The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 (14 page)

Read The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919 Online

Authors: Mark Thompson

Tags: #Europe, #World War I, #Italy, #20th century history: c 1900 to c 2000, #Military History, #European history, #War & defence operations, #General, #Military - World War I, #1914-1918, #Italy - History, #Europe - Italy, #First World War, #History - Military, #Military, #War, #History

1

They had a slang word for Italian economic migrants:

Katzelmacher

, ‘kitten¬ maker’ or tomcat – sexually promiscuous, with a large family back home, typical of backward peoples. (The same fearful contempt can be heard today when Serbs talk about Albanians from Kosovo.)

2

This hope was also the fear of at least one British Foreign Office mandarin, who predicted in March 1915 that the Treaty of London ‘would drive Dalmatia and the Slav countries into the arms of Austria’.

3

This was the same Duino where the German poet Rilke spent the winter of 1911–12 as the guest of the noble family that still owns the castle. Walking on the battlements one stormy morning in January when ‘the water gleamed as if covered with silver’, Rilke seemed to hear a voice calling from the air: ‘Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?’ This became the first line in the sequence of poems called the

Duino Elegies

(1923).

4

They married in autumn 1915, after the husband sued for divorce and Gina accepted generous terms for access to her children.

SEVEN

Walls of Iron, Clouds of Fire

Let your rapidity be that of the wind, your

compactness that of the forest

.

S

UN

T

ZU

The first principle is, to concentrate as much

as possible. The second principle runs thus

–

to act as swiftly as possible

.

C

ARL VON

C

LAUSEWITZ

The First Battle of the Isonzo

Cadorna’s first full-scale offensive had several objectives.

1

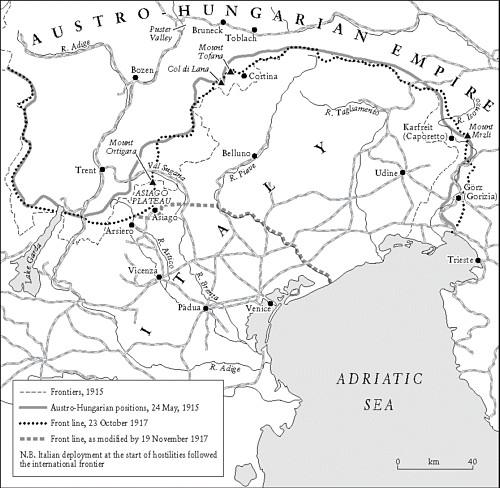

The Second Army was ordered to take the summit of Mount Mrzli while enlarging the bridgehead at Plava, further south, and strengthening its position around Gorizia. These goals had to be pursued vigorously, aiming for success ‘at all costs’. Further south, the Third Army was to push forward on the Carso between Sagrado and Monfalcone. For these tasks, Cadorna committed only 15 of his 35 infantry divisions. The remainder were distributed around the Alpine sectors further west, or held in reserve. While the seven reserve divisions were soon moved to the Isonzo, Cadorna’s original decision showed an ominous reluctance to concentrate his forces, as well as complacency about the prospects of swift success.

At Plava, eight separate attempts to take Hill 383 on 24 June achieved nothing. Operations ground to a halt. The offensive around Gorizia failed due to lack of firepower against the strongest Austrian defences on the front. General Zeidler, who had been decorated for his fortifications in Bosnia and the Tyrol, ensured that his positions could not be seriously damaged by the Italian artillery. The bridgehead was safe as long as the hills of Sabotino and Podgora, looming above the river to the north and west of the town, were unconquered.

The thrust against Mount Mrzli began on 1 July. Two days of bombardment were followed by an infantry attack. But a poor spring had yielded to a wet and squally summer. Torrential rain had turned the 40-degree hillsides into muddy pistes, exposed to Austrian fire. The mist that sometimes lay in the valley bottom afforded the only cover. Infantry on the higher slopes were unable to dig proper trenches in ground that was too muddy or too rocky. The front line slanted up the hill from Tolmein, so the Italians were exposed to flanking fire from the lower Austrian positions. The attacks fizzled out. On Mount Sleme, halfway between Krn and Mrzli, a battalion of the Intra Brigade struggled up to the enemy wire, losing more than 300 men in the process. The commanding officer who had ordered the attack committed suicide. This operation was not mentioned in the daily bulletins issued by the Supreme Command. Indeed, actions on Mrzli during the rest of the year would mostly take place in official obscurity. Other assaults were tried piecemeal, and failed. The Italians took no ground between Krn and Tolmein.

They were discovering that barbed wire was practically insuperable. The Perugia Brigade tried to breach the wire on Podgora with gelignite tubes on 6 July. Enemy fire was so intense that they could not get close to the wire. When the Italians attacked next day, regardless, the Austrians held their fire until the attackers were 30 paces away, while the artillery opened up against the reserves in the rear. No advance was possible. The only sector where Italian operations avoided a fiasco was around the Carso, where the bombardment started on the 23rd, against enemy lines near Sagrado. The troops of the 19th and 20th Divisions drove the Austrians back and got a foothold on Mount San Michele and Mount Sei Busi. An epic struggle for the westernmost heights of the Carso had begun.

Both sides knew the strategic importance of Mount San Michele. A sprawling, inelegant hill with four distinct summits, it fills the angle where the River Vipacco flows into the Isonzo, south of Gorizia. Its summit rises only 250 metres above the plain, but the northern and western slopes are steep. In the east and south, the gradients are much gentler as the hill merges into the Carso plateau. It formed an Austrian salient, protecting Gorizia and the Vipacco valley on one side and the Carso on the other. Without it, the Austrians’ defence on the lower Isonzo might unravel. The Italians were not aware that, on this part of the front, the enemy defences were still shallow. Lacking rock-drills, the Austrians had had time only to hack knee-deep grooves in the rock, then heap rubble and soil into low parapets. With every battalion tasked to prepare 3–5 kilometres of line, they hastily adapted the rocky outcrops, ridges and natural craters, and disguised the barbed wire with branches.

Shortly after midday on 1 July, the Italians advanced from their bridgehead at Sagrado towards the summit of San Michele, with a secondary thrust towards a rounded spur closer to the river, known as Hill 142. Long afterwards, a junior officer in the Pisa Brigade, Renato di Stolfo, described the first attack. He was supposed to lead his platoon armed with a pistol, but there were no pistols, so he had nothing but his dress sabre, with no cutting edge. The day began with a thunderstorm at 06:00, as the men traversed the wooded flanks of the hill. Renato’s waterlogged cape was so heavy that he threw it away. As the men emerged from the woods, the sun rose over the brow of the Carso in front of them, dispersing the clouds; a rainbow arced across the sky.

The men rest for a few hours, trying to dry out. At noon, they form a line, dropping to one knee while the officers stand with sabres drawn. The regimental colours flutter freely. Silence. Then a trumpet sounds, the men bellow ‘Savoy!’ as from one throat, the band strikes up the Royal March. Carrying knapsacks that weigh 35 kilograms, the men attack up the steep slope, in the teeth of accurate fire from positions that the Italians cannot see. An officer brandishing his sabre in his right hand has to use his left hand to stop the scabbard from tripping him up. The men are too heavily laden to move quickly. Renato remembered the scene as a vision of the end of an era: ‘In a whirl of death and glory, within a few moments, the epic Garibaldian style of warfare is crushed and consigned to the shadows of history!’ The regimental music turns discordant, then fades. The officers are bowled down by machine-gun fire while the men crawl for cover on hands and knees. The battle is lost before it begins. The Italians present such a magnificent target, they are bound to fail. A second attack, a few hours later, is aborted when the bombardment falls short, hitting their own line. The afternoon peters out in another rainstorm.

Yet these blundering attacks, repeated less disastrously over the following days, pressed the Austrians harder than the Italians knew. On 4 July, the Austrian commander on the Carso reported that his situation was desperate: the last reserves had been pulled into the line. Control of the plateau edge was threatened. The Duke of Aosta, commanding the Third Army, had asked for reinforcements on the 2nd, but Cadorna was non-committal. By the time extra forces arrived on the afternoon of the 5th, the Austrian crisis was past.

On the southernmost sector, around Monfalcone, the Italian mood was gloomy. The first efforts to drive the Austrians off Mount Cosich and the neighbouring heights (Hills 85 and 121) failed badly. Even worse, the counter-attacks created panic. The Italians were taking steady high losses from the machine guns across the valley. The First Battle found Private Giani Stuparich near the Rocca, on the brow of a hill overlooking the bare, rocky valley. (Today the hillsides are thickly wooded, and a motorway passes along the valley.) He spent his days crouching behind a dry-stone wall reinforced with sandbags, facing a jumble of wire, nauseated by the stink of shit; for the men defecated in the open – anywhere, just to be safe from snipers – turning the pine- scented hillside into a dunghill. The constant rain churned the red clay into soapy, clinging muck. At night, he curled up in the muck and sank into sleep that was violent and black, like death.

The Austrians repelled four attacks on Hill 121. A fifth attempt fails when the company assails the wrong part of the line, where there are no gaps in the wire. Nothing goes well, and the forced passivity is a burden. When their commanding officer asks for volunteers to blow a hole in the enemy wire, Giani and his brother Carlo step forward. There is six days’ leave for the team that succeeds, but they are not after this reward; they are Habsburg Italians, volunteers from Trieste. ‘We are in this war because we wanted it; how can we hide behind silence?’ That night, they creep towards the enemy lines carrying gelignite tubes. Unusually, the party succeeds in breaching the wire, but the gaps are repaired before the Italians can exploit them. Giani’s spirits sink when the Austrians bombard Monfalcone; at this early stage of the fighting, the targeting of civilian areas shocks the idealistic volunteer.

The first full-scale attack against Cosich began at 02:30 on 30 June, in torrential rain. Austrian counter-battery fire silenced the Italian guns. Yet the dawn assault was not abandoned, as another veteran recalled: ‘All at once the cry goes up, with nothing human about it, “Savoy! Savoy!” – which the valleys echo up to the sky, as if invoking God’s witness to their martyrdom. But a wall of iron stops them, a cloud of fire envelops them.’

The last veteran of the first battle on the Isonzo was alive and well in a leafy suburb of Rome in 2004. Born in December 1894, Carlo Orelli was conscripted on 24 May 1915 and sent off to the Carso after notional training. Nearly 90 years later, he sat in sharp sunlight beside the opened shutters of his bedroom window. He was very still under his dressing gown, silk scarf and cloth cap; only an index finger moved, tracing a pattern on his leg. His blue eyes were filmy.

Orelli was a Socialist, but in the debate over intervention that raged in Italy in 1914–15, he switched sides, like Mussolini. ‘Supposedly it was all secret, but everyone knew the war was coming.’ The troop train left from Naples.

It was a lovely day, I remember it well. A great blue sky. We thought we were going to the front to take Trento and Trieste, which were under Austria. We had gone to war to conquer those territories, which were Italian. Austria had taken them from us. Then we would go forward, forward … We expected a short war, not one that would last so many years.

Words came awkwardly, in short breaths, as memories surfaced.

Was it a war of conquest or liberation? ‘Liberation,’ he said firmly. ‘We were not taking what was theirs.’ Were the troops eager for war? ‘Not enthusiastic, no! They thought it was a fine thing to reconquer our lands,

le terre nostre

, but they weren’t prepared for what faced them at the front.’

He was a non-commissioned officer in the 3rd Company of the Siena Brigade. Arriving at Sagrado at the end of May in cotton uniforms and berets, with boots of light canvas, the Italians pillaged the linen they found in the houses (‘Austrian stuff’, said Orelli), as well as blocks of sugar that were left in a factory yard. The men were mostly from Calabria, in the south. ‘You could not understand a word they said. Good illiterate peasants. I wrote their letters home for them. Oh, you people today don’t know how backwards Italy was in those times. They couldn’t read or write, but they never complained. They died in silence.’ He did not blame the army for poor training. ‘War is not something you teach, you do it and that’s all. Attack, fire, take cover when you have to. That’s it. And then bring in the dead.’

The Italians were hugely disadvantaged at the outset. ‘The Austrians had fine covered trenches, with bunkers. They shot at us from loopholes, while we were in shallow holes, ordered to charge the enemy with bayonets. It was attacks, attacks all the time, from dawn to dusk.’ The Austrians on Mount San Michele did not have to shoot much. ‘They only had to hold their positions and wait to kill us in the open.’

While the Austrian positions on San Michele during the first battle were not really much better (though they soon became so), Orelli’s recollection is true to the Italians’ sense of being desperately unprepared. And he was correct about the difference in firepower.

You cannot have any idea what an Austrian 420-millimetre howitzer sounds like. Quite different from what you would expect. It’s not like in a film. It was too far away to make a boom. It was more of a rumble, a distant roar, then a whistling that grew louder and louder the closer it came. Then we knew the shell was about to hit. It did not always explode at once. Sometimes it didn’t explode at all. That’s the lottery of death.

The Italians did not have any 420s, or any 305s for that matter. They had a few 149-millimetre guns at Sagrado, targeting those Habsburg trenches.

The Italians’ battle cry was ‘Savoy!’, while the enemy screamed ‘Hurrah!’, or ‘Živila Austrija!’ (‘Long live Austria!’) if they were Croatians or Bosnians. On Mount San Michele and Mount Sei Busi, the armies were 100 or 200 metres apart. There was a ‘tacit agreement’ not to make each other’s lives even worse than they had to be. Sniping was suspended between attacks.

Did you hate the enemy?

No, no, no! They were under orders, just as we were. War is war, if you try to kill me I’ll try to kill you, but there was no hatred. When we took prisoners, they were sent to work the land in Italy for the rest of the war. There was no mistreatment. It was the same with Italians taken prisoner. The Austrians, who had everything, offered our men fine food, because they knew we had nothing. We asked them to taste it first, in case it was poisoned, but it was all good stuff.

‘It was a war without hatred,’ he repeated, ‘not like nowadays, with all this …’ His attention drifted, following some elusive connection. The pause lengthened. ‘There’s war everywhere now,’ he announced. ‘A nation is dying today – the one led by that general with the beard, a prisoner now. What’s his name?’ He meant Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi dictator, lately captured but not yet executed.

Lightly wounded in the First Battle, Orelli was riddled with shrapnel in the Second. By this point, only 25 men of the 330 who had gone up to the line with him in May were still unharmed. He left the front in September 1915, never to return, so the attitudes that crystallised in him – including the conviction that gentlemanly conduct had persisted – reflected the first months of fighting. Orelli had not seen the spiral down into brutality and perhaps did not believe it ever occurred.