The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode (17 page)

Read The Tunnel of Hugsy Goode Online

Authors: Eleanor Estes

"Draw my name on my forehead, Tornid," I said. "In case I get lost, you can spot me. My name 'Copin' will shine in the dark like neon lights on Times Square."

He did this. "Stop wrinkling your forehead," he said. "C O P I N." He spelled it as he went.

Then I wrote T O R N ID on his forehead. We both shone in the dark now like the words written on the wall did. We zigzagged our lights across our faces, and our names seemed to wiggle on our foreheads, seemed to dangle in the tunnel darkness as though not connected to us. We turned our lights off, and all Tornid could see of me was my name, and all I could see of him was his name. It was eerie.

'"Better than string, eh, Tornid, old boy, old boy?" I said.

"More up-to-date," he said again.

"This is a modern journey in a modern maze, not an ancient one like Theseus had to find the Minotaur in," I said.

Then I drew a scary face on the wall. It shone. Whoever invented this chalk invented a neat thing. I wrote our names on the wall, too, and the date. "They may come and find us in a hundred years, if we get lost," I said. "Kids digging in the ruins may find us. Bones then, just bones, and end up in a museum with a label ... Brooklyn

Puer sapiens. Puer

means 'boy,'

sapiens

means 'wise,'" I explained.

"Spanish?" he said. "Poor sap?"

"No," I said. "Latin. I learned it from Star."

We went on. "Copin," said Tornid. "Where are the skeletons? Not the poor sap type, the real type."

"Oh, we'll get to them," I said. "Don't you worry. And it's pu-er sap-i-ens, not 'poor sap,' lug."

I turned around. We could just barely see the Throne of King Hugsy the Goode from here, just a blur of the name over it. We should have written it in larger letters. I couldn't get that chair out of my mind. There it was. Every time you looked at it you thought someone, some guy invisible or not, some phantom, might be sitting in it and studying us as we went on into the glooming ... just two small Brooklyn boys ... one age eleven and the other eight on a historic journey.

I said, "Tornid, the skeletons are probably in the large pit under Jane Ives's house, a really central spot, according to my map. Those skeletons may have been there all of our lives, Connie's life, too, and would be there until doomsday if that boy, Hugsy Goode, had not said there probably was a tunnel under the Alley. It's too bad he's grown up and moved away and gone to college. I know he'd like to know he was on the right track when he said those words ... be part of this expedition."

"Yeah ... I know," said Tornid. His voice was shimmery, like his name on his forehead. And on we went into the glooming.

We must have passed Jane Ives's house by now. We didn't stop to see if there was a crawling or narrow passageway to it from the main stem of the T. First we had to find out if there was a Circle. We went straight on ahead to where it should be, if there was one, under where the Circle on top used to be.

"Tornid," I said. "If it's skeletons you want, you have to look in every direction ... we don't

know

they're lopped all together in the

PIT

under J.I. Don't think you're just going to come upon a skeleton grinning at you and saying, 'I'm here.' You have to look."

"I didn't know skeletons could talk," said Tornid. "Maybe the poor sap type can, but none I ever heard of could talk, not the ones in museums. They never say anything. Grinâthat's allâand I hope that one knows not to talk. Just because he's in a tunnel, not a museum, he might think he can..."

I stopped, stood stock-still. "What's that you said?" I asked.

"I just said," said Tornid, "I hope that one doesn't talk. Maybe you are looking for a better oneâone that will say something."

"What are you talking about, cluck?" I asked.

"I'm talking about that one back there," said Tornid.

"What one? Back where?" I said.

"In that pile of stuff back there," he said.

"I didn't see any pile of stuff," I said.

"I did," said Tornid. "And it looked like a skeleton in it. Maybe he wasn't any good ... no good at all, probably."

"Show me," I said. Suddenly my knees grew weak. Tornid wasn't scared ... too young to be.

Tornid flashed his light to "back there." By cricky! There was a long bone sticking out of the rubble with what looked like a big bone toe on it sticking out, too. The rest of him, if there was any rest of him, was in the rubble ... thank goodness!

"Come on, Tornid," I said. "I'm getting out of here."

I ran down the tunnel, passing the

IN

and

OUT

signs, past the psychedelic face wobbling at me horriblyâI wish't I hadn't drawn itâpast the Throne of King Hugsy the Goode, down the Fabian tunnel to T.N.F. and our rope.

"Wait for me," said Tornid.

I waited. I boosted him up and out and hoisted myself out, too. There we were then in clear air, not heavy dark, dank skeleton-infested tunnel air. "Whew-ee!" I said.

And thusly ended Descent No. 3.

"Why were you so scared?" asked Tornid. "It was only a part of a skeleton, not a whole one with a grin. So, why were you so scared?"

Meanwhile, What Had Been Going On Up Top?

What's so scary about just a piece of skeleton? I didn't know, so I didn't answer Tornid. All I knew was I was shaking. Tornid began to shake, too, because shaking is catching. We wobbled out of the Fabians' gate to resume life with human beings, hostile though they might be, and not live life in a tunnel with skeletons, whole or in pieces.

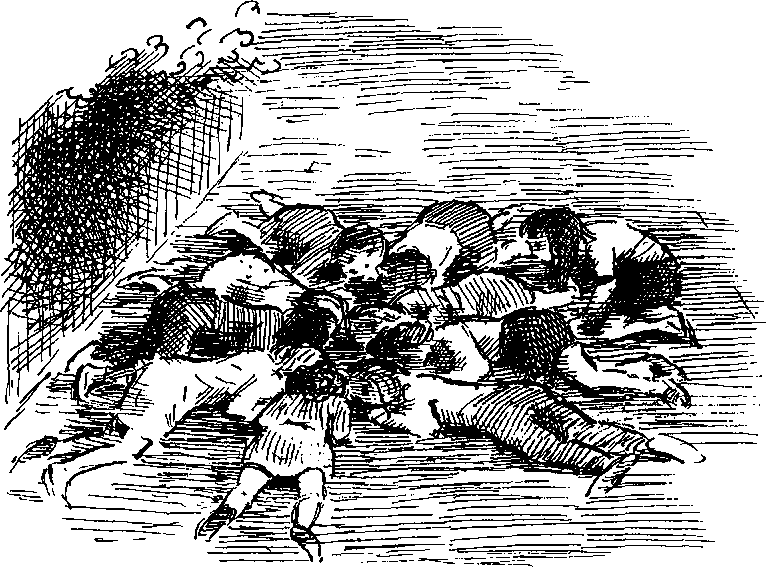

We were not met with any hurrahs because all the kids, about ten of them, lay flat on their stomachs, looking like spokes of a wheel, around the drain which was like the hub. Their heads were as close together as they could get around the drain that carried sounds down into the tunnel and, vice versa, carried sounds up. How ignorant the spokes are! They did not know that, although the drain was just an ordinary drain, it was very close to an under-alley tunnel.

Standing outside Fabians' gate, Tornid and me studied this human wheel a moment. Then I put my fingers to my lips, meaning be silent. Then, unobserved by the drain watchers, we jumped over my fence, over Mrs. Harrington's fence, over Jane Ives's fence, over the Arps' fence, and climbed up the Arps' tree.

Then I bellowed at the spokes, "What's up down there?"

Without relinquishing the spot that each spoke held, they turned their heads toward us like turtles.

We jumped out of the tree, sauntered back down the Alley, hands in our pockets. "What's up?" I said. "You hearing the voice of the boogeyboo?"

They passed around a look that meant, "Play it cool."

Tornid said, "Yeah, what's up?" And he laughed his funny hoarse laugh.

"Or ... down?" I asked. I looked down at the spokes from under my eyeglasses.

Tornid's huge gray eyes were sparkling. "Yeah!" he said. "What's down?"

We had broken our rule not to speak to

grils,

but we had made our secret non-contamination sign and were temporarily safe.

"Oh ... nothing," said black-eyed

gril,

a strand of her long brown hair in her mouth.

Blue-eyed Izzie just sniffed.

"Move over, someone," I said. "What's going on? Some new corny game?"

LLIB saidâhis eyes were round and brown and very seriousâ"We hear voices. We hear words."

"Well, let us in on it," I said.

LLIB said, "They told me it was you. I said, 'No, it's Jimmy Mannikin.' And I was right."

"Oh-ho-ho-ho-ho!" I laughed. "And there we were, Tornid and me, up in the Arps' tree!"

We ran away then. Exit laughing.

"Ha-ha," said Tornid. "We fooled them."

What a success our words from the underground had been! We couldn't stop laughing. Our tunnel terror was over. The skeleton leg that had terrified me seemed funny now, too, and we laughed remembering its big bone toe. But we had to figure out about the skeleton. So we went over to Jane Ives's house, where we do a lot of our figuring.

On the way Tornid said, "You's'pose to tell the police when you come upon a piece of skeleton?"

"Not unless it's a whole one," I said. "Maybe we'll come upon the rest of him, or even forty whole ones like they did down in Brooklyn Heights."

I couldn't help it, I began to get the creeps again thinking about the piece of skeleton. Tornid wasn't at all scared. I'd told him there might be skeletons on the tunnel trip, not to be scared, and he wasn't scared. He thought it was OK for there to be skeletons in a tunnel under an Alley where people live, go about their business, have potlucks, and such, blow their cow-horn blasts, swing, jump rope, have visitorsâall this going on on top of a piece of skeleton. "Anyway, it wasn't like those whole ones that time in the

FUNNY HOUSE

you come upon suddenly," said Tornid. But I didn't know what to think.

"Let's ask Jane Ives," I said. "We should have excavated and found out if there was more to him than the leg and the toe."

"Get that next time under," said Tornid.

Shucks! Jane Ives's back door was locked. We looked through the Alley gate. Yop. The old gray Dodge was gone, so she and John were off somewhere, not just Jane over to Myrtle Avenue to do the shopping stint. The theater maybe ... they like to go to the theater.

So that was the end of telling Jane anything yet, and the secret of the tunnel and the skeleton remained just Tornid's and mine. Just as well. I still wanted to surprise Jane when the whole exploration of the tunnel is completedâknock on her door some afternoon when she was cooking dinner, say, "Jane. Hugsy Goode was right. There

is

a tunnel under the Alley. So far, it's as we drew it on some of the maps." Have her say in total surprise ... drop a spoon, perhaps..."Copin! I wondered where you and Tornid were lately ... no new pictures on the door gallery..." Explain then. Explain the whole neat thing and hold her enthralled. That would stoppeth her in her trackeths and never mind she forgot the Worcestershire sauce for my tomato juice.

We sauntered back to the drain. Life under the Alley was scary. But life on top was tame. The drain watchers and listeners were drifting away, the mystery of the words below still unsolved by them ... just as before, the mystery of the words from on top had been unsolved by Tornid and me. Tornid and me had solved ours, though. Ha-ha! One up on the

grils.

At the drain, just Notesy

gril,

Blue-Eyes, and Black-Eyes were still there. "Whatcha listening for?" I asked. "A conversation between ... uh ... two skeletons?"

Tornid and me laughed vulgarly.

Blue-Eyes said, "Skeletons don't talk. They are silent."

To back her up, Black-Eyes said, "They do not have vocal chords."

We sneered at them.

Then we went back to the hidey hole. "Maybe we should board up the entrance so no one will get suspicious," I said.

"Yeah," said Tornid. "And steal the leg, maybe even the chair of Hugsy Goode ... hey, and maybe even write other things on our wall ... bad words..."

But we didn't block up the hole because of the raccoon. He might want to come out and remind himself of the stars. Anyway, just then the cow horn blew, and I had to go home. "

It

was a long day's night," I said.

"Yeah," he said.

"See ya," I said.

"See ya," he said.

I went home whistling, "It's a long day's night," because that's what it had been like down in the tunnel all right. I whistled softly, though, not to rub my mom the wrong way. I still felt grateful for the neat watch bought with all those stamps.

My mom was in a good mood because she had found garb she liked at Job Lots. What a long time ago that seemed ... yet it was just this morning. "What kind of garb is that?" I asked.

"You'll see," she said. "Bayberry got one, too."

"Looks guru," I said.

"They're abas," she said.

She laughed thinking of the stir she and Bayberry Fabian would create when they paid surprise visits on their friends in the Alley in their abas.

I was in a good mood, too, and washed my hands without being told. What a day ... mark it on the calendar! I did. On the big kitchen calendar I marked T.F. People would think that meant Tornid Fabian. But it meant, "Tunnel Found."

A whiff of what my mom was cooking in the oven made the day just about perfect. Barbecued lamb breast. One good thing you can say about my mom is she is a very good cook, and this dish is a specialty of hers. If your mom has never cooked that, brother, then I'm sorry for you, that's all.

Everyone was in a good mood and no one yelled at anyone. Notesy told the story of the voices that came up out of the drain. But she is not a good storyteller ... it's from fear that people, me and Steve, might sneer. The story did not create a ripple. Star was not home. She was having dinner with the Fabian

grils

or she could have put in her two cents, having been one of the spokes also. My dad tried to listen to Notesy. "Really!" he said politely. But you could tell he had his mind on something else, the new Grandby president, probably.

After dinner I went up to my half of my room to catch up on writing this book before Steve came up. Things were happening thick and fast, and I had to get them down ... like that piece of skeleton coming in right now...