The Vikings: A Very Short Introduction (18 page)

Read The Vikings: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Julian D. Richards

Tags: #History, #General, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Europe, #Medieval

William Morris, designer, author, and revolutionary social-ventin

ist, developed a passion for medieval Scandinavia while an

g th

undergraduate at Oxford. Morris identified with the Norse

e Vi

heroes and learnt Icelandic from Eiríkr Magnússon, with

kin

whom he translated a number of sagas. His two voyages to

gs

Iceland, in 1871 and 1873, were highly influential on his art,

poetry, and politics. His Icelandic epic poem,

Sigurd the

Volsung

, was published in 1876. Morris’s friends in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, particularly Burne-Jones and Ford

Madox Brown, also had romantic Viking themes in their

paintings. For Morris, however, the Norsemen were hard-working socialists. As a founding member of the Socialist

League, Morris was at the centre of political unrest in Britain

in 1886–7. His visionary novel

News from Nowhere

became

an essential socialist text and his influence runs down to

Clement Atlee and the post-war welfare state. As late as the

1970s his views on the environment led him to be recognized

as a founding father of green politics too.

121

William Collingwood (1854–1932)

As a student reading Greats at Oxford, William Collingwood

came under the patronage of John Ruskin. After studying at

the Slade between 1876 and 1878, he became a research

assistant and secretary to Ruskin, travelling with him, and

living close by in Coniston. During the 1890s Collingwood

developed his painting skills but also published regularly

in the Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland

Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, of which he was to

become Editor and then President. Collingwood was drawn

to Norse legend and felt that the Lake District represented

a Norse landscape. He wrote a series of novels, including

Thorstein of the Mere

(1895) and

The Bondwoman

(1896) set

sg

against that background. In 1897 he visited Iceland and later

kin

published, with Jon Stefansson, his

Pilgrimage to the

e Vi

Sagasteads of Iceland

. He was a member of the Viking Club,

Th

and served as its president. He became particularly interested in the artistic aspects of Norse culture in England, and

devoted himself to drawing and cataloguing the stone sculpture. This was published shortly before his death as

North-

umbrian Crosses of the pre-Norman Age

(1927), perhaps his

most important work.

Sir Walter Scott was fascinated by the Norse history of Scotland and set the opening scene of his novel

The Pirate

(1828) at the Shetland site he christened Jarlshof. A host of children’s books were published, notably Ballantine’s

Erling the Bold

(1869) and Sabine Baring-Gould’s

Grettir the Outlaw

(1890). Meanwhile historians were also writing academic books on Vikings. In 1841 Thomas Carlyle published

On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in

History

in which he saw Oðinn as the emblem of the strong inspired 122

leader, and in 1875 he produced

The Early Kings of

Norway.

In general, however, when Vikings were described by English historians, they often appeared as treacherous barbarians, and as foils for the great hero King Ælfred. It is not surprising that the German-speaking rulers of Great Britain and their supporters should look to the Anglo-Saxons as their forebears. For the English, then as now, the Anglo-Saxons were the ancestral

us

, while the Vikings were

them

. The Scandinavians only settled in part of England and the subsequent ‘reconquest’ made the whole episode seem like a temporary blip in the development of a unified English kingdom and, unlike the Norman Conquest, the Viking invasions created no long-term constitutional changes.

R

Furthermore, the Vikings in England failed to produce a historian;

ein

v

their deeds were known solely through the eyes of the West Saxon

entin

chroniclers, and so long as later historians accepted this

g th

propaganda as fact, the Vikings were guaranteed short shrift. It was

e Vi

Ælfred, Victorian school children were taught, who unified the

kin

g

nation, saved the English from the invaders, and founded the

s

British Navy, while mixing with the common people with ease, despite burning their cakes. On the other hand, the Vikings had also to be portrayed as worthy adversaries, and by the end of the 19th century were almost seen as benefactors of the lands they raided.

They were equated with nobility of adventure and in many places were seen as the founders of democracy.

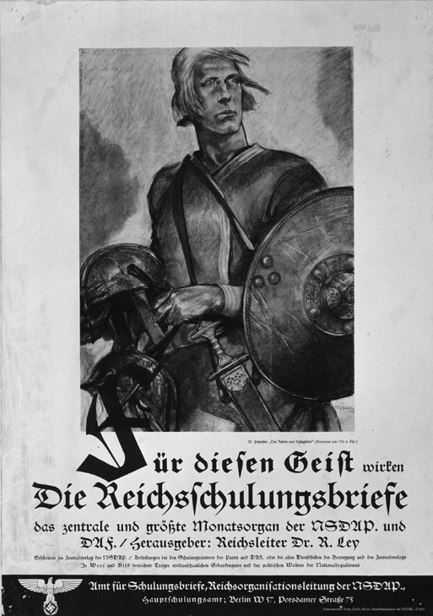

Vikings and Nazis

In Germany under the Nazis a more sinister interpretation of Vikings developed. During the late 19th century Wagnerian mystique was merged with Nietzsche’s elitist philosophy of the superman.

Some Germans began to see themselves as the

Herrenwolk

, or master race. Vikings became their own racial forebears and role models, destined to defeat their inferiors in other countries.

123

After Germany’s humiliating defeat in the First World War, these ideas were turned into party politics by Hitler and his followers. The Nazis attempted to close ranks with the so-called Aryan people of Scandinavia. When they came to power in 1933 they began a crusade against modern ‘decadent’ culture, systematically replacing it with their own version of Aryan culture, based on Vikings, Old Norse mythology, Wagner, and German peasant culture. The Vikings became part of the fair-haired, blue-eyed, clean-living ideal of the National Socialist Party. At its most extreme, Nazism intended to replace Christianity with the old paganism of the Germanic gods. The excavations at Hedeby in the 1930s were strongly backed by the political apparatus of the German state, which wished to emphasize a unity with the people of Scandinavia which had little foundation in reality.

Similar ideals were adopted by right-wing groups in the Scandinavian countries. The Norwegian National Socialist party

sg

used the barrow cemetery at Borre, Vestfold, in Norway, as a

kin

backdrop for political rallies from 1935 to 1944:

e Vi

Th

We gather here because the people who united Norway in one kingdom were buried here. These people carried the name of Norway all over the world. It was these people who founded states in Russia and, in a certain sense, also the British Empire.

Northern European Neo-Nazi groups continue to seek intellectual justification by perverting aspects of pre-Christian religious beliefs and appropriating Viking sites, notably those with ceremonial associations, such as Old Uppsala.

Fakes and forgeries in the United States

Amongst many of the modern inhabitants of North America the quest for European ancestry is an important part of their cultural identity. Many have seized upon finds that purport to show pre-Columbian European settlement, and some have not stopped short of inventing them.

124

Rein

ventin

g th

e Vi

kin

gs

17. Second World War recruitment poster

In 1879 a Swedish emigrant arrived in Douglas County in Minnesota and settled in the town of Kensington. In 1898 he announced that when digging deep in his fields he had found a large 125

rune stone,

c

.0.8m in height, between the roots of a large poplar tree. The text purported to say:

8 Goths and 22 Norwegians on a voyage of exploration west of Vinland. One day’s journey north of this stone we camped close to two rocky inlets. One day we went out fishing and on our return found the dead bodies of ten of our men, red with blood. AVM

deliver us from evil. 14 days journey away from this island, then men are keeping watch over our ships. 1362.

Prominent Scandinavian and American runologists immediately declared it to be a fake as the runes were nonsense. Nonetheless it was exhibited in the Smithsonian Museum as a genuine artefact in 1948–53. By 1950 no fewer than 24 runic inscriptions were cited as evidence for Norse settlement in North America. Subsequently the Kensington runes were proved to have been carved with a chisel of a

s

type sold in Minnesota at the end of last century and the farmer was

g

kin

found to be an amateur runologist with a collection of books on

e Vi

runes. The Runestone Museum in Alexandria, however, still

Th

features the Kensington stone as its prize exhibit.

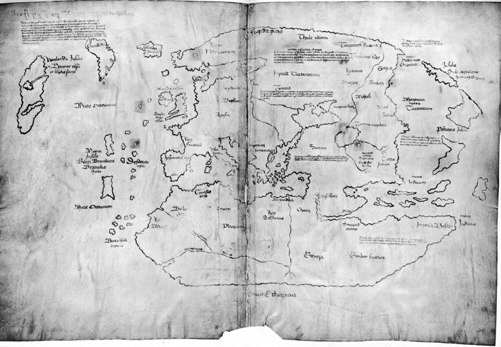

The authenticity of the so-called Vinland map has been even more bitterly contested. The map was published by Yale University in 1965, having been bought on their behalf, reputedly for one million dollars. It comprises a pen and ink map of the world on thin parchment. The representation of the Old World is consistent with maps of the Middle Ages, and follows the custom of placing some fictional islands in the Atlantic. It also includes, however, two large islands in the North Atlantic: Greenland, and a second island labelled ‘Vinland, discovered by Bjarni and Leif in company’. The map was supposedly created in Germany or Switzerland, probably in association with the Council of Basle, which met 1431–49.

In fact, there are several reasons for regarding it as a forgery. First, Greenland is depicted as an island, although this was not discovered until 1902. Second, the depiction of the eastern North Atlantic is 126

18. The Vinland map is a pen and ink drawing of the world purporting to have been made in the 15th

century: the land labelled Vinland is shown top left

based upon 16th-century Portuguese maps that only gained public attention in the late 19th century. Finally, the ink was tested in a Chicago laboratory and found to contain titanium pigment not available before 1917 at the earliest. In fact, this ink is now falling off the map. However, like all good forgeries the Vinland map has refused to go away. In 1986 the ink was reanalysed at the University of California. There it was declared that only microscopic amounts of titanium were present and that both ink and parchment were consistent with a 15th-century origin. One of the interesting features of both the Kensington rune stone and the Vinland map is that, for those people who want to believe in them, scientific evidence can be dismissed as unimportant, or beaten into submission.

As is generally the case in the writing of history there are political undertones to all of this. Earlier attempts to find ancestral

s

Europeans in America did so at the expense of native North

g

kin

Americans. Indigenous monumental architectural achievements

e Vi

could not be accepted as the product of barbarian cultures which

Th

had been all but exterminated by the white man, and it was important to establish a prior claim for 19th-century settlers.

Stone structures and burial mounds were cited as evidence of Viking activity, rather than accepted as the work of a sophisticated palaeo-indian or Inuit culture. Scandinavian finds were found further and further down the eastern seaboard of the United States, although they were still concentrated in areas of high 19th-century Scandinavian immigration.

Today the message has changed, but is just as loaded. Despite the fact that the only attested Viking site is at L’Anse aux Meadows (p. 110), firmly in Canada, in 2000 the Smithsonian Institution in Washington staged a major Viking exhibition, to mark the 1000th anniversary of Leif Eriksson’s historic voyage. The preface to the book which accompanied the exhibition (Fitzhugh and Ward 2000) was by Hilary Clinton. The First Lady noted that Viking women were active participants in politics and religion, while the 128