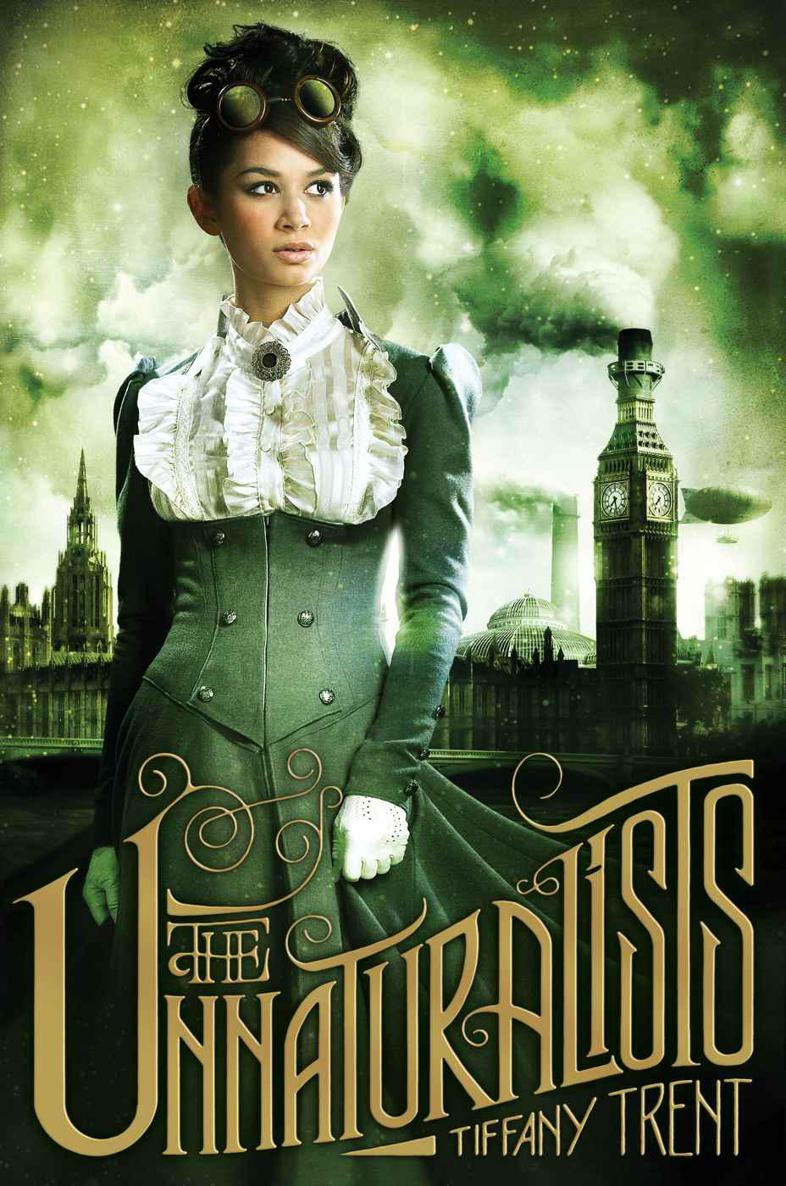

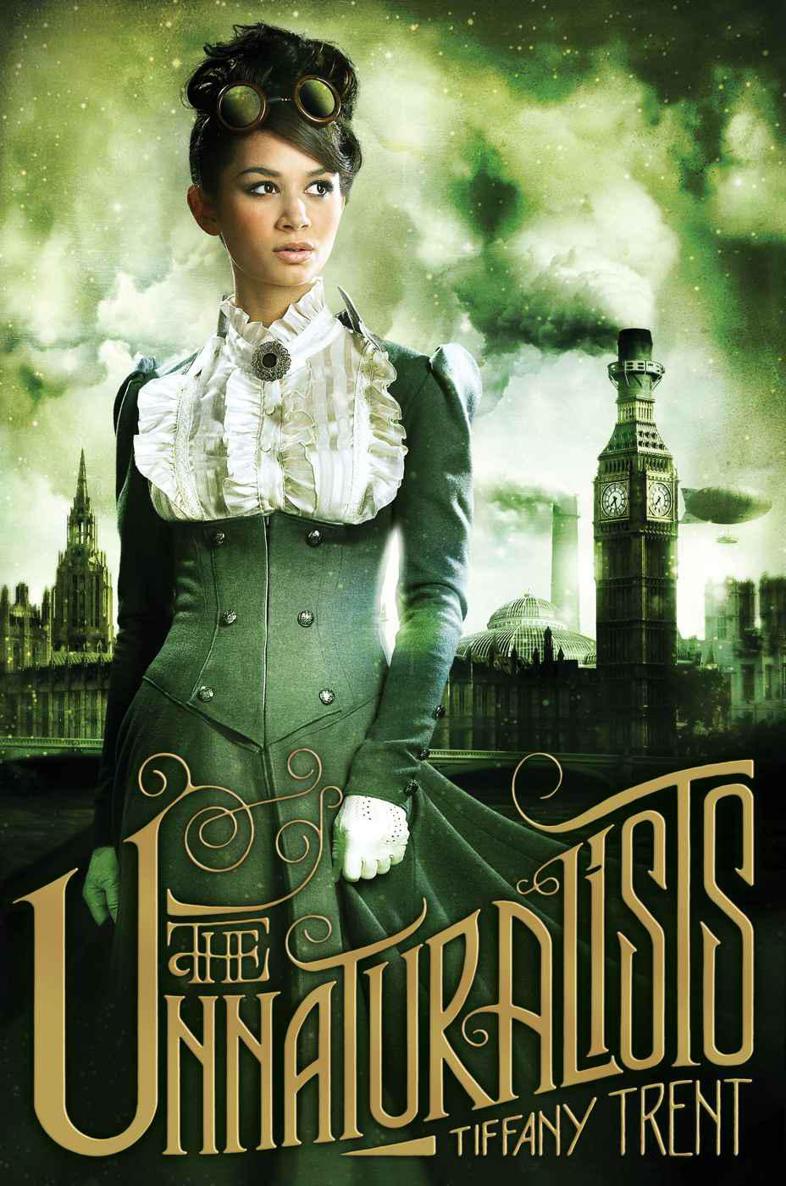

The Unnaturalists

Authors: Tiffany Trent

Contents

To Tricia Scott, the Queen of Art

“As the voice of Science increases in strength, the horns of Elfland blow ever fainter and fainter. . . .”

—E

LIZABETH

R

OBINS

P

ENNELL

T

he Sphinx stares at me from her plinth. I edge closer, daring her to open her mouth and enspell me with her riddles. She crouches, eyes a-glitter, teeth gleaming through parted lips.

But she never moves.

She can’t, trapped as she is by the paralytic field that holds her suspended. Once, the Museum of Unnatural History stuffed specimens of the Greater Unnaturals instead of presenting them like this. There are a few of them still in odd corners of the Museum, but they never fare well. Most have crumbled into dust. Decades ago, the paralytic field was developed by a Pedant working for the Raven Guard, and we use it to hold the larger specimens we otherwise couldn’t. Only the Lesser Unnaturals—sylphids and the like—are stuffed and mounted now, and I do most of that work.

Which means, basically, that the Sphinx crouching just beyond the pulsing blue light is alive, even if she can’t move. I’m certain she would eat me if she could.

I like leaning in toward the field, tempting her, tempting Fate. (Though the saints know a devotee of the Church of Science and Technology should not even think of temptations or Fate). I like the way the etheric energy buzzes and tingles just at the edge of my skin.

A patron—some dowdy woman with a whimpering babe in a perambulator—makes disapproving noises. I lean closer to the field, so close the energy leaks into my nose and the corners of my eyes. I look over at the woman and grin while my hair crackles.

We used to do this with the little kobold on display at Miss Marmalade’s Seminary for Young Ladies of Quality. None of the other girls thought anything of it, until I told Effie Lindler how to trip the field.

I didn’t think she’d do it, of course! But when she did, it was quite possibly the best day of all my sixteen years.

The kobold wreaked havoc, cursing Miss Marmalade with the Malodorous Slime and turning Effie into a cow. For some reason, he left me unharmed, even giving me a slight nod as he leaped from the dance hall window. I don’t know if the kobold was ever caught, but the upshot was that Father and some junior Pedants were called in to clean up the mess, I was expelled, and I’ve been here in the Museum working for Father ever since.

That was almost a year ago. I’m very nearly seventeen now, and those days of fun are over. Besides, this field is much stronger than that at Miss Marmalade’s. One would have to be as powerful as a witch or warlock to trip it, much less survive trying. Since all magic (except that sanctioned by the Empress) is heresy, there’s nothing to worry about there.

But I can’t resist teasing this woman just a bit more. I spread my arms as if hugging the wall of energy to me. She gasps. The needling oddness hovers at my fingertips.

Then, the unthinkable happens.

Someone pushes me hard in the back and I pitch forward.

The woman’s scream follows me through the pulsing curtain.

The etheric energy zips across my eyelids, my wrists, slithering down my stockings into my boots. I am suspended in the crackling field for several seconds before my palms and knees hit the floor.

I breathe slowly, afraid I’m nothing more than a cinder. But cinders don’t breathe. Nor do they think. It’s impossible, though, that I’m still alive. I should be burned to a crisp.

The field is down. Somehow, I’ve tripped it, though that, too, should be impossible.

The Sphinx’s claws splay before me, five perfectly curved scimitars. One lifts and ticks against the marble plinth as the beast stretches her toes.

I may not be alive for long. Lucky for the screaming woman that she’s managed to faint dead away.

I probably should recite Saint Darwin’s Litany of Evolution now, but the words of my patron saint escape me. Something about all of us being tiny twigs on one small branch on the Tree of Life, et cetera, et cetera. I can’t remember. Terror dissolves whatever words lurk on my tongue.

I hear a sound, as of a thousand buzzing bees. The sound might almost make words, except that I know Unnaturals cannot truly talk. Oh, there are stories, of course—the Riddle of the Sphinx, for example—but it’s been definitively proven by our Scientists and Pedants that Unnaturals are dumb, irrational creatures. Like dogs or horses, only perhaps a bit more cunning and certainly more deadly. Because they have magic.

“Be still!” someone shouts through the sudden silence.

I’m trying to place the owner of the voice—someone male and educated. And youthful.

“And do not look into her eyes,” he says, coming closer.

I search my memory as to why I shouldn’t look into the face of the Sphinx—isn’t it the Basilisk one is supposed to avoid?—but that information is as inaccessible as the Litany. So I don’t look up. I look aside at the owner of the voice instead. He wears the teaching robes of a Pedant, though he isn’t wearing a wig. He’s so young that I check to make sure he isn’t wearing Scholar robes. But no. He has the braid on the collar and the long, colorful tassels, even if his garment looks a bit ragged.

He isn’t particularly handsome. Something about his face looks wrong, but I can’t tell if that’s because I’ve been nearly blinded by falling through the field or . . . It’s as though he’s blurred at the edges. I blink, trying to place his shifting features as he signals to two Scholars to remove the petrified woman and her babe. I know every Pedant here, but I have no idea who he is.

He crouches at the burn line that used to be the edge of the field. He holds out a hand, his easy smile betrayed by the concern in his eyes. For one second, I think I see his face clearly, like sun breaking through cloud, but then he speaks.

“Come to me slowly.”

I focus on his eyes, blue beyond all Logic. I am terribly annoyed that I’ve even noticed the color of his eyes. I turn from him, trying to stand on my own. The Sphinx’s gaze catches mine. And then I’m frozen, unable to feel my cramped toes in my too-small boots anymore.

The buzzing grows louder, almost intolerable. The Sphinx is so close I can smell her breath—metallic and dry as an iron desert.

The Pedant whispers something I can’t hear, pulling me by the wrist and thrusting me behind him. He steps between me and the

Sphinx, breaking her hold. The buzzing seems to migrate from my ears into my limbs.

The Sphinx turns, intent on this Pedant who has placed himself literally in the jaws of Death to save me.

I take two more trembling steps backward, but I can’t look away from the Sphinx and the new Pedant. A strange glow, like the faintest of fields, dances across the man’s fingertips. All sound drains away. It’s as though we three are indelibly etched on the air of the hall—girl, man, and monster—and everything around us has faded into ghosts and shadows. The Pedant retreats slowly so that the burn line is between his scuffed boots and the Sphinx’s claws.

“Raise the field!” someone cries. The silence shatters and there’s movement in the alcove where the rusty field box hangs. The switch is thrown and the blue wall rises between the Pedant and the Sphinx, trapping the Unnatural again just before she can leap.

The young Pedant approaches me, and I try to stop gaping, to breathe through my nose again. The crowd surges closer, except for the woman I teased who pushes her baby out of the Grand Hall as quickly as possible. I’m acutely aware that I’m not wearing gloves, that my laboratory apron is stained, and that my hair is probably a sizzling halo around my head from contact with the paralytic field.

“My apologies, miss, for my rough treatment,” the Pedant says. There’s a glint of humor in his eyes that I mislike. “Do you require further assistance?”

I draw myself up and look him fully in the face. “I thank you, sir, for aiding me”—I cannot bear to use the word “rescue”—“but I require nothing further at present.”

There are gasps from the crowd. I suppose I’ve insulted him, but

there’s something about his manner that’s far too familiar for my liking. Much as Aunt Minta and Father might want me to think differently, I prefer the life of a Scientist, working here at the Museum with Father. It is my most cherished, most secret dream to be the first female Pedant—well, the first in several generations—and no man will overshadow that.