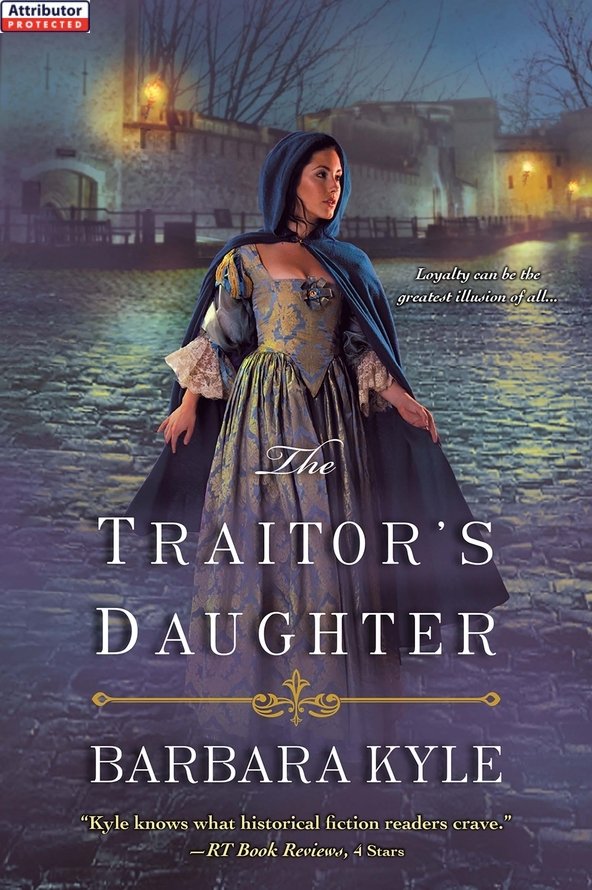

The Traitor's Daughter

Read The Traitor's Daughter Online

Authors: Barbara Kyle

Praise for Barbara Kyle's Novels

“Riveting Tudor drama in the bestselling vein of Philippa Gregory.”

â

USA Today

on

The Queen's Exiles

USA Today

on

The Queen's Exiles

Â

“A bold and original take on the Tudors that dares to be different. Enjoy the adventure!”

â

New York Times

bestselling author Susanna Kearsley

on

The Queen's Exiles

New York Times

bestselling author Susanna Kearsley

on

The Queen's Exiles

Â

“Barbara Kyle owes me two nights of sleep for writing such an enthralling book that I couldn't stop turning the pages until the final mesmerizing sentence.... The reader takes a galloping horseback ride through the feverishly patriotic and brutally violent spectacle of the Netherlands in 1572, only to slide breathlessly out of the saddle at the story's conclusion, craving the next installment of the riveting Thornleigh saga.”

âChristine Trent on

The Queen's Exiles

The Queen's Exiles

Â

“This moving adventure pulses with Shakespearean passions: love and heartbreak, risk and valour, and loyalties challenged in a savage time. Fenella Doorn, savvy and brave, is an unforgettable heroine.”

âAntoni Cimolino, Artistic Director of the Stratford Festival,

on

The Queen's Exiles

on

The Queen's Exiles

Â

“Fact and fiction are expertly interwoven in this fast-paced saga . . . this story exudes authenticity.”

âHistorical Novels Review

on

Blood Between Queens

on

Blood Between Queens

Â

“Gifts the reader with an intimate look into the minds and hearts of the royal and great of Elizabeth's England. Again, Barbara Kyle reigns!”

â

New York Times

bestselling author Karen Harper

on

Blood Between Queens

New York Times

bestselling author Karen Harper

on

Blood Between Queens

Â

“Starts strong and doesn't let up . . . Kyle's latest is extremely accessible for readers unfamiliar with the series, and the Scottish uprising, a little explored piece of Tudor history, enlivens a well-worn genre.”

â

Publishers Weekly

on

The Queen's Gamble

Publishers Weekly

on

The Queen's Gamble

Â

“Riveting, heady, glorious, inspired!”

â

New York Times

bestselling author Susan Wiggs on

The Queen's Lady

New York Times

bestselling author Susan Wiggs on

The Queen's Lady

Â

“Weaves a fast-paced plot through some of the most harrowing years of English history. There is romance, adventure, and a drama of conscience . . . what more could one want?”

âJudith Merkle on

The Queen's Lady

The Queen's Lady

Books by Barbara Kyle

The Traitor's Daughter

The Queen's Exiles

Blood Between Queens

The Queen's Gamble

The Queen's Captive

The King's Daughter

The Queen's Lady

The Queen's Exiles

Blood Between Queens

The Queen's Gamble

The Queen's Captive

The King's Daughter

The Queen's Lady

The

TRAITOR'S DAUGHTER

TRAITOR'S DAUGHTER

BARBARA KYLE

KENSINGTON BOOKS

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Praise for Barbara Kyle's Novels

Books by Barbara Kyle

Title Page

HISTORICAL PREFACE

1 - The Prisoner

2 - Enemies of the Queen

3 - The Good Doctor

4 - Blood Ties

5 - Chaucer by Moonlight

6 - The Ambassador

7 - Through the Enemy's Gates

8 - The Meeting

9 - Interrogation

10 - The Countess

11 - Confession

12 - The Signal

13 - The Visitor

14 - The Banquet

15 - Rendezvous

16 - Castle of Grain

17 - Matthew

18 - The Letter

19 - Decision at Petworth

20 - The Rescue

21 - Tower Hill

22 - Red Moon

23 - To Kill a Queen

24 - After the Storm

Q&A WITH BARBARA KYLE

Copyright Page

Books by Barbara Kyle

Title Page

HISTORICAL PREFACE

1 - The Prisoner

2 - Enemies of the Queen

3 - The Good Doctor

4 - Blood Ties

5 - Chaucer by Moonlight

6 - The Ambassador

7 - Through the Enemy's Gates

8 - The Meeting

9 - Interrogation

10 - The Countess

11 - Confession

12 - The Signal

13 - The Visitor

14 - The Banquet

15 - Rendezvous

16 - Castle of Grain

17 - Matthew

18 - The Letter

19 - Decision at Petworth

20 - The Rescue

21 - Tower Hill

22 - Red Moon

23 - To Kill a Queen

24 - After the Storm

Q&A WITH BARBARA KYLE

Copyright Page

HISTORICAL PREFACE

In 1582, Elizabeth Tudor, age forty-nine, had ruled England for twenty-three years, and under her reign the country had enjoyed peace and increasing prosperity. But her throne, and her life, were under constant threat. Religion was the cause.

Elizabeth's first act as Queen in 1559 had been the Act of Supremacy, which, without violence to Catholics, had made the realm Protestant and confirmed the monarch's position as head of the English church. Elizabeth herself advocated religious tolerance, saying she had “no desire to make windows into men's souls,” but she knew that strong leadership was needed to restrain the growing antagonism between Puritans and Catholics, and she hoped her religious settlement would unify them. It did not. Neither side was satisfied. The Puritans felt she had not taken England far enough away from “papist” customs, while Catholics considered her a heretic and found the concept of a woman as head of a church grotesque. They believed her Catholic cousin, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland, was the rightful claimant to the English throne, one who acknowledged the supreme authority of the pope.

In 1568 Mary was deposed in her own country and fled to England seeking Elizabeth's help, but Elizabeth, anxious that Catholics would rally around the Queen of Scots, put her under house arrest. Mary's supporters in England and abroad were outraged. Mary herself, though comfortably lodged in a series of castle suites, chafed at her captivity and secretly communicated with leaders who were eager to free her by insurrection or invasionâor both. In 1570 Pope Pius V issued an edict of excommunication against Elizabeth that called on Catholics throughout Christendom to rise up and depose her. This emboldened English Catholics in their opposition to the Church of England, and many refused to attend their parish churches. Known as “recusants” (from the Latin

recusare,

to refuse), these dissenters faced heavy fines.

recusare,

to refuse), these dissenters faced heavy fines.

In France, in August 1572, on the feast day of St. Bartholomew, the country's Catholic rulers instigated a savage attack on French Protestants, the Huguenots. In a convulsion of religious violence, over three thousand men and women were slaughtered in Paris by mobs of their Catholic neighbors. The carnage spread throughout France, claiming seventy thousand Huguenot lives. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre sent shock waves through England. The Protestant island nation, its population far smaller than that of powerful France, was galvanized by fear.

Elizabeth had at first been lenient with Catholic recusants. But in 1580 the threat to her became dire when Pope Gregory XIII, reinforcing the anathema against her, issued a declaration that it would be no sin to assassinate her. It was a clear license to kill. Assassination plots multiplied. Jesuit infiltrators from abroad fomented insurrection. Mary Stuart's supporters pledged to free her by force of arms. Elizabeth's government leaders discovered and thwarted the plots, but in their acute alarm they became more aggressive in rounding up agitators, real and perceived. Punishments became harsh: no longer mere fines, but imprisonment and, in some cases, death.

By 1582 England, feeling under siege, was in the grip of mind-darkening terror.

“It's all so familiar in our own deplorable time: torture . . . spies and counter-spies, the seminaries of mutually exclusive faiths, the cult of martyrdom, invasion and resistance movements . . . projects for exterminating the liberties of peoples . . . the implacable hates, the use of assassination, the division of families, the riving asunder of friends, and the conflict within the individual conscience itself, which tore men's hearts open.”

Â

âA. L. Rowse,

The England of Elizabeth

The England of Elizabeth

1

The Prisoner

London: September 1582

Â

T

hornleigh House was dark as Kate Lyon closed the door of her bedchamber, careful to be quiet. Cloak in hand, she went quickly down the stairs. Dawn pearled the lancet window halfway down, the sky luminously gray, as gray as the River Thames that flowed past the mansion. Kate glanced out, frustrated that the orchard trees obscured her view of the riverside landing. She could only hope the wherryman was there waiting. She had ordered the wherry last night. At the bottom of the stairs she turned into the great hall as the bell of the nearby Savoy Chapel clanged the hour. Six o'clock.

Two hours to go,

Kate thought. Her journey east to London Bridge would be just two miles, but the flood tide at this hour would slow her so she had to leave plenty of time. Her destination was the Marshalsea prison. Her husband had been a prisoner there for six months. At eight this morning he would be released. Kate was determined to be there.

hornleigh House was dark as Kate Lyon closed the door of her bedchamber, careful to be quiet. Cloak in hand, she went quickly down the stairs. Dawn pearled the lancet window halfway down, the sky luminously gray, as gray as the River Thames that flowed past the mansion. Kate glanced out, frustrated that the orchard trees obscured her view of the riverside landing. She could only hope the wherryman was there waiting. She had ordered the wherry last night. At the bottom of the stairs she turned into the great hall as the bell of the nearby Savoy Chapel clanged the hour. Six o'clock.

Two hours to go,

Kate thought. Her journey east to London Bridge would be just two miles, but the flood tide at this hour would slow her so she had to leave plenty of time. Her destination was the Marshalsea prison. Her husband had been a prisoner there for six months. At eight this morning he would be released. Kate was determined to be there.

She whirled her cloak around her shoulders as she crossed the shadowed great hall. The deserted musicians' gallery that overlooked the hall was a black void. Even the tapestries Kate moved past were indistinct, the light too feeble yet to fire their gorgeous silk colors or to illuminate the gold-lettered spines of the books stacked on the dining table. The books were a new shipment from Paris that her grandmother had ordered. Old volumesâthey smelled like dust. Having lived in Thornleigh House for six months Kate had become used to its two distinctive smells: old books and fresh roses, her grandmother's twin passions.

She rapped her knuckles lightly three times on the table as she passed, a small ritual developed in her visits here as a child. Always three taps. For luck? She was twenty-two now and did not believe in luck, but some childish habits never die. The Puritans would call it a pagan impulse close to blasphemy. But then Puritans could sniff blasphemy in a summer breeze.

“So you're going?” Her grandmother's voice startled her.

Lady Thornleigh stepped out from the shadows behind the stacked books. Though seventy-two the dowager baroness stood as straight as a sapling. The velvet robe of forest-green she had put on over her nightdress was tied at her narrow waist, and her silver hair, plaited for sleep, curved over her shoulder. Even in the dim light Kate felt her grandmother's dark eyes bore into her own. Kate had hoped to avoid this confrontation. Hoped their truce would hold. Straining for neutrality, she said, “You are up early, my lady.”

“You don't have to do this.” Her grandmother's voice was stern. A warning.

“Pardon me, but I do.” Nothing would stop Kate from meeting Owen when he walked through the prison gates. Her grandmother, though, stood resolutely in her way. “Please let me pass.”

“Do you know what you're doing? Don't you understand what your future will be? He will make you an outcast. From society. From our family.”

“If I am cast out it is not his doing. Nor my wish.” Owen had been arrested in a brewer's cellar for attending a secret Catholic massâan unlawful act. In disgrace by association, Kate had been snubbed by friends she had known for years.

“But it will be your lot,” her grandmother shot back. “Unless you stop.”

“I pledged my future at the altar. How can I stop?”

“By removing yourself from his bed and board. By showing that you will have nothing more to do with him. You have been a bride for scarcely seven months, you did not know his true character when you took your marriage vow. Separate yourself from him now, Kate, and all the world will approve.”

“All England, you mean.” Protestant England. Everywhere else in Europe Catholicism reigned.

“It is the land you live in, child. Its laws must be obeyed.”

If only you knew!

Kate bit back the words. Secrecy was the life she had chosen now.

Bed and board,

she thought. Of the second, her husband had none. The crippling fine handed down with his imprisonment had forced them to sell his modest house on Monkwell Street by London Wall. Owen was homeless. Kate would have been, too, but for the charity of Lady Thornleigh. Kate's father, Baron Adam Thornleigh, had made it clear she was not welcome at his house.

Kate bit back the words. Secrecy was the life she had chosen now.

Bed and board,

she thought. Of the second, her husband had none. The crippling fine handed down with his imprisonment had forced them to sell his modest house on Monkwell Street by London Wall. Owen was homeless. Kate would have been, too, but for the charity of Lady Thornleigh. Kate's father, Baron Adam Thornleigh, had made it clear she was not welcome at his house.

She lifted her head high. There was no turning back. “I am no child, my lady. I married the man my husband is, and I love the man he is. My life is with him. Nothing you say, or all the world can say, will change my mind.”

Lady Thornleigh's eyes narrowed in a challenge. “And you expect to come back here? With him? Expect me to keep a felon under my roof?”

“If you will let us bide until we can find lodging, yes. If not, we'll shift for ourselves.”

“You'll shift . . . What impudence!” Her tone conveyed indignation, but Kate now saw something quite different creep over her grandmother's face: the ghost of a smile. “Ah, my dear,” the lady went on, “you sound like my young self.” She stepped close and enfolded Kate in her arms. “This house will always be open to you, and to your husband. I must say, I admire you.”

Kate pulled back, astonished. “Admire?”

“I had to be sure you have the courage.” Tenderly, she caressed Kate's cheek, a sad look in her eyes. “You are going to need it.”

Â

The mansion was Lady Thornleigh's town house, a home away from her country estate. Its cobbled courtyard faced the Strand while its rose-trellised rear garden and orchard sloped down to meet the Thames. Moving through the garden, Kate gathered her cloak about her, feeling the river's chill dampness on the breeze. At the water stairs she found the wherryman napping in his boat, arms folded. Impatient, she rapped on the stern.

He snuffled awake. Lumbering to his feet, he made an awkward bow in deference. “My lady.”

She did not correct him. The grand surroundings and her fine clothes prompted him to call her that, but she was a lady no longer. Mere months ago she had been known as the daughter of a baron. Now she was the wife of a commoner, a felon. A Catholic.

“To Cock Alley Stairs,” she directed him. About to step aboard, she took a last glance at the house.

Bless you, Grandmother,

she thought with a grateful smile. A candle flared to life in an upstairs window. A maid coming down to light the kitchen fires, no doubt. The workday was beginning.

Bless you, Grandmother,

she thought with a grateful smile. A candle flared to life in an upstairs window. A maid coming down to light the kitchen fires, no doubt. The workday was beginning.

“Mistress Lyon?” a high voice asked behind her.

Kate turned. “Yes? Who's there?”

A boy stepped forward. He looked about ten, dirty clothes, hair like a bird's nest. The faint dawn light made a white pallor of his face. He looked unsure, as though cowed by the grandeur of the place, but Kate detected a native boldness in his eyes.

The wherryman cleared his throat. “Sorry for the fright, my lady. The lad was sitting here when I come. Said he was waiting for daylight to go up to you at the house. I told him you was coming down.”

The boy held out a sealed letter. “For you, m'lady.” The letter was as dirt-smudged as its bearer. Kate hesitated. She was used to receiving covert messages, but from couriers she knew and trusted. Surely her instructions would not come by way of this young stranger? “From my master,” the boy added.

She took the letter. “And who might that be?”

“Master Prowse.”

She could think of no such person. “A master of chimney sweeps, is he?” she asked with a wry smile. Soot blackened the boy's hands.

He looked puzzled by her jest. “No, m'lady. Master of boys. Schoolmaster.”

A memory flickered to life. “Bless my soul, not Master Tobias Prowse? Stooped old man with a wart this side of his nose?”

“Aye, m'lady. The same.”

Prowse, the tutor who had taught her and her brother when they were children. It had been years since she'd seen the old manâa lifetime, it felt, given all that had shaken Kate's world since then, but in fact it was just thirteen years ago that she and Robert had sat in their father's study reciting Latin rhymes to Master Prowse. She'd been nine, Robert seven. Even at that age her brother had been more clever with the Latin than she was. A pang of regret squeezed her heart. She hadn't seen Robert in a decade. They had been so close when they were children, inseparable, especially in that frightening time after their traitorous mother had fled with them to Antwerp. Three years later their father had got Kate back, but could not get Robert, and since then their secretive mother had again moved on with the boy, their whereabouts now unknown. It weighted Kate with guilt that she had been the one who got out, leaving Robert to endure a hard exile with their embittered mother. She could never shake the feeling that she should have done more to try to save him.

She looked at the sealed letter. A good old soul, Master Prowse. Old in those long gone days, so he must be ancient now. But why would he be writing to her? Perhaps about Lady Thornleigh's book collection? Her grandmother had been quite public in seeking donated volumes for her ever-expanding library, which she intended to gift to Oxford University. Did old Prowse, feeling his end draw nigh, want to bequeath his humble collection to her? But that was fanciful thinking. More likely the poor man had fallen on hard times and was hoping for charity from Her Ladyship and felt Kate would be his link to her. Well, no doubt his letter would make all clear. She tucked it away in the pocket of her cloak. A petitioner, however deserving, could wait. Owen could not.

The candle in the upstairs window went out. No longer needed, for the pewter light of dawn was gathering strength. Kate dug into the purse at her waist for a coin for the boy. “Where have you come from?” she asked.

“Seaford, m'lady.”

The Sussex coast. “That's a long way.” She gave him a shilling. His eyes went huge at the overpayment. “How did you come? A farmer's cart?”

“Walked, m'lady.”

Over sixty miles, and shod in rough clogs. He was no doubt hungry, too. “Knock at the kitchen door and ask them to give you breakfast. Tell them I said so.” He brightened even more at that. She asked if he had a place to lay his head tonight.

He shrugged. “I can shift for m'self.”

She had to smile at this echo of her own defiant pride. “I warrant you can.” She told him he could sleep in the dovecote in the corner of the garden wall. “But stay clear of the steward,” she warned. The man was a Puritan and known to whip vagrants.

The moment Kate was seated in the cushioned stern the wherryman pushed off. With the current against them, and the river breeze, too, he strained at his oars, and the bow bucked against the choppy waves. Kate's heartbeat quickened at the thought of seeing Owen, but beneath her excitement ran a ripple of uneasiness about the note she had received last night. Summoned to a meeting, both she and Owen. What could be so urgent that they would be sent for on the very day of his release? Kate doubted it was good news. Looking ahead at the waking city she felt a kinship with the struggling half light all around her, the night not quite yet vanquished by the sun.

Her spirits rallied in the bracing river air, and when the first beams of sun lit up London Bridge in the distance ahead her excitement rose, too. To have Owen with her again, a free man! Watching the buildings glide past she felt the great city cast its spell over her. The stately procession of riverside mansions stretched in both directions from the Savoy, their windows glinting in the rising sun. Ahead of her rose Somerset House, Arundel House, Leicester House; behind her Russell House, Durham House, York House, and the river's curve that led to the Queen's palace of Whitehall.

Across the Strand the leafy market of Covent Garden would already be bustling with people from nearby villages bringing their produce to sell. The mid-September bounty would be fragrant with fennel and fresh cresses, blackberries, quinces, and tangy damson plums. Watercraft of all shapes and sizes were busy on the river, some under sail, others under oars, some beating against the current, others gliding with it. At Paul's Wharf the first customers were calling, “Westward, ho!” beckoning wherrymen to carry them upriverâlawyers and clerks heading for Westminster, most likely. More wherries rocked alongside the Steelyard water stairs, ready to take shipping agents downriver to the Custom House quay. Kate's wherry passed a canopied tilt boat ferrying a pair of snoring, rumpled gentlemen, no doubt returning from an all-night carouse in Southwark. Fishing smacks trolled near a feeding bevy of swans. Through the still-distant arches of London Bridge Kate glimpsed lighters beetling from shore to unload cargo from ships moored in the Pool.

A peal of church bells rang the hour. Seven o'clock. She cocked an ear for the pattern: 1-3-2-5-4-6. When bell ringers rang a set of bells in a series of mathematical patterns they called it “change ringing,” and the patterns had pleased Kate for as long as she could remember. Her tutors used to sigh at her slowness with languagesâLatin and Italian had been a struggle for herâbut with numbers she was always at ease. The clear, calm beauty of mathematics spoke to her as no human tongue ever did.

Passing Queenhithe wharf she smelled the yeasty aroma of baking bread. Also, a whiff of the stinking tannery effluent polluting the Fleet Ditch. Above it all drifted the smells of charcoal, sawdust, and fish. She imagined the city coming to life. Yawning apprentices opening shops along Cheapside, milkmaids ambling down Holborn Hill, servants hefting water pots from the big conduit in Fleet Street, fishwives setting up stalls at Billingsgate. Lawyers would be hustling through Temple Bar and merchants striding into the great gothic nave of St. Paul's to do business with colleagues. On the shore by the Three Cranes Stairs a couple of mudlarks, a boy and an older girl, were bent sorting their finds from the river's sludge, intent on their task before the tide rose farther. Kate could never behold the city without a rush of affection.

Other books

The Sex Machine Rides Again (Taken By The Machine Book 2) by C J Edwards

Steel by Richard Matheson

Bond With Death by Bill Crider

Orchid Beach by Stuart Woods

St. Lucy's Home for Girls Raised by Wolves by Karen Russell

Alaska by James A. Michener

Wildflower Hill by Kimberley Freeman

From the Ashes by Gareth K Pengelly

An Honest Ghost by Rick Whitaker

Moonlight Surrender (Moonlight Book 3) by Ferrarella, Marie