Forest Reserve, Montana

San Juan Forest Reserve, Colorado

Medicine Bow Forest Reserve, Wyoming, Colorado

Yellowstone Forest Reserve, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming

Port Neuf Forest Reserve, Idaho

Palouse Forest Reserve, Idaho

Weiser Forest Reserve, Idaho

Priest River Forest Reserve, Idaho and Washington

Cabinet Forest Reserve, Montana and Idaho

Rainier Forest Reserve, Washington

Washington Forest Reserve, Washington

Ashland Forest Reserve, Oregon

Coquille Forest Reserve, Oregon

Cascade Forest Reserve, Oregon

Umpqua Forest Reserve, Oregon

Blue Mountain Forest Reserve, Oregon

7

When Fulton heard that huge tracts of Oregon forestlands had been pickpocketed by the federal government before the agriculture bill could be voted on, he was furious. No serious American, he believed, could have designated so many western forest reserves in such a cavalier fashion. It was a gray, grim day, Fulton lamented, for Willamette valley’s businessmen. According to Fulton’s tirade, Roosevelt and Pinchot’s team had sneakily withdrawn 16 million acres, ostensibly to prevent overlogging. And eight of the forest reserves were in Oregon: Wenaha, Siskiyou, Imnaha, Ashland, Coquille, Cascade, Umpqua, and Blue Mountain.

8

The whole damn state, Fulton fumed, was becoming a park. The lumber warehouses and industrial storage sheds in his state would be empty if this type of land grab was tolerated. A torrent of accusations followed: Why didn’t Roosevelt burn the Constitution while he was at it? Why didn’t he just declare Oregon a colony and get it over with? Why didn’t he ban sawmills from operating in the West?

Not for a second did Fulton believe that the autocratic Roosevelt was preserving millions of acres for homesteaders or for posterity. The new forest reserves were, to his mind, something the aristocrats of the Boone and Crockett Club and the Audubon Society wanted to have as trophies, at the expense of hardworking, taxpaying citizens. And in general, western interests claimed that this was foul play. Roosevelt, they believed, had acted dishonorably by setting aside the 16 million acres of forest reserves without proper congressional consultation.

9