The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst (34 page)

Read The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst Online

Authors: Kenneth Whyte

BOOK: The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst

5.18Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

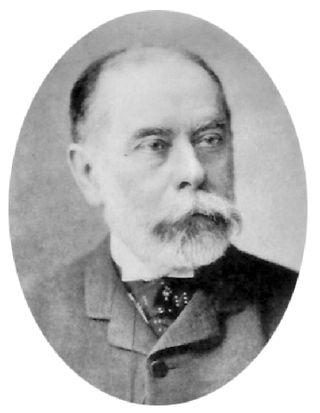

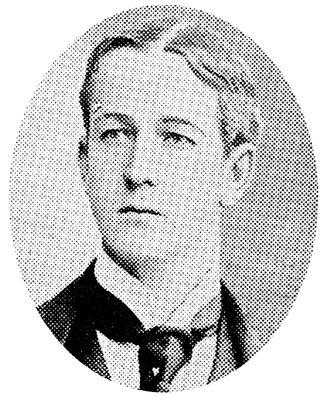

The aristocratic Republican, Whitelaw Reid.

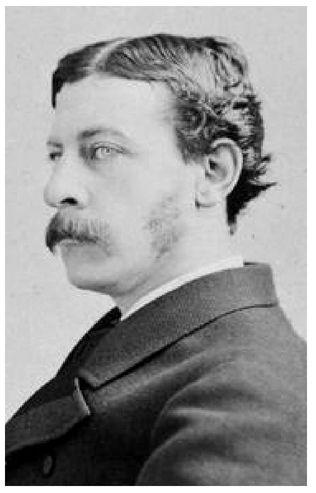

The precociously dissolute James Gordon Bennett.

The brilliant misanthrope, Edwin Godkin.

The shrewd whelp, Adolph Ochs.

The

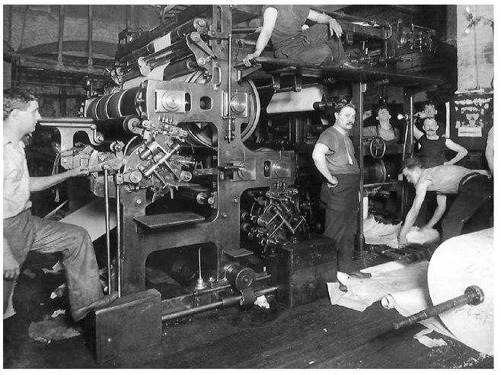

Journal

’s magnificent pressworks: as many as forty editions a day.

Journal

’s magnificent pressworks: as many as forty editions a day.

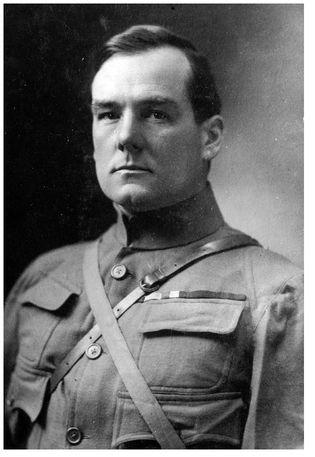

Richard Harding Davis, posing as a war correspondant.

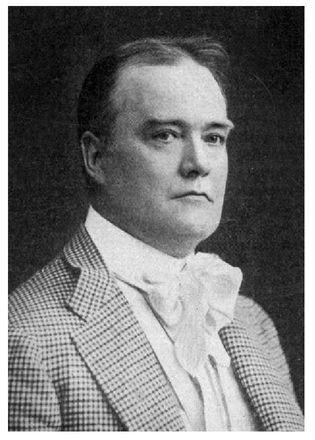

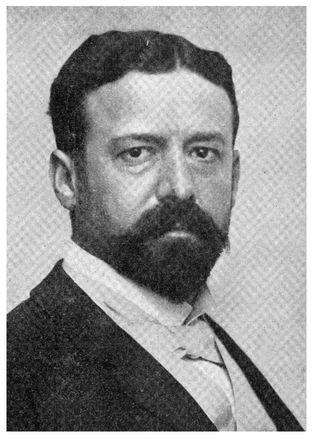

Arthur Brisbane, who cherished his superf iciality.

Alfred Henry Lewis: a singularly vicious hater.

James Creelman: profane, invasive, fearless.

Millicent Willson (left) with sister, Anita, and mother, Hannah: at first it wasn’t clear which girl interested Hearst.

THE MOST DIRECT AND DETERMINED of the

Journal

’s assailants in the last weeks of the campaign was Joseph Pulitzer. Whatever the state of his health, few things engaged the

World

publisher like a presidential contest. His one-time colleague and biographer Donald Seitz reports that he spent the whole election season “in unceasing labor, never for a waking moment out of touch with the telegraph. . . . The fever of the fight revived his bodily strength and he labored as few in the fullness of their powers could do, sustained by his devotion to the right.” Pulitzer bombarded his editors with orders, ideas, information, and criticisms. He personally supervised his star reporter, Creelman. Yet despite his efforts, the

World

wasn’t enjoying the campaign.

47

Journal

’s assailants in the last weeks of the campaign was Joseph Pulitzer. Whatever the state of his health, few things engaged the

World

publisher like a presidential contest. His one-time colleague and biographer Donald Seitz reports that he spent the whole election season “in unceasing labor, never for a waking moment out of touch with the telegraph. . . . The fever of the fight revived his bodily strength and he labored as few in the fullness of their powers could do, sustained by his devotion to the right.” Pulitzer bombarded his editors with orders, ideas, information, and criticisms. He personally supervised his star reporter, Creelman. Yet despite his efforts, the

World

wasn’t enjoying the campaign.

47

There was, for starters, Pulitzer’s throbbing indignation at the Democrats’ rejection of his counsel on the currency question. That Bryan and his outrageous platform were finding an audience didn’t sit well with him either. Pulitzer had made his fortune as an evangelist for democratic ideals, but the ’96 campaign was shaking his faith in the intelligence and morality of the people and in the viability of the Republic. Worse, he had nowhere to turn. Despite his preference for the gold standard, Pulitzer couldn’t bring himself to support the Republicans. His editorial page was still scorching McKinley for his reluctance to support anti-trust legislation and to speak against combinations of capital and private monopolies. In the end, the best the

World

could say of McKinley was that he wasn’t Bryan. Pulitzer was thus without a horse in a big derby. For an old campaigner, it was a kind of death.

World

could say of McKinley was that he wasn’t Bryan. Pulitzer was thus without a horse in a big derby. For an old campaigner, it was a kind of death.

And then there was Hearst, making a reputation for himself in a role traditionally reserved for Pulitzer. Hearst was the champion of the Democratic ticket and of the Democratic platform, rushing to press each day with a righteous sense of purpose. Pulitzer was certain the Democrats were headed for defeat and that Hearst’s bubble would burst along with Bryan’s, but he did not like for a moment being eclipsed by an upstart. Especially an impudent upstart. In addition to splashing on his front-page Pulitzer’s memo to news agents, Hearst had confirmed in late August that he was planning to launch an evening edition to take on the

Evening World.

Evening World.

The

Evening Journal

made its debut on September 28, 1896, with five weeks remaining in the campaign. That same say, the morning

Journal

published on its front page the news that its circulation had passed the 400,000 mark, and a letter to Hearst from the president of the printing-press giant R. Hoe & Co. (which also built Pulitzer’s plant), acknowledging receipt of yet another order to upgrade the

Journal

’s printing capacity:

Evening Journal

made its debut on September 28, 1896, with five weeks remaining in the campaign. That same say, the morning

Journal

published on its front page the news that its circulation had passed the 400,000 mark, and a letter to Hearst from the president of the printing-press giant R. Hoe & Co. (which also built Pulitzer’s plant), acknowledging receipt of yet another order to upgrade the

Journal

’s printing capacity:

You may not be aware of the fact, but the orders received from you during the past year embrace a larger number of machines, with a greater producing capacity, than we have furnished to any one customer during a similar period of time. Your circulation having, since we received your first order, on October 1st, 1895, increased from fifty thousand (50,000) to four hundred thousand (400,000) daily, we think we have reason to congratulate ourselves upon being able, with the machines already furnished, to so nearly keep up with your requirements.

48

Pulitzer was not one to take all this lying down. The advent of the

Evening Journal

infuriated him. While less prestigious journalistically than their morning cousins, evening papers raked in advertising on the assumption that consumers were more likely to make their purchases at the end of a workday than at the beginning. The

Evening World,

sharing costs with the morning

World,

was probably the most profitable daily in town. Now both

Worlds

were under attack—actually, all three, counting Sunday. In his rage, Pulitzer grasped at a story he believed would all at once expose the folly of the Democrats, return the

World

to its rightful place at center stage in the election campaign, and destroy the interloper, Hearst.

Evening Journal

infuriated him. While less prestigious journalistically than their morning cousins, evening papers raked in advertising on the assumption that consumers were more likely to make their purchases at the end of a workday than at the beginning. The

Evening World,

sharing costs with the morning

World,

was probably the most profitable daily in town. Now both

Worlds

were under attack—actually, all three, counting Sunday. In his rage, Pulitzer grasped at a story he believed would all at once expose the folly of the Democrats, return the

World

to its rightful place at center stage in the election campaign, and destroy the interloper, Hearst.

Other books

Bride by the Book (Crimson Romance) by Kathryn Brocato

In the Field of Grace by Tessa Afshar

Namaste by Sean Platt, Johnny B. Truant, Realm, Sands

The Noble Outlaw by Bernard Knight

Supersymmetry by David Walton

Her Heart's Secret Wish by Juliana Haygert

Wild Lust (BBW Paranormal Shifter Romance Bundle) by Kay, Mindy

Patrimony by Alan Dean Foster

Damned for Eternity by Jerrice Owens

The Stricken Field by Dave Duncan