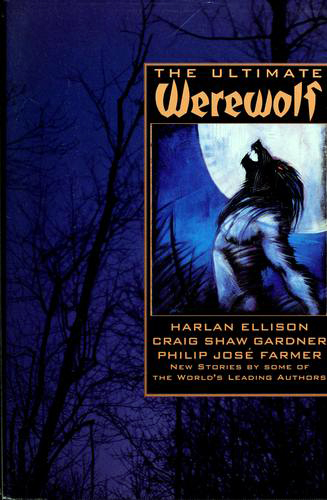

The Ultimate Werewolf

Read The Ultimate Werewolf Online

Authors: Byron Preiss (ed)

Tags: #anthology, #fantasy, #horror, #shape-shifters

▼▼▼

That

was one helluva year,

1941.

Life on this planet was savagely altered for all time, for every human being, in ways too obscure and too terrible to predict. We began to metamorphose—to change shape and purpose—to become beasts of a different kind than had ever roamed the Earth before.

Looking in the mirror will not reveal the face of the creature. We look about the same. But that's only because the full moon isn't shining. Try the mirrors of television, advertising, newspaper reports, crime statistics; or look out your window at the color of the sky, the litter in the street, the graffiti on the wall. It started in earnest in 1941.

In that year, powerful influences were hardwired into our society. We went to war in the most massive assemblage of force and brutality since 1237 and the beginning of the Mongol conquest of most of the civilized world. 1941 was the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, the full-bore entry of America into World War II, the proclamation on my eighth birthday— May 27th—by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt of a state of national emergency; it was the year the human race poured fuel-oil on the conflagration and four years later added to the flames with the power of the split atom.

And the world of fantasy literature was changed forever in that year. But no one seemed to notice.

In 1941 movies were at the height of their mesmeric power over the American public. We were coming out of the Depression, millions were still on the road, selling pencils, working for what they called "coolie wages"—and radio, pulp magazines, and movies were the only inexpensive diversions. Despite the false courage embodied in Shirley Temple songs and Busby Berkeley kick-turn-kick-turn assurances that

We're in

the Money,

scrounging up a dime for a Saturday matinee double-bill was no less than hardscrabble for most Americans.

But, oh, what a pull on every one of us; to be drawn into those gorgeous palaces of dreams. 1941 was arguably the best year for cinema before and since. In that twelvemonth before the world pitched headlong into darkness, here is a

partial

list of the more than four hundred motion pictures produced by Hollywood:

The Maltese Falcon

Citizen Kane

Dumbo

Sergeant York

Major Barbara

How Green Was My Valley

The Lady Eve

Here Comes Mr. Jordan

The Stars Look Down

Suspicion

The Little Foxes

Meet John Doe

Ball of Fire

Leonard Maltin gives four stars to seven of those, and three and a half to the remaining six. What a lineup! Films so influential that even today, when critics are polled, at least three off that list perennially find placement among the top ten of all time. But there was one more, that went unnoticed, that altered the world of fantastic literature as surely and positively as Hitler altered the world at large sorely and negatively. Was it the John Lee Mahin-scripted, Victor Fleming-directed version of Robert Louis Stevenson's classic

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,

starring Spencer Tracy, Ingrid Bergman, Lana Turner, and Sir C. Aubrey Smith

...

a film on which hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent for a lavish production by MGM, the most prestigious studio of its day? In fact, no.

It was a minor, only-passingly-noted, "B" (for

bottom)

second feature on a double-bill. It was from a studio hardly known as the House of Influential Cinema. It was made on a parsimonious budget; and though it boasted such outstanding thespic talents as Claude Rains, Ralph Bellamy, Warren William, and Bela Lugosi (in a cameo role), it was by no means a

big

film, or even a film that Universal pushed very hard. It was intended to come, and to go; to make a few bucks, and to fill the hole in a Saturday matinee that came immediately after a Charles Starrett "Durango Kid" western.

It has been fifty years since that intentionally disposable chunk of celluloid trash was tossed out onto the movie screens of America, like an unwanted infant wrapped in newspaper and flung into a dumpster. And if you check any exhaustive reference on the Oscars (such as ACADEMY AWARDS:

The Ungar Reference Index)

you will discover that in no category did that film get a nomination.

Yet fifty years later, even with the plethora of period films committed to videocassette, aired late night on local channels, run and rerun on cable—even specialty channels such as American Film Classics—and screened in the dwindling number of revival theaters or in film schools or museum cinema programs, you will likely never see

Dive Bomber,

Aloma of the South Seas, Son of Monte Cristo, or Las Vegas Nights . . .

all of which received Oscar nominations in one or another category.

But I'll bet you an eyeball that somewhere in these here great Yew- nited States, today, tonight, tomorrow, an enraptured audience is watching Lon Chaney, Jr., as

The Wolf Man.

A film created as a throw- away fifty years ago, exquisitely scripted by Curt Siodmak, directed by George Waggner, moodily art directed in the horrorstory equivalent of

film noir;

a film that forever cast into the American idiom the timeless words of Madame Maria Ouspenskaya:

"Even the man who is pure in heart

"And says his prayers by night

"May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms

"And the moon is pure and bright."

Before the seventy-one minutes of

The Wolf Man

were unleashed on generations of kids whose spines creaked and whose hair trembled as they watched tragic Lawrence Talbot metamorphose into a blood-hungry beast thing, the werewolf was barely considered fit fodder for fantasy. Yes, there had been a 1913 silent,

The Werewolf

two or three French films featuring lycanthropy, and the excellent

Werewolf of London

with Henry Hull in 1935, but that was just about the totality. The potboiler picture no one thought would last more than a couple of weeks, has not only endured, it has skewed imaginative literature in its own image for half a century. More than any previous rendition of the werewolf mythos,

The Wolf Man

created an entire genre.

Purposely, I'll not rehash the litany of the werewolf theme in classical literature: Dumas

-pere's

the wolf leader

in 1857, Captain Marryat's "The White Wolf of the Hartz Mountains" in 1839, or even the first known introduction of the werewolf antetype in English fiction—the 13th century court romance by Marie de France, "Lay of the Bis- clavaret." Nor will I dwell at length on images of the werewolf in phe- nomenological anecdote . . . though it wouldn't hurt you to look up Freud's

Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis

(1909) in which the father of modern psychoanalysis treats the case of a wealthy young Russian whose history is now commonly referred to as being that of the "Wolf Man."

Those who want irrefutable documentation of the longevity, fecundity, and legitimacy of the werewolf motif in literature are commended to three excellent essays: "Images of the Werewolf" and "The Werewolf Theme in Weird Fiction," both by Brian J. Frost, each exhaustive and breathtakingly lucid, and both available in Frost's frequently-reprinted 1973 paperback anthology,

book of the werewolf

(Sphere Books Ltd.); and Bill Pronzini's 1978 essay on the form in his anthology

werewolf!

I choose to sidestep Sabine Baring-Gould and Guy Endore (who was a terrific gentleman, whom I was privileged to know) and Montague Summers, to suggest that for all its weighty and unchallengeable credentials, the man-into-wolf story never really came into its own until Lon Chaney, Jr. assayed the role of Curt Siodmak's Lawrence Talbot and . . .