The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 (48 page)

Read The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 Online

Authors: Mark Thompson

Tags: #Europe, #World War I, #Italy, #20th century history: c 1900 to c 2000, #Military History, #European history, #War & defence operations, #General, #Military - World War I, #1914-1918, #Italy - History, #Europe - Italy, #First World War, #History - Military, #Military, #War, #History

The men are not fighting. That’s the situation, and plainly a disaster is imminent … Do not worry about me, my conscience is wholly clean … I am very calm indeed and too proud to be affected by anything that anybody can say. I shall go and live somewhere far away and not ask anything of anyone.

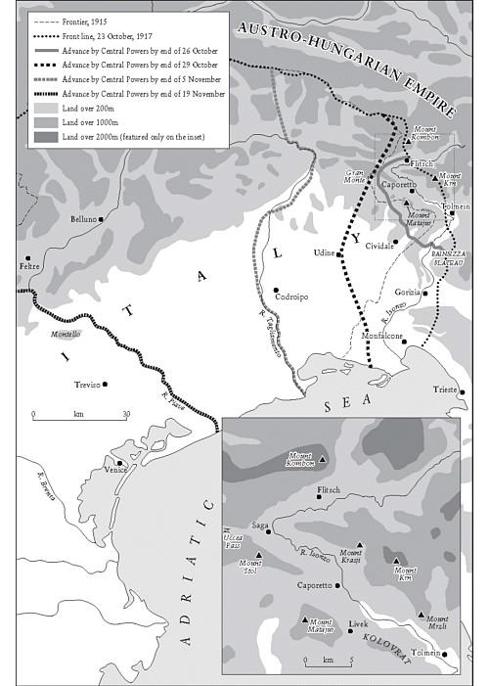

By the end of the second day, the Central Powers controlled the Isonzo north of Tolmein. Mount Stol and the Kolovrat–Matajur ridge were on the point of falling. In the south, Badoglio had apparently abandoned his divisions after, or even before, they disintegrated, putting the middle Isonzo in jeopardy. The Duke of Aosta continued to prepare a retreat, moving his heavy batteries westward.

Still Cadorna procrastinated. He painted an encouraging view in the daily bulletin, claiming falsely that Saga had not fallen and that the enemy had made headway further south because Italian interdiction fire had been negated by fog. Then he telegraphed the government: ‘Losses are very heavy. Around ten regiments have surrendered without fighting. A disaster is looming, I shall resist to the last.’ Before this grim message reached Rome, the government lost a vote of confidence by 314 to 96 votes. The Socialists and anti-war Liberals had brought Boselli down. Cadorna predicted correctly that the new prime minister would be his main enemy in the cabinet, Vittorio Orlando.

Meanwhile soldiers streamed westwards, throwing away their rifles and chanting ‘The war’s over! We’re going home! Up with the Pope! Up with Russia!’ Around midnight Cadorna, Porro and the King were in a car together, returning to Udine from the front, when thousands of troops enveloped them, singing the ‘Internationale’ as they passed. Cadorna turned to his deputy: ‘Why doesn’t someone shoot them?’ Porro shrugged.

Nervous tension kept Rommel awake. Before midnight, a report arrived that Italian troops were moving towards a hamlet higher up the ridge. Enemy reinforcements could prove fatal to his endeavour; Rommel scrambled out of his sleeping bag and led his detachment (now seven companies) up a narrow path to the hamlet. ‘The great disk of the moon shone brightly on the slope, steep as a roof.’

The next Italian line lay above the hamlet, apparently still unoccupied. Rommel decided to encircle the line. ‘I felt that the god of War was once more offering his hand.’ Despite heavy fire from positions on Mount Cragonza, the next hill along the ridge, Rommel’s assault teams climbed around the village unscathed until they looked down on the unsuspecting Italians. ‘We shouted down and told them to surrender. Frightened, the Italian soldiers stared up at us to the rear. Their rifles fell from their hands.’ The Württembergers did not fire a shot. Without pausing, they attacked Cragonza. By 07:15, it was theirs.

It is late morning on the 26th, and Rommel looks up at Hill 1356, the last bump on the ridge before Matajur (1,641 metres). Using a heliograph, he signals a request for German batteries on the other side of the Isonzo to target the hill. As the Italians react to the accurate bombardment, he swings south, turns the Italians’ flank and attacks from the rear. The Italians rapidly withdraw, and Rommel halts. Hundreds of Italian soldiers are standing about on the hilltop, nearly two kilometres away, ‘seemingly irresolute and inactive’. As the crowd swells into thousands, he makes a lightning decision. ‘Since they did not come out fighting, I moved nearer, waving a handkerchief’, with his detachment spread out in echelons behind him. ‘We approached within 1,000 metres and nothing happened.’ The enemy ‘had no intention of fighting although his position was far from hopeless! Had he committed all his forces, he would have crushed my weak detachment.’ Instead, ‘The hostile formation stood there as though petrified and did not budge.’

The Germans have to follow a road through a wooded cleft that separates them from the summit. Rommel and a small team hurry ahead, reducing the Italians’ time to recalculate the odds. Far ahead of his detachment, he breaks cover and walks steadily forward, waving his handkerchief and calling on the Italians to lay down their arms. ‘The mass of men stared at me and did not move. I had the impression that I must not stand still or we were lost.’ When the gap between them has narrowed to 150 metres, the Italians rush forward, throwing away their rifles, shouting ‘

Evviva Germania!

’ They hoist the incredulous Rommel on their shoulders. Both regiments of the Salerno Brigade surrender en masse. Their commander sits by the road with his staff, weeping.

Rommel never understood the Salerno Brigade’s behaviour. Twenty years later, he still marvelled at their surrender, given that ‘even a single machine gun operated by an officer could have saved the situation’. He could not conceive the condition of infantry who had been bundled to the top of a mountain and ordered to defend it to the death against some of the best soldiers in the world, without benefit of proper positions, artillery support, communications or confident leadership. Nor, to judge by his memoir, was he aware of the Italian infantry’s experience since 1915. The seeds of the Salerno Brigade’s defeat were sown long before October 1917.

The Twelfth Battle (Caporetto), October–November 1917

An order arrives from Rommel’s battalion commander: he must pull back to Mount Cragonza. He decides the major must be poorly informed about the situation ahead, and ignores the order. The stakes are too high, and success will justify his disobedience. The conquest of Mount Matajur is relatively simple. He and his men surprise an Italian company from the rear, near the rocky summit, then divert the force on the summit while Rommel circles around. Before the Germans have set up their machine guns for the final assault, the Italians surrender. By 11:40, Matajur is in German hands. In little over two days, Rommel and his men have covered 18 kilometres of ridge, as the crow flies, involving nearly 3,000 metres of ascent, capturing 150 officers and 9,000 men at a cost of 6 dead and 30 wounded. Operating in harmony with the landscape, moving at extraordinary speed, Rommel’s men swooped along the hillsides, weaving across the ridge between Italian strongholds, mopping up resistance as they went, protected as well as empowered by their own momentum.

The Württembergers gaze around at ‘the mighty mountain world’, laid out in radiant sunshine. The last ridges and spurs of the Julian Alps slope down to the lowlands of Friuli and the Veneto. There is Udine amid fertile fields. Far away to the south, ‘the Adriatic glittered’. Like Rommel’s own future. He wore the cross and ribbon of the Blue Max around his neck until the day in 1944 when Hitler, suspecting him of complicity in the so-called generals’ plot, gave him a choice: commit suicide, be buried as a hero and save your family, or be arrested, executed and disgraced. As on the sunlit mountains long before, he did not flinch.

The fine weather, the enemy advance, the Italian rout, and Cadorna’s hesitancy all persisted throughout the 26th. Survivors of the Second Army were in full retreat; vast numbers of men funnelled through the few roads leading westwards, throwing away their weapons, burning whatever could not be carried, blowing up bridges and looting as they went: ‘infantry, alpini, gunners, endlessly’, as one of them remembered. ‘They move on, move on, not saying a word, with only one idea in their head: to reach the lowland, to get away from the nightmare.’ The hillsides below the roads were littered with wagons that had tumbled off the roads; ‘The horses lay still, alive or dead, hooves in the air.’

Civilians joined the stampede; the roads were clogged with carts, often drawn by oxen, piled high with chattels. The British volunteer ambulance unit watched the ‘long dejected stream’ pass along the road to Udine all day: ‘soldiers, guns, endless Red Cross ambulances, women and children, carts with household goods, and always more guns and more soldiers – all going towards the rear’. A British Red Cross volunteer saw how ‘the panic blast ran through the blocked columns – “They’re coming!”’ The command made no apparent effort to control the movement or clear the roads for guns and troops.

Cadorna issued an order of the day, warning that the only choice was victory or death. The harshest means would be used to maintain discipline. ‘Whoever does not feel that he wins or falls with honour on the line of resistance, is not fit to live.’ He elaborated his instructions to the Second and Third Armies for an eventual retreat, and put the Carnia Corps and the Fourth Army on notice to retire beyond the River Piave.

What forced his hand was the loss that evening of Gran Monte, a summit west of Stol. At 02:50 on the 27th, he ordered the Third Army to retreat to the River Tagliamento. The same order went out to the Second Army an hour later. Yet 20 of the Second Army’s divisions were still in reasonable order, withdrawing from the Bainsizza and Gorizia. Cadorna’s priority should have been the safe retirement of these divisions – more than 400,000 men – behind the River Tagliamento. In his mind, however, the Second Army in its entirety was guilty. Perhaps this explains his decision to make the Second Army use only the northern bridges across the Tagliamento, reserving the more accessible routes for the ten divisions of the Third Army, which retreated ‘in good order, unbroken and undefeated’, burning the villages as well as its own ammunition dumps as it went, so that ‘the whole countryside was blazing and exploding’. This question of the bridges was critical, for the bed of the Tagliamento is up to three kilometres wide and the river was high after the rain, hence impassable by foot.

Between the Isonzo and the Tagliamento, the decomposing Second Army was left to its own devices. In the absence of proper plans for a retreat, there was nothing to arrest its fall. As commanding officers melted away in the tumult, key decisions were taken by any officer on hand, using his own impressions and whatever scraps of information came his way. According to a captain who testified to the Caporetto commission, the soldiers appeared to think the war was over; they were on their way home, mostly in high spirits,

as if they had found the

solution to a difficult problem

.

A minor episode described in a letter to the press in 1918 illustrates the point. A lieutenant told the surviving members of his battalion that they would counter-attack soon, orders were on the way. Instead of orders, a sergeant came cycling along the road. When they stopped him and asked what was going on, he said the general and all the other bigwigs had run away.

‘Then we’re going too,’ someone said, and we all shouted ‘That’s right, we have had enough of the war, we’re going home.’ The lieutenant said ‘You’ve gone mad, I’ll shoot you’, but we took his pistol away. We threw our rifles away and started marching to the rear. Soldiers were pouring along the other paths and we told them all we were going home and they should come with us and throw their guns away. I was worried at first, but then I thought I had nothing to lose, I’d have been killed if I’d stayed in the trenches and anything was better than that. And then I felt so angry because I’d put up with everything like a slave till now, I’d never even thought of getting away. But I was happy too, we were all happy, all saying ‘it’s home or prison, but no more war’.

All along the front, variants on this scene convey a sense that a contract had been violated, dissolving the army’s right to command obedience. Nearly 400 years before, in his ‘Exhortation to liberate Italy from the barbarians’, Niccolò Machiavelli had warned his Prince that ‘all-Italian armies’ performed badly ‘because of the weakness of the leaders’ and the unreliability of mercenaries. The best course was ‘to raise a citizen army; for there can be no more loyal, more true, or better troops’. They are even better, he added, ‘when they find themselves under the command of their own prince and honoured and maintained by him’. Machiavelli the great realist would not have been surprised by the size of the bill that Cadorna was served after dishonouring his troops so consistently, and neglecting their maintenance so blatantly, for two and a half years.

On the third day of the offensive, the Austrians and Germans gave the first signs that they would not convert a brilliant success into crushing victory. Demoted in spring 1917 from chief of the general staff to commander on the Tyrol front, Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf had to sit and watch as von Below’s Fourteenth Army turned the tables on the hated enemy. Now he called for reinforcements so he could attack the Italian left flank. At best, Cadorna’s Second, Third and Fourth Armies and Carnia Corps would be trapped behind a line from Asiago to Venice, perhaps forcing Italy to accept an armistice. At the least, the Italians would be too distracted by the new threat to establish viable lines on the River Tagliamento.

Although Conrad’s reasoning was excellent, the Germans were not ready to increase their commitment or let the Austrians pull more divisions from the Eastern Front. Any Habsburg units which might be released by Russia’s virtual withdrawal from the war had to be sent to the Western Front, where the Germans were hard pressed by the British in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). All Conrad got were two divisions and a promise that any others no longer needed on the Isonzo would be sent to the Trentino for an offensive by five divisions, to commence on 10 November. But five divisions were pathetically few for the task, and 10 November would be too late.

Cadorna’s enemies had not expected such a breakthrough. As late as the 29th, Ludendorff stated that German units would not cross the Tagliamento. By this point, Boroević’s First Army (on the Carso) and Second Army (around the Bainsizza) should have been storming after the Italian Third Army. This did not happen, due to bad liaison between commanders, exhaustion, and the temptations of looting. As a result, the Third Army crossed the Tagliamento in good order at the end of October. Both divisions of the Carnia Corps also reached safety with few losses. Von Below would characterise the Austrian Tenth Army, that should have outflanked the Carnia Corps, as not ‘very vigorous in combat’.

On the afternoon of the 27th, the Supreme Command decamped from Udine to Treviso. Cadorna did not leave a deputy to organise the retreat. Was this an oversight or a logical expression of his belief that he was irreplaceable? Or was he punishing soldiers who had, as he believed, freely chosen not to fight? Let the cowards and traitors of the Second Army make their own shameful ways to the Tagliamento; they had forfeited the right to assistance.

By the following morning, the Supreme Command was installed in a palazzo in Treviso, more than 100 kilometres from the front. Over breakfast in his new headquarters, the chief talked about the art and landscape of Umbria, impressing his entourage with his serenity, a mood that presumably owed something to the King’s and the government’s affirmations of complete confidence in his leadership. (Meanwhile the enemy reached the outskirts of Udine, finding them ‘almost deserted with broken windows, plundered shops, dead drunk Italian soldiers and dead citizens’.) Before lunch Cadorna released the daily bulletin, blaming the enemy breakthrough on unnamed units of the Second Army, which had ‘retreated contemptibly without fighting or surrendered ignominiously’. Realising how incendiary these allegations were, the government watered down the text. It was too late: the original version had gone abroad and was already filtering back into Italy.

Late on the 28th, the enemy crossed the prewar border into Italy. The Austrian military bulletin was gleeful: ‘After five days of fighting, all the territory was reconquered that the enemy had laboriously taken in eleven bloody battles, paying for every square kilometre with the lives of 5,400 men.’ The Isonzo front ceased to exist. By the 29th, the Second and Third Armies were being showered with Austrian leaflets about Cadorna’s scandalous bulletin. ‘This is how he repays your valour! You have shed your blood in so many battles, your enemy will always respect you … It is your own generalissimo who dishonours and insults you, simply to excuse himself!’

An order on 31 October authorised any officer to shoot any soldier who was separated from his unit or offered the least resistance. This made a target of ten divisions of the Second Army. The worst abuses occurred near the northern bridges over the Tagliamento, where commanders who had abandoned their men days earlier saw a chance to redeem themselves.

The executions at Codroipo would provide a climactic scene in the only world-famous book about the Italian front: Ernest Hemingway’s

A Farewell to Arms

.

The wooden bridge was nearly three-quarters of a mile across, and the river, that usually ran in narrow channels in the wide stony bed far below the bridge, was close under the wooden planking … No one was talking. They were all trying to get across as soon as they could: thinking only of that. We were almost across. At the far end of the bridge there were officers and carabinieri standing on both sides flashing lights. I saw them silhouetted against the skyline. As we came close to them I saw one of the officers point to a man in the column. A carabiniere went in after him and came out holding the man by the arm … The questioners had all the efficiency, coldness and command of themselves of Italians who are firing and are not being fired on … They were executing officers of the rank of major and above who were separated from their troops … So far they had shot everyone they had questioned.

The narrator is Lieutenant Frederic Henry, an American volunteer with the Second Army ambulance unit. Caught up in the retreat from the Bainsizza, he is arrested on the bridge as a German spy. As he waits his turn with the firing squad, Henry escapes by diving into the river. ‘There were shots when I ran and shots when I came up the first time.’ He is swept downstream, away from the front and out of the war. Immersion in the Tagliamento breaks the spell of his loyalty to Italy. ‘Anger was washed away in the river along with any obligation … I had taken off the stars, but that was for convenience. It was no point of honour. I was not against them. I was through … it was not my show any more.’

The deaths in Hemingway’s chapter on Caporetto involve Italians killing each other. The enemy guns are off-stage, heard but not seen, while German troops are glimpsed from a distance, moving ‘smoothly, almost supernaturally, along’ – a brilliant snapshot of Italian awe. Henry shoots and wounds a sergeant who refuses to obey orders; his driver, a socialist, then finishes the wounded man off (‘I never killed anybody in this war, and all my life I’ve wanted to kill a sergeant’). The driver later deserts to the Austrians, a second driver dies under friendly fire, then there is the scene at the Tagliamento. It is a panorama of internecine brutality and betrayal, devoid of heroism. With the army self-destructing, nothing makes sense except Henry’s passion for an English nurse. Caporetto is much more than a vivid backdrop for a love story: it is an immense allegory of the disillusion that, in Hemingway’s world, everyone faces sooner or later. Henry’s desertion becomes a grand refusal, a

nolo contendere

untainted by cowardice, motivated by a disenchantment so complete that it feels romantic: a new, negative ideal which holds more truth than all the politics and patriotism in the world.