The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (10 page)

Read The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance, #Ireland

PROFESSIONS

There are three distinct professions or vocations in England: the law, the Church and medicine. All three have an extended period of training, and require considerable investment. All three are the subjects of university degrees and can generate a healthy income. Schoolmasters are not considered wholly ‘professional’ because they do not need a degree and they are not normally paid more than tradesmen. Similarly, although music can be studied at a university, it does not make men rich, so musicians are not considered ‘professional’ either. Even writing books is not generally considered a ‘professional’ activity. There are no publishers paying royalties, alas, so one needs to have an income in order to be able to write in the first place. Shakespeare is one of the very few writers who manages to elevate himself from a relatively humble level to the status of a gentleman. It is a salutary thought that, although he manages to acquire sufficient wealth to buy New Place in Stratford and a significant portion of the rectorial tithes of the parish, one of the heralds dismisses his newly acquired coat of arms as that of ‘Shakespeare the Player’.

44

It is the Church and the law that offer the greatest opportunities to an ambitious man. If you rise through the ranks of the clergy to become archbishop of Canterbury, you will not only have a seat in the House of Lords, but an income of £2,682 per year. You won’t be poor if you become bishop of Winchester (£2,874) or Ely (£2,135).

45

However, the other bishoprics are worth considerably less. The archbishop of York has £1,610 per year, the bishop of London £1,000, the bishop of Lichfield £560 and the bishop of Exeter £500. The bishop of Bristol has just £294 and the bishop of St Asaph, in Wales, £187. Senior clergy (e.g. precentors, chancellors, deans, canons, prebendaries and archdeacons) may earn £50–£450 per year, depending on their diocese; but the average rector or vicar administering to a single parish will be lucky to receive more than £30 per year.

Those who profess the law can do better. When Sir Nicholas Bacon dies he leaves £4,450 of cash and silver, plus an income from land of about £4,000 per year. Sir Edward Coke is reputed to have an income of between £12,000 and £14,000, making him one of the richest men of the century; and Sir John Popham is not far behind with £10,000 per year.

46

Obviously not many lawyers earn in the thousands, but most make a decent living, in the region of £100 per year.

Medicine is the least rewarded of the three professions, both financially and in social distinction. Elizabeth does not bestow a knighthood on any of her physicians or surgeons.

47

Most wealthy Elizabethans do not pay their medical practitioners anywhere near as much as their lawyers. It is perhaps not surprising. Faced with a legal issue, an Elizabethan lawyer will serve you just as well as his modern counterpart. You would be unwise to place that much confidence in an Elizabethan physician.

MERCHANTS, TRADERS AND TOWNSMEN

Civic society too is hierarchical: another great spectrum of wealth, social status and authority. At one extreme you have the richest London merchants, some of whom have capital worth £50,000 at the start of the reign and twice that much at the end.

48

These men tend to have significant political roles, becoming an alderman (the chief representative of one of the twenty-six London wards), lord mayor or the master of a livery company. They have considerable influence; several wealthy London merchants are knighted. It is commonly said that most aldermen have goods to the value of £20,000.

49

At the other end of the social scale there are merchants who are destitute, and shopkeepers and artificers who struggle to earn £8 per year.

In most large towns about half the population have no goods or assets of any significant value. The larger provincial towns and cities in particular are dominated by a few merchant families who own virtually all the wealth. In Exeter, for instance, 2 per cent of the population own 40 per cent of the taxable property, and just 7 per cent own two-thirds of it.

50

On top of this, life expectancy is shorter, people marry later, have fewer children and a greater proportion of their children die young. Why then do the other 93 per cent not simply leave? One answer to this is obvious: where else would they go? These people rely heavily on their fellow townsmen to defend their reputations and to protect each other physically. Many have responsibilities to their friends and kin in the city. Leaving your home town is not something you do without considerable preparation or being in a state of desperation.

There are other reasons why people choose to live in urban areas. When a rich merchant becomes pre-eminent, he looks to move out

to a country estate and to set himself up as a country gentleman; therefore no English merchant family dominates a large town for long.

51

New families and individuals rise up, competing to take the place of those that have left. Hugh Clopton and William Shakespeare are both good examples of men who move to London, make their fortunes and return to their place of birth. You will find much the same in cities such as Exeter and Coventry: the mayors and aldermen are often sons of country yeomen who have come to make their fortune. Don’t think the urban rich are all born rich. The wealthy 7 per cent is not a static cohort in any city or town.

For the less well-off a city or town offers a certain reliability of income. Take Exeter, for example, which has a population of about 8,000. About 30 per cent of these are dependants under the age of fifteen, which leaves a population of adults and working youths of 5,600. About 880 of these are servants. Another 2,000 are women – 480 widows, 80 independent single women and 1,440 dependent wives.

52

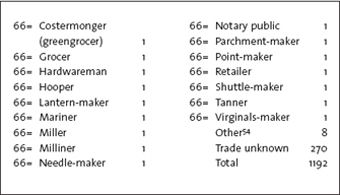

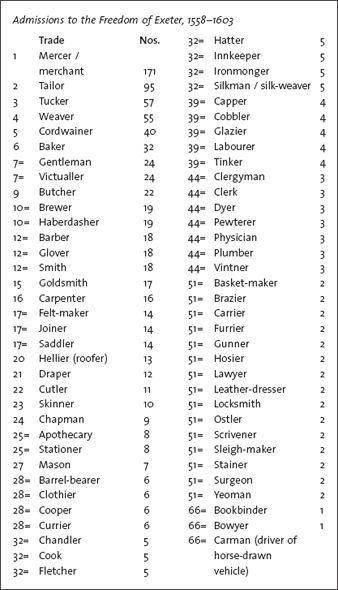

That leaves about 2,720 independent adult males. In theory, a man needs to become a freeman of the city in order to run a business. To do this, he has to be the son of a freeman, serve an apprenticeship or pay a hefty fine of £1–£5 (depending on his circumstances). How many of those 2,720 men qualify? If you examine the rolls held in Exeter’s Guildhall you will see that 1,192 individuals are admitted to the freedom of the city over the period Michaelmas (29 September) 1558 to Michaelmas 1603.

53

Given that most men gain their freedom in their early to mid-twenties, they can expect to be freemen for about another thirty-five years. Thus, in any year, about 930 of those 2,720 men are freemen of the city. In addition, there are the professionals: clergy, lawyers and medical men – and the schoolmasters whose authority to practise is normally based on a university degree or a licence granted by the bishop. These people might not own a significant portion of the wealth of the city, but they all have a considerable stake in its good management. The freemen themselves take a part in this, through electing the twenty-four aldermen who run the city. The huge inequalities of wealth thus distort our image of the satisfaction of the citizens at the time. A barber or a butcher in Elizabethan Exeter is not necessarily preoccupied by the discrepancies of wealth around him – no more than his modern equivalent is today – if he is earning enough to keep his family clothed and fed.

What about those men who are not freemen or professionals? Some are still young, with few financial responsibilities. They may be apprentices or journeymen working to save enough money to pay the fines to become freemen. Only about 10 per cent of all those becoming freemen of Exeter do so simply through the easy route of succession from their father. The remainder earn their positions. Others are employees, labourers and unskilled workers. Some are described by their contemporaries as ‘poor’, owning nothing except the clothes they stand up in. A number of those are truly destitute or are itinerant beggars looking for food (we will meet them later). Nevertheless, in a town they do at least have a chance of finding employment or a meal. Merchants are not the only ones who look at a city as a place of opportunity.

YEOMEN, HUSBANDMEN AND COUNTRYMEN

Rural areas have just as much disparity of wealth as towns. At one extreme you have the very rich, the gentry in their manor houses and stately homes, with the large incomes noted above. At the other end you have itinerant beggars and local paupers. In between you have a range of yeomen, husbandman, rural craftsmen and labourers.

Yeomen are the successors of the medieval franklins. They are ‘free men’ – not in the sense that they have the freedom of a city, but because they are ‘free’ from the bonds of servitude that applied to the villeinage in the Middle Ages. In William Harrison’s understanding,

they are ‘40s freeholders’: the rents of the land they own bring in £2 or more per year, giving them the right to vote in a parliamentary election. But who is a yeoman, who a gentleman and who a husbandman is a very confused issue. Some ‘yeomen’ could buy out quite a few local ‘gentlemen’. When John Rose, ‘yeoman’ of Shepherdswell, in Kent, dies in 1591, he leaves moveable goods of more than £1,105.

55

Another ‘yeoman’, James Mathewe of Hampstead Norris, Berkshire, leaves goods to the value of £798.

56

Add in the value of their real estate and you can see that the term ‘yeoman’ can be misleading. As a rule of thumb, apply the following gradations and be prepared to modify them when someone takes umbrage:

- A gentleman owns land, but does not farm it: he lets it to others through copyhold (if it forms part of a manor) or by lease (if it is freehold land).

- A yeoman does farm land, and might own the freehold of some of it; but he normally leases a substantial acreage. He employs labourers to help him.

- A husbandman farms land, but does not own it – normally he rents it. He may also employ helpers, especially at harvest time; but he tends to be poorer than a yeoman.

One of the reasons why yeomen like John Rose and James Mathewe have become so wealthy is that, being workers, they have little reason to spend their income in an ostentatious manner – unless they want to pretend they are gentlemen. Another is that they are better positioned to exploit the land for profit. Fixed rents – by way of long leases – and the increasing value of wool underpin the wealth of many yeomen. Some husbandmen also benefit from these conditions: their thriftiness, low rents and the rising value of their produce allow them to make a considerable amount of money. William Dynes of Godalming, Surrey, describes himself as a husbandman despite having goods to the value of £272 in 1601.

57

Similarly Edward Streate, husbandman of Lambourn, Berkshire, leave goods worth £97 to his widow in 1599 (the average is about £40).

58

There are others who make their living on the land. An agricultural labourer works in the fields on behalf of a yeoman or husbandman. You will often hear the words ‘cottager’ and ‘artificer’. A cottager is someone who, unsurprisingly, lives in a cottage and has very little or

no land except a garden. He may also have rights to graze a couple of cattle and a horse or two on the common, and to collect firewood from the manorial woods. An artificer is the Elizabethan word for a craftsman. Rural areas have a great demand for a wide range of locally manufactured products, and as you journey around the country you are bound to come across basket-makers, hurdle-makers, fishing-net-makers, charcoal burners, thatchers, knife-grinders and woodsmen, as well as farriers, blacksmiths, millers, brewers, carpenters, wheelwrights and cartwrights. Many of these people are labourers, cottagers and artificers all in one – plying a mixture of trades, labouring at harvest time, and growing their own vegetables and fruit in order to sustain themselves and their families.