The Tokyo Zodiac Murders (6 page)

Read The Tokyo Zodiac Murders Online

Authors: Soji Shimada

“That’s amazing!” Kiyoshi exclaimed, excitement momentarily showing on his face.

“So, what do you think? Based on what you know now, how do you think Heikichi’s murderer did it behind a locked door?”

“Oh, that’s easy,” replied Kiyoshi, stretching his arms above his head. “Whoever did it hung the bed from the ceiling and dropped it on his head!”

“And how did you deduce that?”

“Well, the murder weapon was flat,” Kiyoshi continued. “A panel of wood would have done the job, or even the surface of the floor. And there’s no magic about that padlock if Heikichi locked the door himself. The police found his note in which he talked about suicide, which would have been convenient for the murderer—or murderers—but in fact he died from a blow to the back of his head, which rules out suicide. So it’s got to be like I just said.”

“That’s right! You’re great, you know! The police took a long time to figure it out.”

“You mean the police thought about the bed? Oh, I’m tired of talking…” Kiyoshi sighed, disappointed.

“All right,” I said, “let me explain the theory to you. Umezawa’s bed had casters. Four people got onto the roof, removed the glass plate of the skylight, dropped a length of rope with a hook at the end into the room, hooked the bed frame, and manoeuvred the bed into position. They knew Heikichi—who was already in the bed—would be in a deep sleep from the sleeping pills. They dropped three more lengths of rope, secured the bed, and began to pull the bed up towards them. When Heikichi was in their hands, they were going to poison him with potassium cyanide, or cut his wrists, or something else that suggested suicide. But they screwed up. It turned out that pulling the bed up wasn’t so easy; they couldn’t maintain the balance. And from about fifteen feet up, Heikichi fell on his head and died.”

“Yeah, that’s it.”

“You’re such a good detective, Kiyoshi. It took the police a month to work that one out.”

“Uh-huh.”

“But what about the prints in the snow? Have you got any ideas about those?”

“Hmm…”

“Well?”

“It isn’t such a big deal, is it? The shoe prints were clustered under the window because that’s where they put the ladder. Four people were needed to pull the bed up—at least. There might have been another person on the ground, making five. That would account for so many prints in that spot. They were all ballet dancers, right? That means they could walk on

their toes, stepping carefully into the prints made by the first person. Inevitably, their prints showed a tilt. So the last person stepped on each print wearing a man’s shoes. Naturally, that limits the suspects, doesn’t it?”

“You’re a genius! It is a huge loss to the nation that you decided to become a suburban fortune-teller!”

“You see,” he went on, “criminals almost always leave traces.”

“So that’s why there were all those prints and the prints of the man’s shoe covered up all the others, as well as the prints of the ladder. You’re good, Kiyoshi, very good indeed. I hate to say this, but in fact all you’ve said has already been suggested. The real mystery starts from there…”

My words seemed to hurt Kiyoshi’s feelings. “Oh, really?” he said, curling his lips. “Hmm. Well, I’m hungry! Let’s go downstairs and have something to eat.”

The next morning, I had breakfast and then hurried to Tsunashima, where Kiyoshi’s office was located. When I arrived, he was eating ham and eggs, which he’d apparently prepared himself. The place looked like a disaster area.

“Morning! Sorry to disturb your meal…”

“Oh, you’re early today,” he said, moving his shoulder over his plate. “Don’t you have any work of your own?”

“No, I’m off today. Wow, your breakfast looks really delicious!”

“Kazumi,” he said solemnly, “what else can you see on the table?”

There was a small package.

“Yes, you guessed…” he said. “Freshly ground coffee beans. What I would really appreciate right now is some nice, hot coffee!”

“Right, how far did we get yesterday?” Kiyoshi asked me, once he had the cup of coffee in his hand. His depression seemed to have vanished. He seemed to be full of energy again, and that meant I would have to start enduring his sarcasm once more.

“The murderer—or murderers—were pulling Heikichi’s bed up to the skylight.”

“Ah, yes. There are still some parts that don’t make any sense, but I don’t quite remember what they are… I’ll tell you when my memory comes back.”

I started without hesitation. “There’s something I forgot to tell you yesterday, about Yoshio—you know, Umezawa’s younger brother, who was in Tohoku on the day of the murder.”

“He and Heikichi looked like twins,” added Kiyoshi. “But Heikichi had a beard. OK, I remember all that.”

“Well, I think those two facts complicate the story.”

Kiyoshi stared at me. “In what way?”

“It’s important, isn’t it? What if the victim was really Yoshio, not Heikichi?”

“It’s not worth talking about. After Yoshio came back from Tohoku on the 27th, his life continued as usual, right? His family saw him and so did people at the publishing companies. Neither Heikichi nor Yoshio could have deceived people who knew them that well.”

“You may be right, but everything concerning the Azoth murders might make you want to rethink this question: could Heikichi Umezawa still be alive? People, in fact, are often falsely identified. As an illustrator, I frequently meet with people at publishing companies. When I see them after I’ve been up all night, they say I look like a different person.”

“But do you really think the same trick would work on your family?”

“I don’t know, but it could work on editors if I changed my hairstyle, wore a pair of glasses, and met them only at night…”

“Did Yoshio start wearing glasses after the murder?”

“I didn’t find any record of it.”

“Well, you might possibly deceive everyone at a publishing company if they were all severely short-sighted and also hard of hearing, but not your own wife—unless she was your accomplice. But would Ayako have helped her husband even though their two daughters were among the victims?”

“Hmm… Yoshio might have had to deceive his daughters as well… Wouldn’t that be a reason to kill them? He had to kill them before they discovered the truth.”

“Look, don’t say the first thing that comes into your head. Think! What would Ayako want, then? Would she want to sacrifice her family just for a space in a new apartment building?”

“Hmm…”

“There’s an illogical leap in your reasoning, Kazumi. Or perhaps you think that Heikichi and Ayako were lovers?”

“No.”

“Did Heikichi and Yoshio

really

look alike? People tend to exaggerate details just to feel important, you know. After all, how could anyone believe that Heikichi was still alive?”

I had nothing to say.

“I don’t think there was any confusion between the brothers,” Kiyoshi continued. “I’d sooner believe that Heikichi was killed by God. He might conceivably have found someone else who looked like him and then killed him—but no, that’s crazy, too! Let’s build a firm alibi for Yoshio and then we won’t need to think about this any more.”

“You’re sounding so confident! But that will change when we start talking about the Azoth murders.”

“Oh, I’m looking forward to it!”

“You don’t know how much is involved… Anyway, let’s look at Yoshio’s alibi.”

“The police knew where Yoshio stayed in Tohoku, didn’t they? So his alibi could easily have been checked.”

“Not so easily. He took a night train to Tohoku on the 25th. The next day he said he walked beside the ocean to take photographs and didn’t see anyone until he checked into a hotel. He hadn’t made any reservations, because winter was the off-season. So he would have had enough time to kill his brother, provided he left Tokyo in the morning of the 26th and arrived at the hotel in Tsugaru that night. Yoshio’s photography was well known, and a collector visited him at the hotel on the morning of the 27th. It was only their second meeting. Yoshio spent some time with him and then left for Tokyo alone in the afternoon.”

“I see! So the pictures he took at that time would have confirmed his alibi.”

“That’s right, along with that collector. It was Yoshio’s first visit to Tsugaru in 1936. Therefore, if his pictures were not taken at that time, they would need to have been taken the year before.”

“If Yoshio took the pictures himself.”

“Yes, but he had no friends who could take them and send the film to him.”

“What about the collector?”

“If someone did that, surely he, or she, would have told the police. There was nobody who would risk jail to hide the truth for Yoshio. In any case, investigators discovered a house in Yoshio’s photos that wasn’t completed until October 1935, so his alibi was confirmed. Isn’t that dramatic? It was one of the highlights of the case.”

“Hmm, then Yoshio’s alibi is firm. He wasn’t killed in place of Heikichi.”

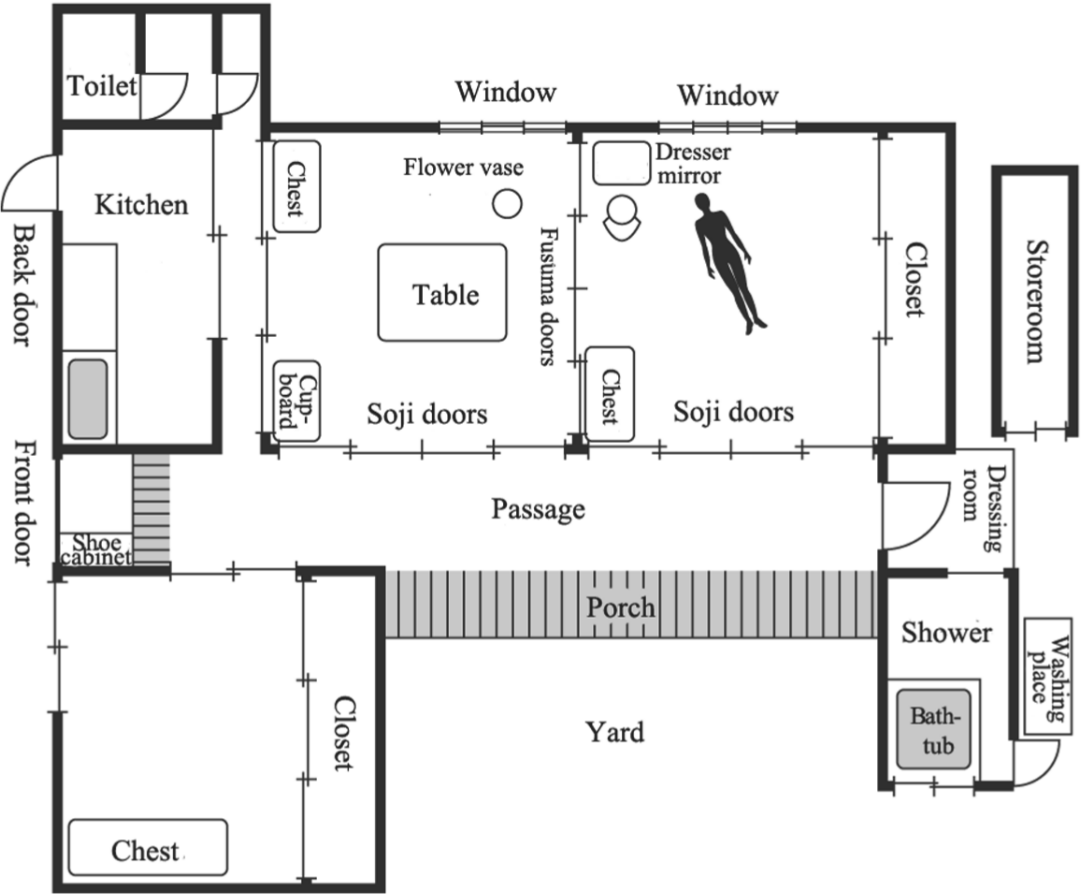

“Well, you can say that for now. Let’s go on to the next murder. Masako’s first daughter, Kazue, was killed in her house in Kaminoge between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. on the night of 23rd March, a month after Heikichi’s death. She appeared to have been beaten to death with a glass vase. I say ‘appeared’ because the blood on the vase had been wiped off. Compared to Heikichi’s case, hers was less mysterious. It may seem awful to say this, but it looked like a run-of-the-mill murder, probably by a burglar. Her rooms had been ransacked, and valuables and money had been stolen from her drawers. Even though the killer seemed oblivious to details, he had wiped her blood off the vase with a cloth or a piece of paper. If he had wanted to destroy evidence, he could have taken the vase with him, but it was left on the floor in the next room to where she was found.”

“Uh-huh. And what did the police and all the amateur detectives have to say?”

“They thought that he tried to wipe off his fingerprints.”

“I see. But what if the vase wasn’t used as a weapon?”

“There’s no possibility of that. The indentation on Kazue’s head fit the shape of the vase perfectly.”

“You suggested it was a man, Kazumi. But perhaps the killer was a woman. It would be more natural for a woman to clean the blood off unconsciously, and return the vase to its original place.”

“Ah, but there’s strong evidence against that!” I replied. “The killer was definitely a man, because Kazue had been raped.”

“Umm…”

“It seems that she was raped after she was killed. The semen found in her vagina was from a man with blood type O. Among

the people closely related to the case, only two were males: Yoshio, who was blood type A, and Heitaro, who was in fact blood type O. However, Heitaro had an alibi between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. on 23rd March.

“So the case would appear to have been an unrelated crime that happened to take place between Heikichi’s murder and the Azoth murders. Boy, were the Umezawas cursed! It gives me the chills.”

“Heikichi didn’t mention Kazue’s murder in his note, did he?”

“No, he didn’t.”

“And when was Kazue’s body found?”

“Around 8 p.m. on 24th March. That afternoon, a housewife from the neighbourhood visited Kazue with an information board about some upcoming events in the community. Kazue’s front door was unlocked, so she entered into the vestibule and called out Kazue’s name. She got no answer, so, assuming Kazue had gone out shopping, she left the information board and went home. Later that day, the housewife learnt that the information board had not been passed on to the next house, so she went back to Kazue’s. It was dusk, and the house was dark. She became suspicious. Kaminoge is a remote town along the banks of the Tama River, so she left quickly, waited until her husband came home, and then went back to Kazue’s house with him. That was when they found the body.”

“Kazue was divorced, right?”

“Yes, she’d been married to a Chinese man. His name was Kanemoto.”

“And what did his family do? Some sort of trading business?”

“They had several large restaurants in exclusive areas of Tokyo. They must have been very wealthy.”

“So Kazue lived in a big house.”

“No, it was a modest one-storey house. Some people wondered why such a rich family would own such a small house. Some people thought Kazue must be a Chinese spy!”

“Did Kazue and Kanemoto marry for love?”

“I think so. Masako strongly opposed her daughter’s marriage into a Chinese family. Because of political events then, she had good reason, of course. Kazue and the Umezawas didn’t see each other for a while, but later they reconciled. Kazue’s marriage, however, only lasted for seven years. She and Kanemoto divorced about one year before her murder. There was a lot of tension between Japan and China in the air, so the Kanemotos sold their restaurants and went back to China. The war may not have been the only problem; there must have been something else since Kazue didn’t even try to return with him. She stayed in the same house they had lived in, keeping her married name to avoid the tiresome paperwork.”

“Who inherited the house after her death?”

“Probably the Umezawas. None of the Kanemotos had remained in Japan. Kazue had no children, and, after the murder, nobody wanted to buy the house. It must have stood empty for a while.”

“An empty house in a remote area… near the Tama River… it would be the perfect secret place for creating Azoth, wouldn’t it?”

“Right. At least, most of the amateur detectives thought so.”

“Even though Heikichi said in his note that it was in Niigata?”

“Yes.”

“Did they think that the same person killed Heikichi and Kazue and then created Azoth in her house?” Kiyoshi asked.

“Yes, and with some reason. If you look at the Azoth murders, you can see that the killer acted according to a precise plan. So Kazue’s case must have also been planned. But the police only investigated the Kaminoge crime scene once! The neighbours stayed away, and so did the Umezawa women; they were all still shaken by Heikichi’s death—something that the killer might have anticipated. Things get a little confused here, though. Suppose the same killer—a man with blood type O—also committed the Azoth murders. It’s hard to imagine that someone outside the family would do it. It makes more sense if the culprit had a strong motive. Among the men, only Heitaro was blood type O, but, as I said, he had a solid alibi. At the time of Kazue’s murder, he was with three friends at De Médicis and a waitress testified to that. It’s also highly unlikely—given the scenario you’ve worked out—he could have killed Heikichi behind a locked studio door. He might have visited him to talk about business, and he might have threatened him, forcing him to swallow the sleeping pills. But if Heitaro really is a suspect, how did he manage the padlock trick? Anyway, we’ve already determined that Heitaro couldn’t be the killer. We have to think about the possibility of someone outside the family committing the crimes. I know that’s not very exciting, but I suppose we have to admit that the case doesn’t exist just for our entertainment.”

“Right.”

“I think—or perhaps I want to think—that Kazue’s murder occurred by coincidence.”

“You don’t think that her house was used as a studio?”

“No, I don’t… Although I suppose it does have the makings of a great horror novel: a deranged artist creating Azoth in a haunted house in the dark of night. Very Gothic! But, practically speaking, he couldn’t work in the dark. If he worked by candlelight, the neighbours would know something was going on and report it to the police. If I was the artist, I’d find a different house—one that was unknown and didn’t have a reputation. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to concentrate and wouldn’t be able to enjoy my wonderful creation!”

“I agree,” Kiyoshi said. “But many people still believe that Azoth was created in Kazue’s house, don’t they?”

“Yes, they believe her murder was part of the plan.”

“But if the killer’s blood type was O, and he wasn’t Heitaro, he had to be someone outside the family… So, presumably, Kazue’s case wasn’t solved?”

“That’s right.”

“Why couldn’t the police catch a burglar?”

“It’s not so unusual, if you think about it. Suppose we went to Hokkaido, killed an old lady and stole her money. The police would probably never find us because we have no connection to her. Many such cases remain unsolved. On the other hand, suspects of premeditated murders have motives that can be examined, so it comes down to confirming alibis. One reason why these murders remain a mystery is that nobody had a motive for the Azoth murders except Heikichi—who had already been murdered himself. I don’t want to believe that the crimes were committed by an outsider. It’s not at all exciting.”

“So that’s why you believe Kazue’s case was a coincidence? I see. Anyway, please describe the circumstances of her case.”

“OK. Look at the plan of her house.”