The Way Into Chaos (53 page)

Read The Way Into Chaos Online

Authors: Harry Connolly

None of the other refugees had someone to meet them or a red cloth to tie to their upper arm. They were herded at spear point toward a long, muddy pit. Spears stood guard at the near end and, Tejohn assumed, at the far end as well. The sides of the pit were braced with more logs, and bored archers stood along the top.

“Where are you taking us?” the ferryman demanded, and received a rap from the edge of a shield to silence him.

They passed below a line of heads mounted on spears. All had rotten until they were barely recognizable as human.

A dozen refugees were penned like sheep while the blacksmith’s family was brought before a bored-looking official seated at a long wooden table. Beside him stood an overweight soldier with a tall red comb. Behind both of them stood another dozen spears.

Tejohn hung back beside the fisherwoman. “What’s happening?” he asked in a low voice. “I can’t see that far.”

Her answer was so quiet, he almost couldn’t hear it. “They’re charging us for admission to the city.” She shuffled her feet, glancing back toward the wooden gate as though she wanted to get back onto the road, but she didn’t have the courage to leave the pen. “I don’t have more than a few copper ins.”

It had been a while since Tejohn had reason to think about money. It was one of the privileges of his place in the palace--he thought for the first time about the strongbox in his rooms back in the Morning City. It was heavy with silver bolds and even a few gold pinches. Right now he wasn’t carrying so much as a tin speck.

The blacksmith’s family was led to a second pen, their shoulders slumped. “They even took his tools,” the fisherwoman said.

That was bad and they all knew it. The ferry folk were brought forward next, and the father tried to bluster through the interview, talking in a loud voice about the important news he brought from the south and how he was certain his tyrship’s good fighting men would want to hear it. But when it came time to open his purse to the officials, he demanded they tell him the fee first.

For his trouble, one of the good fighting men he’d been flattering rammed a spear into his guts. While his family knelt in the mud and wailed, his body was stripped and thrown into a cart. There were no other corpses in there, but the hour was early.

The other family members--wife, sons, daughters, grandmothers--had everything of value taken from them, then they were penned with the smith. Tejohn shut his eyes and prayed that The Great Way would look after his own family and allow them to stay on the path.

Just before she was taken away, the fisherwoman took Tejohn’s hand and pressed a single coin into it. “Better to have something for them to take, I think, since they’re going to take everything.”

It would have been an insult to refuse. “Song will remember,” Tejohn said.

“The Little Spinner never slows,” she said as she was led away. It was a saying he’d heard often from farm folk when he was young, but had never heard in the palace.

Everything changes.

When it was his turn, he gave his name as Ondel Ulstrik, a farmhand from just downslope of the spur. He told them the farmers were holed up on their property and had no supplies to spare for hired men.

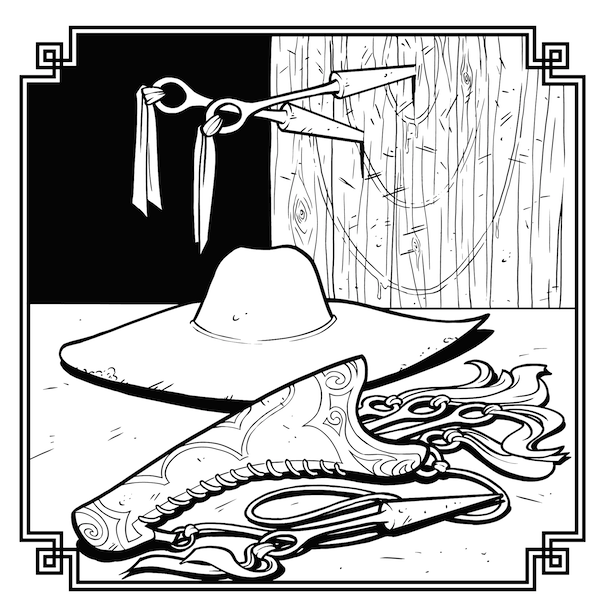

The official told him weapons were not permitted inside the city and took his knife. They demanded an accounting of his personal property and rolled their eyes when he held out the copper ins. Tejohn could feel the soldiers looking him over; he made sure to slump his shoulders and keep his expression slack.

“Entrance to the city will cost you two ins,” the official said with a bored expression. “Those boots will cover the balance.”

His boots were worth more than an ins, but he took them off without a fuss and gave them over.

The mud was cold against his bare feet. He joined the others in the second pen. No one could speak over the wailing of the ferry family--the grandmother’s pleas that they be allowed to bury the man’s body were ignored.

As they were led up the ramp at the far end of the pit, a pair of soldiers pressed tiny loaves of bread into their hands. They were insistent that everyone take one because Tyr Finstel wanted no starvation within his walls. Tejohn reluctantly accepted.

When they came out of the pit into a small building, they were told there was a charge of six specks for the bread. The ferryman’s widow tried to pay with a silver bold she’d hidden on her person, but she was beaten and given six years of servitude for Concealing Assets.

No one else had a single speck to offer, let alone six. All of them, Tejohn included, were tattooed and sentenced to a year of servitude in the name King Shunzik Finstel, ruler of Ussmajil.

Chapter 25

“It is there, ape. Just down in that ravine.”

Chik, the insect warrior they had captured, had taken to calling them

apes

. In his opinion, Cazia, Ivy, and Kinz were the ugliest creatures he’d ever seen, and he occasionally insisted that every word of their conversation was a trick being played on him by one of his people’s many enemies. He was convinced the translation stone simulated their conversation, because only insect brains were complex enough to understand abstract concepts.

Kinz was so irritated by these frequent pronouncements she sometimes seemed on the verge of violence. Ivy treated the creature like one of her subjects, as if it needed nothing more than tolerant instruction.

Cazia was beyond those sorts of emotions. She felt nothing more than an intense curiosity about the creature--especially the way the small frills at the base of its skull vented one odor after another, which her blue jewel dutifully translated into a long string of boasts about himself, his queen, and the mighty empire of the Tilkilit people.

They had spent most of the day and part of the night creeping through a fog-shrouded forest with Chik guiding the way. Kinz suspected the creature was leading them in circles, but Ivy pointed out that many of the trees had a stringy red moss on the northern side. It would have made sense for Chik to take them in circles until they found another one of their patrols, but it was clear they were traveling in a straight line.

Whether he was leading them where they wanted to go was a different question. Chik claimed to be taking them to the Door in the Mountain. According to him, the eagles had come through this door, and so had he.

“This is where our scout patrols, the swiftest and most worthy, chosen by Queen Sheshoorakolm herself, Ruler of the Depths of Glory and Stone of Might, She who birthed a billion warriors, the All-Blind, All-Knowing Mother of the Tilkilit people, first made entry into this land.”

He gestured toward a place where the grass gave way to scraggly bushes and the ground rose steeply into bare, stony ridges. A warm wind blew from between two of them, thinning the fog to nothing. They could not advance without coming out of the cover of the trees.

Chik kept talking. “Seventy-second into this land, Chik Strong Eyes, Bearer of Lance and Mace, Master of Secret Ways—”

“Enough,” Cazia said. She was holding the blue stone and, although Chik was unable to understand her, he recognized her tone. He clicked his claws twice to indicate his contempt, then fell silent.

“He never shuts up, does he?” Kinz asked. She had held the stone for a few minutes while Cazia had taken and discarded Chik’s weapons, a copper-bladed spear, a pouch of smooth, dark stones without a sling, and a flanged club worn where a human might wear a dagger. It was the only time Kinz had listened to him, and she’d refused to take the stone since.

“I think I understand,” Cazia said. When did her voice get so flat? “They talk in smells, and all this information is released in a single stink. Each odor is complicated by a dozen substances, see? But for us, each piece of information has to be turned into a word and strung out in long phrases. That’s why he’s insulted that we shorten his name, because it’s not actually shorter to him, just simplified.”

“Give him the stone,” Ivy said. “I will explain this to him.”

“No, do not,” Kinz said. “It will just give him another opportunity to tell us how superior he is.”

Kinz, who had signed on to this mission as a servant, was now giving orders. It would have bothered Cazia once.

She picked up the blue stone again. In her odd state, the warrior’s words seemed to echo in her head. Had she used it for an hour yet? The other girls knew to warn her if she started talking gibberish, but what if the effect came on suddenly? Would going hollow increase the danger or reduce it? Or was this another of Doctor Twofin’s scare stories? So many interesting questions.

A shadow passed over the ravine floor. A raptor. Cazia and the others were well hidden among the trees, but they retreated to a dense stand anyway.

She set the stone down beside Chik; they’d already learned it wouldn’t work if both of them held it at the same time. The creature picked it up with its clumsy claws, and Cazia spoke. “No names, understand? Just tell us how long you have been here and where you come from.”

He set it down and she picked it up. “My people have been here for two hundred plus sixteen plus three days, although I suspect you apes will not be able to understand a number of such complexity. We fight, always, without reinforcements, and are unable to find deeper soil. Our empire--which has a name that would boggle your mammalian brains--is far to the south of here, where the weather is warmer and the soil, grass, and trees are orange. A warrior could march eastward and return years later from the west, without ever setting foot outside our empire.”

Cazia repeated that and Ivy became convinced Chik came from a globe-spanning continent beyond the sea. Cazia thought it was more likely that he was lying to make himself seem important, and Kinz refused to accept that the world could be round.

It was midday. Cazia decided they shouldn’t risk the translation stone any more. Kinz and Ivy slipped out of the grove to find a squirrel or something to eat, and Cazia tried to create a basic sign language with their prisoner, just as Ivy’s people had with the serpents, but he had no interest in that at all.

Chik ate almost continually, taking tiny portions of crusty stuff from a pouch at its shoulder. Kinz had initially demanded he turn his rations over to them, but he warned them he could only speak if he had access to his food, and they relented.

The girls took turns standing guard over him through the night. Cazia would have liked some rope to tie his legs with, but they hadn’t brought any. Chik, although smaller than Ivy, was stronger than any of them; woven grasses wouldn’t do the trick.

In the middle of the night, Cazia woke to voices. Ivy was explaining the history of her bow--that it had been made for her by her mother as per family tradition. They were just shapes in the darkness, sitting as far from each other as visibility of the thinned-out fog allowed.

“What’s going on?” Cazia interrupted.

“Chik doesn’t understand where my bow came from,” Ivy answered. “I keep telling him that the women in my family have been making them for generations, but he keeps asking who taught us.”

“You’re wasting your breath,” Cazia said. “He’s asking what non-human creature taught you. He doesn’t believe

apes

are smart enough to create them, and you’re never going to get past that contempt.”

Chik shifted his position slightly, and Cazia knew what he was going to do before he did it. The blue jewel landed beside her in the wet dirt, and it only took a few moments for her to find it and pick it up.

“How did you apes get into this valley?” Chik asked, once again posing the question they’d agreed to never answer. “You have no wings. You have no burrowing tools. Mighty serpents make the water impassable. You certainly could not climb over the mountains with the smooth cliffs and Great Terror above.” The

Great Terror

were the huge eagles.

The old Cazia would have said the Great Terror regularly let her people ride on their backs in exchange for pretty shells or something equally snide, but she’d burned that part of herself away. So instead, she tossed the jewel to him and asked him a question in return. “How did your people come to the Door in the Mountain and this valley?”

He returned the jewel and answered, “We were brought here by the Great Way.”

Cazia couldn’t sleep for the rest of the night.

In the dark, tears flowed down her cheeks for no reason she could understand, and they stopped for no reason, too. The alien sorrow and longing ebbed and flowed; she could do nothing but ride it out and wonder what it all meant.