The Virgin Cure (17 page)

As I went to leave, Mr. Birnbaum came in with a young woman who was unfastening her cloak to reveal large, deep pockets in its lining. Reaching into one of them she pulled out a silver comb. “There’s plenty more where that come from,” she boasted, teasing Mr. Birnbaum with a wink.

I nodded to them as I headed out the door. Then, slipping my hand inside my pocket so I could feel my share of Nestor’s plan, I found four quarters, three nickels and a dime—tiny and thin and mine.

The vagrant and neglected children of the city, if placed in a double file, three feet apart, would make a procession eight miles long. From Castle Garden to Harlem Meer. From Wall Street to Fort Washington. Nearly thirty-thousand little souls.

—DR. SADIE FONDA

,

The Annual Report of The New York

Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children

, 1871

A

nickel would buy a plank in a crowded basement. Six cents would buy a night in the girls’ Christian lodging house on St. Mark’s Place. It was four cents more if you wanted a plate of pork and beans. I wouldn’t have minded spending the four cents, but then, while my mouth was full, they’d go and tell me I was nothing but a sack of sin.

The lodging house ladies called every girl they met an orphan. It made perfect sense to them, even if it wasn’t true. If a girl had no family, then they had an excuse to catch her and treat her soul like it needed fixing. As soon as all those wretched

r

’s started coming from between their lips

—refuge, reform, religion

—I would be out the door. The lodging house ladies could keep their prayers

and

their pork and beans.

For three pennies I could get a place on a floor.

Tin on the door, open floor

. A cup, a can on a string, a colander, an old kettle hanging on the latch—those were the things that told any wanderer they’d found a house with room to spare, a place to lay their head for the night. Even Mama had tied Papa’s dented mug to the handle of our door whenever we needed to collect extra pennies to make rent.

We’d get as many as a dozen women in one night, some with children in tow. In the morning, I’d see them sleeping on the floor, or leaning with their eyes closed against the walls of our front room. Even asleep, there was sadness in their faces. Maybe they had no home, or the mister was angry, or somebody had held tight to the handle of an iron skillet while saying something they shouldn’t have. Mama didn’t ask. All that mattered was that they had three pennies and no place else to go.

The money I’d gotten from Mrs. Birnbaum bought food, a bit of time off the street, a kerchief for my shorn head, a knife for my pocket and a new pair of boots. The kerchief was a square of Turkey-red calico, and the knife, although rusty and dull, made me feel secure. The boots were second-hand, of course, from a cobbler’s stall at Tompkins Market. I’d picked them off one of the long poles the shoe man had propped up along the back of his place. He slid fourteen pairs off the end of the ladies’ stick before he got to the ones I wanted. They were black with red leather at the toes, and while not pretty, they fit me far better than the pair Caroline had given me to wear at Mrs. Wentworth’s. I’d gladly traded that pair for the cobbler’s, sure that the new ones would be sturdy enough to last me through the winter.

October arrived along with empty pockets and the need to think ahead with every step. Mama had always said October was her favourite month of the year. “Another fine month ending in an

r

, safe to eat all the oysters you want without having to worry about a troubled gut.” I’d loved autumn for different reasons—for sunsets and candlelight coming sooner every evening, and the way people forgot all the terrible things that summer made them do—but this year, October’s uncertainty, its days of rain with no end in sight, and first fires in dirty chimneys sending homes up in flames, worried me to no end.

Hot-corn girls sang on every corner, their baskets perched on their hips.

Hot Corn! Hot Corn!

Here’s your lily white corn!

All you that’s got money

,

poor me that’s got none

,

come buy my hot corn

,

and let me go home!

They were sweet-looking girls around my age and I hoped I could become one of them. I envied their steady pay and their ability to carry a tune while being badgered by sporting men and roughs.

“I’ll come home with you!”

“I got some hot corn for ya, girlie!”

“How about some butter for that

corn?”

The men gladly paid their three cents an ear, but it wasn’t the corn, harvested dry and bloated back to life by boiling, that they were after. Blushing cheeks, hot with embarrassment, were what they craved.

Arnica Liniment

.

Add to 1 pint sweet oil, 2 table-spoonfuls tincture of arnica; or the leaves may be heated in the oil over a slow fire. Good for wounds, bruises, stiff joints, rheumatism and all injuries.

I went to Mr. Pauley, the man who hired the girls to sell his corn, but he had no interest in taking me on. My kerchief covered my hacked-off hair, but the bruises hadn’t yet faded from my face. He took one look at me and told me to go away. “I need girls with fresh faces, not pathetic-looking waifs.”

Mr. Finnegan, the flower girls’ boss, said the same.

My first night on Chrystie Street, I slept on the roof of Mama’s building, relying on its bricks and mortar to give much-needed warmth in the chilly autumn night. I knew I should’ve gone away from there, but I found great comfort in being close to the place I’d once called home. In summers past, Mama had let me tent on the roof. I’d used piles of newspaper for my mattress, and an old sheet thrown over a wire as a shelter for my head. I knew where the handholds were in the brick on the side of the building, which ones were loose and which ones weren’t. I knew just where to catch the fire escapes to make it the rest of the way to the top.

That night I spotted a wooden barrel on the next building over. Making a bridge with a stray board across the space between the two rooftops, I rolled the barrel back to my spot. Putting bricks on either side to keep it steady, I made my nest inside the thing by lining the bottom with newspapers and mouldy burlap bags I found in the rubbish. Other people came and went from the roof, mostly boys looking for a spot of their own for the night. The knife I’d bought from the junk man wasn’t sharp enough to do much harm, so I kept a length of board by my side to use as a weapon. It had three nails sticking from one end and I named it Pride, hoping it would swing true before a fall.

In the mornings, I’d sit at the edge of the roof, watching for things to start squirming under the garbage that overflowed from the bins along the street. I’d make guesses as to whether something was a rat, a cat or a baby. Even if a bin was a little too far away, I could still make a pretty good guess as to what was inside it. A rat will wiggle and crawl all around, but then hold dead still if it’s startled. A cat will dig and stop, then dig and stop, keeping at whatever it’s after for quite a long time. A small child almost always goes straight in, trying to reach one precious thing. If they can’t get to it, or can’t find their way back out, they break down and cry.

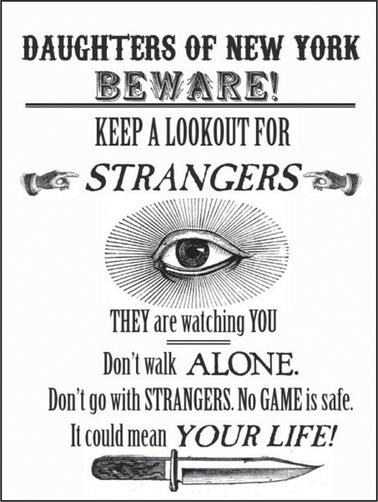

I spent my days begging on the Bowery, only a short walk from Chrystie Street. Mama had always discouraged me from going there, saying it was a terrible place for a girl or anyone else for that matter. “If you’ve money in your pocket when you arrive, you can be sure it’ll be gone when you leave.” But I didn’t have any money left to lose, so the thieves and temptations of the lively, broad thoroughfare didn’t worry me.

Every building on the Bowery was flashy and loud. There were dance halls, third-class hotels, variety theatres, concert saloons and any number of amusements. Shooting galleries opened up to full view, shadow men and beasts waiting under striped awnings to get shot through the heart. One popular spot boasted a cut-out of a lion that let out an awful roar when fatally wounded. The place was always busy, scores of barefoot boys lined up to try their luck. A shiny knife would be their prize if they hit the bull’s-eye painted on the snarling creature’s chest.

Ragged organ grinders scolded their monkeys for chattering too much. Sad-faced boys sat on stoops, leaning on banjos or harps, plucking one string at a time and holding out their hats for a reward. “Copper, sir? Spare a penny?” they cried. An old man played the fiddle and danced, his eyes squinted shut to make people think he was blind. He could play just about any tune anyone asked of him, making his fiddle sound like ten. When he was finished, he’d laugh and smile and talk to himself, his mouth all gummy—not a single tooth in his head. I thought if anyone deserved charity, it was him. I promised myself that someday when I had money enough to share, I’d find him and put at least a quarter in his hat.

It takes equal parts of desperation and courage to beg well. Passersby look at you and think there must be laziness in your blood, that you’ve a secret sense of ease and glee with every penny that comes your way. Oh, if only that were so. There were as many kinds of beggars on the Bowery as there were storefronts, each one—man, woman or child—merely looking for a way to get through to tomorrow.

Some were lonely grandmothers worse off than Mrs. Riordan. Some were soldiers who’d been injured in the war. Most of them were missing at least one limb. Mr. Dillibough’s right leg was gone all the way to his thigh. He had a polished wooden replacement the government had given him to help him get along, but he left it at home when he was working the Bowery because, as he liked to say, “Empty trouser legs have more appeal.”