The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (48 page)

Read The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance, #Ireland

Some surgeons and apothecaries might offer you ‘tooth blanch’ to whiten your teeth, made from powdered cuttlefish bone.

28

After rubbing your teeth with the powder, wash your mouth out with white wine and ‘spirit of vitriol’ (sulphuric acid) and rub your teeth with a tooth cloth. An alternative is mouthwash. John Partridge’s recipe is simply rosemary flowers boiled in water.

29

William Vaughan claims that his recipe is better than a thousand dentifrices:

Take half a glass full of vinegar and as much of the water of the mastic tree (if it may easily be gotten), or rosemary, myrrh, mastic, bole Armoniac, dragon’s herb, rock alum, of each of them an ounce; of fine cinnamon half an ounce and of fountain water three glassfuls. Mingle all well together and let it boil with a small fire, adding to it half a pound of honey and taking away the scum of it. Then put in a little benzoin and when it hath sodden a quarter of an hour, take it from the fire and keep it in a clean bottle and wash your teeth therewithal as well before meat as after. If you hold some of it in your mouth a little while it doth much good to the head, and sweeteneth the breath.

30

If all else fails and the toothache drives you mad, you have three courses of action. The first, most civilised one is to go to a tooth-drawer, who will take the offending tooth out using a special lever called a pelican. This has a hook, which the tooth-drawer places on the tongue side of the tooth, a bolster on the outer edge of the tooth and a handle with which he levers it out.

31

Alternatively you could ask a surgeon to perform the task. The third option is to ask the local blacksmith, who will remove it with his pliers for a modest fee.

Illness

The Elizabethan understanding of why people get ill, outlined at the start of this chapter, will make it difficult for you to accept a physician’s diagnosis of your ailment. If the nature of your problem is unclear, the physician will want to know the time you started to notice the symptoms. Some physicians will calculate the position of the stars at the moment that your humours went out of balance. Most will want to know what you have been eating, in order to see whether food might be the cause. All of them will want to have a good look at your urine. Sixteen pages of Andrew Boorde’s

Breviary of Helthe

are devoted to interpreting the health of the body by the colour, substance and clarity of the patient’s urine, so a urine that ‘is ruddy, like unto gold, doth signify a beginning of some sickness engendered in the liver and the stomach, and if it be thin in substance it doth signify abundance of phlegm, which will engender some kinds of fevers’.

32

Do not be surprised, therefore, if in response to your request for

medical help, a physician sends a glass urinal for you to fill. In fact, unless you are rich, most would prefer to see your urine than you in person. For the sake of their dignity, most physicians are reluctant to get too close to their sick patients.

There is an added complication in that it is not just sixteenth-century medical assumptions that will be wrong; your own interpretation of your symptoms may be equally wayward. Elizabethan people suffer from some afflictions that no longer exist in modern England. Plague is the obvious example, but it is by no means the only one. Sweating sickness kills tens of thousands of people on its first appearance in 1485 and periodically thereafter. It is a terrifying disease because sufferers die within hours. It doesn’t return after a particularly bad outbreak in 1556, but people do not know whether it has gone for good; they still fear it, and it continues to be part of the medical landscape for many years. Other diseases have not disappeared, but have changed their character and may even have different symptoms: syphilis is a good example (discussed below). For this reason, the strangeness of the Elizabethan medical landscape is like the strangeness of the actual landscape: you will recognise the lines of distant hills, and perhaps the curve of a great river; but apart from the largest, most obvious features, very little will be familiar.

Perhaps the most difficult thing to come to terms with is the scale of death. Influenza, for example, is an affliction which you no doubt have come across. However, you have never encountered anything like Elizabethan flu. It arrives in December 1557 and lasts for eighteen months. In the ten-month period August 1558 to May 1559 the annual death rate almost trebles to 7.2 per cent (normally it is 2.5 per cent).

33

More than 150,000 people die from it – 5 per cent of the population. This is proportionally much worse than the great influenza pandemic of 1918–19 (0.53 per cent mortality).

34

Another familiar disease is malaria, which Elizabethans refer to as ague or fever. You might associate this with more tropical countries of the modern world, but in marshy areas in sixteenth-century England, such as the Lincolnshire and the Cambridgeshire Fens, the Norfolk Broads and Romney Marsh in Kent, it kills thousands. No one suspects that it has anything to do with mosquitoes; rather people believe it is the corrupted air arising from the low-lying dank marsh (hence the term

mal-aria)

. As a result, you will have no chance of getting proper treatment for the

disease. Infant mortality in and around Romney Marsh is exceptionally high, with 25–30 per cent of children dying before their fourth birthday. Overall the death rate there is in excess of 5 per cent, double the annual average, so it is like living in an area afflicted by a permanent influenza epidemic. You will find no physicians there.

35

Most local rectors and vicars live elsewhere, employing clerks to conduct the funerals, marriages and baptisms on their behalf. As one writer reports of the parishes of Burmarsh and Dymchurch, which lie within Romney Marsh: ‘both the air and the water make dreadful havoc on the health of inhabitants of this sickly and contagious country, a character sufficiently corroborated by their pallid countenances and short lives’.

36

PLAGUE

Serious though influenza and malaria are, they are not the biggest killers of the age. That title belongs to the plague or ‘pestilence’. No one knows precisely how many die over the course of the reign, but the total is probably around 250,000.

37

In 1565 the people of Bristol count up the plague victims for that year and arrive at the figure of 2,070, almost 20 per cent of the population. Ten years later, after another deadly outbreak, they record a further 2,000 fatalities. Norwich sees its worst outbreak in 1579–80, when 4,193 people die of plague, a quarter of the population, half of the victims being immigrants.

38

In 1564 plague kills two hundred people in Stratford-upon-Avon (13 per cent).

39

Exeter experiences comparable outbreaks in 1570 (16 per cent) and in 1590–1 (15 per cent).

40

This last epidemic originates in Portugal and is rought to Devon by mariners. It is ironic that the great naval ships that deliver the English from the threat of the Spanish Armada bring another danger in the form of plague.

41

In 1602 a new outbreak of plague sweeps along the south coast by way of Plymouth and Dartmouth; the following year it kills another 2,000 in Bristol and 1,800 in Norwich.

42

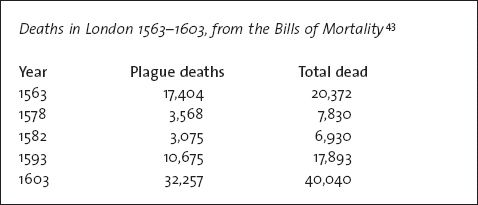

Shocking though these figures are, they are dwarfed by those for London. The plague of 1563 is so severe that the city authorities start to compile Bills of Mortality, recording the numbers of people that die in each parish. This marks the beginning of official health statistics.

The grim reality is that plague in the capital is as common as the stench of the cesspits and almost as unavoidable. You cannot predict where it will strike: people living next door to infected houses are left unaffected. Some people are not touched even when others in their own house have it.

Can you do anything to avoid the plague? The answer is: very little. Although there are no fewer than twenty-three medical treatises dedicated to it by 1600, including hundreds of recipes for medicines, none of them will help you. Nor will perfuming your room and airing it with fire save you – despite this being the official advice of the College of Physicians. But

you

have the advantage of knowing that a flea bite can convey the plague, and that the black rat that carries the plague flea does not like to move about very much, so leaving an affected area is a good strategy. Also, plague is most frequently transferred between people in towns, and it dies down in winter, when the rat population is less active. Therefore avoid towns in summer; and stay out of the poorer parishes in particular, as these are more severely affected than rich ones. It is possible that plague is occasionally passed from person to person in the breath, so be careful about gatherings of lots of people when the plague is in town (and about kissing too many strangers). Remember also that plague can be transferred from person to person indirectly, for example, through a coat worn by a plague victim.

44

It is therefore wise to avoid second-hand clothing. Change your clothes and bedclothes regularly and wash them thoroughly. The fact is that Thomas Moffet’s observation – that it is ‘no disgrace’ for a man to be troubled with fleas – probably explains why the plague spreads so quickly.

But what if it comes to the worst? What if you have painful black buboes in your groin and armpits, and experience the rapid pulse, the headaches, the terrific thirst and delirium that are the tokens of the plague? There is little you can do. Physicians will prescribe the traditional medicines of dragon water, mithridatium and theriac if they hear you are suffering, but you will suspect that these are cynical attempts to relieve a dying person of his money. The physicians themselves will not normally come near you. Simon Forman, who does attend plague sufferers, is a rare exception: this is because he has himself survived the disease and believes he cannot catch it again. However, his remedy amounts to little more than avoiding eating onions and keeping the patient warm. He has a recipe for getting rid of the plague sores that will afflict you afterwards, if you survive the disease; but that is a very big ‘if’.

45

It seems the best advice is provided by Nicholas Bownd in his book

Medicines for the Plague

: ‘in these dangerous times God must be our only defence’.

46

The important date to bear in mind is 1578. In this year the privy council draws up a series of seventeen orders to limit the spread of plague. From now on, when an outbreak occurs, magistrates in each town meet every two or three weeks to review the progress of the disease, consulting the ‘searchers’ who inspect the corpses for causes of death. The clothing and bedding of plague victims are henceforth to be burnt and funerals are to take place at dusk, to discourage people from attending. Most important of all, any house where an infected person lives is to be boarded up for at least six weeks, with all the family and servants inside, whether they are sick or healthy. Watchmen are to stand guard to make sure no one leaves. You will weep to hear the cries from a woman who has been boarded up with her husband, children and servants because one of them has been found to have the plague. People struggle to understand why the affliction has been sent upon them, why God would have cursed their family. In reality, the watchmen appointed by the JPs are not all cold-hearted; some of them interpret their role as more of a facilitator to those who are locked up: sending messages and bringing medicines and other things that they cannot get while incarcerated.

47

But still such isolation is terrifying to experience and distressing to witness.

Incredible though it may seem, if you catch the plague, old and poor women will volunteer to be boarded up with you, to clean, cook

and look after you.

48

There is a good chance that they too will die; but they will be very well paid – as much as 6s 8d or even 8s per week.

49

Six weeks’ isolation at 6s 8d per week is £2: this is the poor woman’s equivalent of the miner’s reward for breaking through the sough into a flooded mine and risking death in return for £2. But when those boards are nailed over your door and windows, plunging you into that dim purgatory between death and recovery, you could be incarcerated in your home for several months. In the case of Thomas Smallbone, of Bucklebury in Berkshire, both he and his mother-in-law die, followed by his son and wife, after which the house is inhabited by just his two remaining children and the servants. You do not want to imagine the plight of the children, especially when they too start shivering with fever. The house remains boarded up for eight months: only the servants survive.

50