The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst (67 page)

Read The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst Online

Authors: Kenneth Whyte

BOOK: The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst

13.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

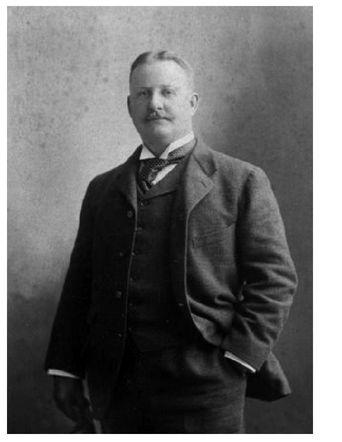

Frederic Remington.

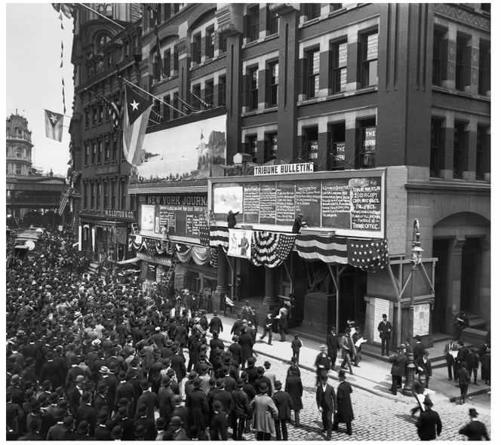

Cuban and American flags, and headline bulletins outside the

Journal

and

Tribune

offices.

Journal

and

Tribune

offices.

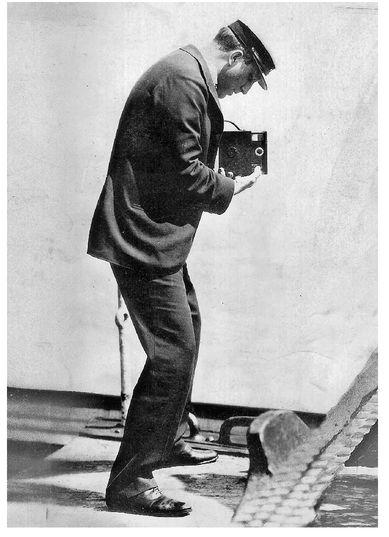

W.R. on deck, off the coast of Cuba, covering the Spanish-American War.

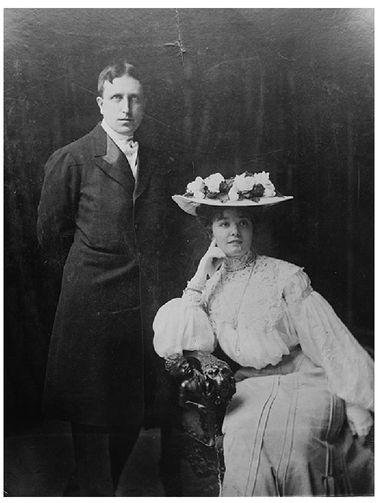

The only published wedding photo of Mr. and Mrs. W.R. Hearst.

William Randolph Hearst as he is most often remembered.

It seems a ridiculous idea, government by newspaper, but it ’s important to be precise about what Stead had in mind. He was not proposing a coup d’état. He was not suggesting editors assume direct authority for the public business. Rather, he wanted them to use their resources and their command of public opinion to raise and debate issues, and to rally both the people and their governments toward solutions. Stead had only contempt for journalists who treated newspapers as mere money machines or who argued that leadership, guidance, and governance were beyond the ambit of their craft. He called them eunuchs. The future, Stead declared, would belong to the journalist who possessed the instinct and capacity for government and who was bold enough to accept the challenge. He would be limited only by the scope of his knowledge and faculties and by the extent of his circulation.

Of all the editors then working in Europe and North America, Stead held that none was more likely to rise to the position of “uncrowned king of an educated democracy” than William Randolph Hearst. Much of Stead’s chapter on government by journalism is devoted to Hearst, “the most promising journalist whom I have yet come across. He has education, youth, energy, aptitude, wealth, and that instinctive journalistic sense which is akin to genius.” Stead applauded Hearst for choosing his staff “wisely and well,” and for not being afraid to pay top dollar for top talent. But he fixes praise for the

Journal

’s success firmly on Hearst himself: “No one did more to give the newspaper character and success than the young millionaire, who was to be seen in his shirt-sleeves through the hottest nights in the sultry summer toiling away at proofs and forms until the early hours when he saw his paper to press. Members of his staff who worked like niggers could not complain when they saw their chief working harder than any of his salaried employees.”

49

Journal

’s success firmly on Hearst himself: “No one did more to give the newspaper character and success than the young millionaire, who was to be seen in his shirt-sleeves through the hottest nights in the sultry summer toiling away at proofs and forms until the early hours when he saw his paper to press. Members of his staff who worked like niggers could not complain when they saw their chief working harder than any of his salaried employees.”

49

Stead was struck, as were others, with the discrepancy between Hearst’s personal modesty and his newspaper’s style. He describes the

Journal

as “Broadway in print—Broadway at high noon, with cars swinging backward and forward along the tracks, and the myriad multitudes streaming this way and that, life everywhere.” He claims that the direction or governing purpose of the paper was not always discernable amid the fever and sensation but that it finally found expression in the slogan “While Others Talk the

Journal

Acts.” He ends the chapter by begging Hearst to realize the possibilities of his position and embrace a supreme ambition, such as making New York the most humane and habitable city in the world. “Certainly no man in all New York,” Stead concludes, “has such a chance of combining all the elements that make for righteousness and progress in the city as the young Californian.”

50

Journal

as “Broadway in print—Broadway at high noon, with cars swinging backward and forward along the tracks, and the myriad multitudes streaming this way and that, life everywhere.” He claims that the direction or governing purpose of the paper was not always discernable amid the fever and sensation but that it finally found expression in the slogan “While Others Talk the

Journal

Acts.” He ends the chapter by begging Hearst to realize the possibilities of his position and embrace a supreme ambition, such as making New York the most humane and habitable city in the world. “Certainly no man in all New York,” Stead concludes, “has such a chance of combining all the elements that make for righteousness and progress in the city as the young Californian.”

50

If there was ever a moment when editors could plausibly aspire to fill the role Stead imagined for them, it was here in the waning days of the nineteenth century. The contemporary view that the yellow press existed on “the level of the

National Enquirer

and other supermarket tabloids” is wildly off target.

51

Far from being shady, squalid, or trivial, the yellows were big, rich businesses run out of towering buildings with elevators, telephones, and electric lights. There seemed no limit to their potential size and reach. Their dazzling color presses could spit out a million copies a day for delivery over thousands of square miles. They could generate a fresh edition with the latest news from a conflict halfway around the globe in a matter of minutes. They were staffed with college graduates and first-rank journalistic talent—men of high purpose and powerful expression who daily held the attention of larger audiences than most candidates for the presidency would address in an entire national campaign. They spoke to the nation with a frankness and familiarity that politicians could only envy.

National Enquirer

and other supermarket tabloids” is wildly off target.

51

Far from being shady, squalid, or trivial, the yellows were big, rich businesses run out of towering buildings with elevators, telephones, and electric lights. There seemed no limit to their potential size and reach. Their dazzling color presses could spit out a million copies a day for delivery over thousands of square miles. They could generate a fresh edition with the latest news from a conflict halfway around the globe in a matter of minutes. They were staffed with college graduates and first-rank journalistic talent—men of high purpose and powerful expression who daily held the attention of larger audiences than most candidates for the presidency would address in an entire national campaign. They spoke to the nation with a frankness and familiarity that politicians could only envy.

The very size of their circulations lent Hearst and Pulitzer authority. Huge sales were a sign of broad public favor, which in itself was political currency. The primacy of public opinion was still a “vital unifying tenet” in the operations of U.S. governments at all levels in the nineteenth century, writes historian Gerald F. Linderman. “Americans assumed a priori both the existence of public opinion and its accurate and automatic translation into political decisions.”

52

Newspapers, in such a world, were crucial intermediaries. Politicians used the press to monitor the attitudes and temper of electors; in the absence of broadcast, broadband, and organized polling, there were few other ways to keep up. They also responded to issues and campaigns in the dailies, and deferred to them to an extent today’s politician would consider humiliating. They did so out of regard for the public voice: “conciliating the priest in worshipping the deity,” as one historian puts it.

53

Hearst and Pulitzer, to extend the analogy, had by far the largest parishes, and these were growing at intimidating rates.

52

Newspapers, in such a world, were crucial intermediaries. Politicians used the press to monitor the attitudes and temper of electors; in the absence of broadcast, broadband, and organized polling, there were few other ways to keep up. They also responded to issues and campaigns in the dailies, and deferred to them to an extent today’s politician would consider humiliating. They did so out of regard for the public voice: “conciliating the priest in worshipping the deity,” as one historian puts it.

53

Hearst and Pulitzer, to extend the analogy, had by far the largest parishes, and these were growing at intimidating rates.

Politicians could not afford to ignore the yellow press. Pulitzer had helped to bully Grover Cleveland into dropping his bond sale. Hearst had played as important a role in a national election as any newspaper in U.S. history. Congressmen, senators, and governors responded in impressive numbers to opinion surveys undertaken by the

Journal

and the

World.

When Sylvester Scovel was arrested, the Senate requested that the secretary of state intervene with Spain for his protection. The request was granted. A sizable party of congressmen and senators, including a member of the House Committee on Naval Affairs and a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee, accepted Hearst’s invitation to join his newspaper’s fact-finding tour of Cuba; when they returned, they vouched for the accuracy of their host’s journalism. McKinley not only felt it advisable to meet Evangelina Cisneros in Washington after she had been illegally liberated from a Spanish jail, but also complimented the

Journal

on its enterprise.

Journal

and the

World.

When Sylvester Scovel was arrested, the Senate requested that the secretary of state intervene with Spain for his protection. The request was granted. A sizable party of congressmen and senators, including a member of the House Committee on Naval Affairs and a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee, accepted Hearst’s invitation to join his newspaper’s fact-finding tour of Cuba; when they returned, they vouched for the accuracy of their host’s journalism. McKinley not only felt it advisable to meet Evangelina Cisneros in Washington after she had been illegally liberated from a Spanish jail, but also complimented the

Journal

on its enterprise.

Better evidence of how politicians were affected by what they read in the yellow press comes from Marcus Wilkerson’s 1932 study of public opinion during the Cuban crisis. “Senators and representatives, seemingly moved by the atrocity stories found in the press, made stirring speeches in favor of Cuban belligerency, using portions of the news reports from Cuba. . . . The number of resolutions introduced in Congress dealing with Cuba and the speeches resulting from the introduction of such measures increased with the number of atrocity stories carried by the press.” From late 1896 through the first half of 1897, the period in which atrocity stories were most plentiful, with Hearst and Pulitzer leading the way, twenty-five separate resolutions dealing with Cuba were introduced in Congress.

54

54

The notion of the press filling a perceived political vacuum was far less ludicrous than we might assume today, writes Linderman.

55

So too was the prospect of Hearst as the uncrowned king of an educated democracy, operating in a whole new realm outside of governmental authority, beholden to none but his readers, with his newspapers and his influence still expanding. Early in 1898, the start of his third year in New York, Hearst bought the cream of Dana’s collection of pottery and paintings at an estate auction, and his publishing rivals continued to worry.

56

55

So too was the prospect of Hearst as the uncrowned king of an educated democracy, operating in a whole new realm outside of governmental authority, beholden to none but his readers, with his newspapers and his influence still expanding. Early in 1898, the start of his third year in New York, Hearst bought the cream of Dana’s collection of pottery and paintings at an estate auction, and his publishing rivals continued to worry.

56

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Suddenly the Dinnerware Began to Vibrate

A

t the beginning of 1898, Hearst was more impatient than ever for a resolution of the Cuban crisis, and he was not alone. Spain JL and the rebels were locked in a stalemate. Credible accounts of Spanish atrocities against noncombatants continued to surface in the press, as did horrific reports of human suffering in reconcentration camps. The

Journal,

the

World,

the

Sun,

and other pro-Cuban papers kept urging the McKinley administration to fulfill its duties as steward of the Western Hemisphere and compel Spain to bring peace to its possession. Most members of Congress and, in all probability, a majority of the American people concurred, but the president, while not insensitive to the clamor for action, was determined to avoid any measures that might lead to a military confrontation. He had seen enough bloodshed in the Civil War, and was determined to use patient diplomacy and “every agency of peace” to negotiate a settlement mutually satisfactory to Spain, Cuba, and the United States.

1

He offered Madrid his friendly offices in coming to terms with the rebels and he suggested that Washington might be forced to act in the name of humanity and U.S. interests if Spain could not arrange a settlement, but he mentioned intervention as a remote and unpleasant specter, not as an imminent threat.

t the beginning of 1898, Hearst was more impatient than ever for a resolution of the Cuban crisis, and he was not alone. Spain JL and the rebels were locked in a stalemate. Credible accounts of Spanish atrocities against noncombatants continued to surface in the press, as did horrific reports of human suffering in reconcentration camps. The

Journal,

the

World,

the

Sun,

and other pro-Cuban papers kept urging the McKinley administration to fulfill its duties as steward of the Western Hemisphere and compel Spain to bring peace to its possession. Most members of Congress and, in all probability, a majority of the American people concurred, but the president, while not insensitive to the clamor for action, was determined to avoid any measures that might lead to a military confrontation. He had seen enough bloodshed in the Civil War, and was determined to use patient diplomacy and “every agency of peace” to negotiate a settlement mutually satisfactory to Spain, Cuba, and the United States.

1

He offered Madrid his friendly offices in coming to terms with the rebels and he suggested that Washington might be forced to act in the name of humanity and U.S. interests if Spain could not arrange a settlement, but he mentioned intervention as a remote and unpleasant specter, not as an imminent threat.

Other books

Rules of Civility by Amor Towles

Some Kind of Normal by Juliana Stone

NO Quarter by Robert Asprin

Shotgun Groom by Ruth Ann Nordin

They Call Me Baba Booey by Gary Dell'Abate

Dangerously Hers by A.M. Griffin

Beachcombing at Miramar by Richard Bode

Pale Rider: Zombies versus Dinosaurs by James Livingood

The Mezzo Wore Mink by Schweizer, Mark

Blood and Fire by Ally Shields