The Tibetan Yoga of Breath: Breathing Practices for Healing the Body and Cultivating Wisdom (10 page)

Authors: Anyen Rinpoche,Allison Choying Zangmo

The Buddhist teachings describe this attitude of love and service toward all beings on the planet as “benefiting both self and others.” Another way of expressing this is to say, “By benefiting others, I actually benefit myself.” When we give to others, such as giving them our time, love, attention, or even our wealth and belongings, we help ourselves by freeing ourselves from our deeply ingrained selfishness. Also, by focusing on the happiness of others, we also often forget our own sorrow and loneliness in the process. For example, we may feel lonely for a close friendship, but when we see someone else enjoying a close friendship and rejoice

in that, we often forget our own feelings of sadness. The overall result is that we feel happier and more content. When finding both inner and outer harmony, connection to others and the community are key!

The theme of inner and outer harmony emerges again and again in the context of wind energy training. Spiritual health, or the state of harmony with other beings on the planet as described in Buddhist philosophy, manifests because of inner harmony, calm, and a sense of satisfaction in the mind. And by calming the wind energy in the body, we calm the heart and mind.

H

OW TO

B

EGIN

W

IND

E

NERGY

T

RAINING

The simplest way to begin wind energy training is to begin paying attention to the breath and to become aware of patterns of inhalation and exhalation. We notice how the breath changes in certain situations, and what feelings arise along with those changes in the breath.

Extensive and detailed descriptions for working with the wind energy can be found in Tibetan Buddhist teachings on Yantra Yoga. As stated above, there is no substitute for a master teacher who has had a lifetime of training. What follows in this chapter is only an introduction to this rich Tibetan Buddhist tradition—three aspects of wind energy training:

Training related to the physical body, including posture and the movement of the body, is called

the Yoga of the Body

.

Training related to the wind or the breath includes working with the breath itself, as well as the pervasive movement of the wind energy throughout the body. This is called

the Yoga of Speech

. However, in the context of this book, we will refer to it as

the Yoga of Wind

.

Finally, training related to the mind is called

the Yoga of Mind

.

Reflecting on the relationship between body, speech, and mind, we can see that the mind is the king of the body and

speech. Any expressions of the body and speech originate in the mind. When we work with the body and wind, our goal is to bring harmony, calm, and compassion to the mind. In doing so, we appease all three aspects of the wind energy.

Yoga of the Body

Yoga of the body, the physical movement and posture aspects of wind energy training and meditation practice, is very important.

The Wish-Fulfilling Treasury,

a famous text by the great Yantra Yoga master Longchen Rabjam (1308–64), describes the yoga of body in depth. This text tells us that engaging in physical yoga postures, or asanas, right before doing any wind energy training, is beneficial. Practicing asanas opens the energetic channels in the body. In the Tibetan tradition, there is a specific set of twenty asanas that are done before practicing wind energy training. When Tibetan yogis and yoginis go into caves or isolated mountain hermitages after making a serious commitment to stay in solitary retreat, they train seriously in these twenty asanas. The reasoning is that when the body’s disposition is natural and relaxed, the energetic channels in the body are also natural and relaxed. In turn, this relaxes the wind energy and the wind-mind.

We recommend practicing yoga asanas for fifteen to twenty minutes before sitting down to work with the wind energy. Here in the West, instruction in many different styles of physical yoga is readily available. All of these styles incorporate an aspect of working with the breath, and will serve the purpose of opening and softening the channels. It is perfectly fine to choose any physical yoga tradition that one finds appealing. Practicing a set sequence of asanas would be impractical, since each person has different physical abilities. Basic wind energy training is a practice that any person can work with. For that reason, we have not specified particular asanas to work with, though we do recommend a period of physical yoga practice preceding wind energy practice.

Physical Posture: The Seven-Point Posture of Vairocana

The physical posture is an important support for practicing wind energy training.

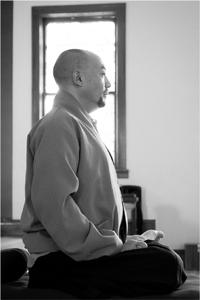

Experienced Tibetan Buddhist practitioners are already familiar with what is called the Seven-Point Posture of Vairocana, or simply the Seven-Point Posture. The “seven points” refer to seven details of the posture, and each one has a specific benefit or support role for calming the mind and readying the practitioner for wind energy training. Additionally, each has a direct relationship to the wind energy that naturally resides in different areas of the body.

The seated posture.

The first point tells us how we should sit. Traditionally, we are instructed to sit in full lotus posture. However, many of us are not capable of sitting in full lotus because we did not train ourselves to sit that way from childhood. If we are unable to sit in full lotus posture, we should work toward sitting in

Sattva posture

.

Sattva

is a Sanskrit word meaning “hero,” a spiritual hero who works for the benefit of others. Because it is less physically demanding than full lotus posture, most of us will be able to sit in Sattva posture if we work at it over time. Sattva posture is done differently by males and females, but both can begin by sitting cross-legged on the floor. Elevating the hips so that they rest above the knees makes the posture easier to hold, so we may choose to sit on a pillow or cushion. For males, the left leg is tucked in closer to the body and the left foot placed on the inner right thigh, while the right leg rests in the front. For females it is the opposite: the left leg rests in the front and the right leg is tucked, with the right foot resting on the inner left thigh. This posture is similar to a half lotus posture, except that one leg rests in front of the body for balance.

The placement of the hands.

Ordinarily the palms rest on the thighs; however, there is another technique we can use called

vajra fists

. To make vajra fists, touch each thumb to the bottom of the

corresponding ring finger, and then curl up the remaining fingers around it so it makes a fist. The fists are pressed into the crease of the thighs with the backs of the hands pressing downward and the thumbs facing away from the body. We can choose whichever hand position is comfortable for us.

The alignment of the back.

One of the most important aspects of the seated posture is for the vertebrae to be as straight as an arrow, such that one vertebra is stacked upon another. Having a straight spine is essential to our posture, the practice of meditation, and wind energy training in general. If we cannot straighten the spine when sitting on the floor, we can sit on a chair instead.

The set of the shoulders.

The shoulders should be set back like the wings of a vulture. Many of us have not seen vultures often enough to visualize what this instruction means. A vulture has a tremendous wingspan, and its wings are able to stretch out perfectly straight. Just so, our shoulders should roll back and open, or widen, so that they mimic the vulture’s broad back and wingspan. When the vertebrae are stacked straight, the shoulders naturally roll back and are set wide.

The placement of the chin.

The chin is slightly tucked in toward the neck to better invite a slightly downward-turned gaze.

The placement of the tongue.

The tongue touches the roof of the mouth, resting naturally above the teeth.

The direction of the gaze.

The eyes are open and the line of vision grazes the top of the nose. The eyes are open, natural, and unmoving.

The Seven-Point Posture supports an important aspect of wind energy training: to bring the wind energy that is dispersed throughout the body into the energetic “central channel,” which runs like a pillar through the center of the body. What is the benefit of bringing the impure winds into the central channel? Simply put, it purifies them. As we discussed in the previous chapters, by purifying the impure winds, strong emotions, conceptual thoughts, and neurotic tendencies diminish and the mind naturally becomes calm and even. This happens naturally, in part simply

by sitting in the Seven-Point Posture, even if we don’t know any other aspect of wind energy training!

Because of this very important role of the posture, it is desirable that we make an effort to develop mindfulness about all of its seven aspects, and work diligently at sitting in this manner whenever we sit down to practice until it becomes a natural habit. We may find that simply learning to sit in this posture is its own form of mindfulness training.

Yoga of the Wind

Physical posture belongs to the category of

outer yoga

. The next type of yoga we are learning here, the yoga of the wind, is called

inner yoga

.

Inner

refers to the subtle or more profound nature of this yoga, as compared with the more general nature of outer yoga. The physical posture of the body enables the central channel to open and the wind energy to enter.

Each of the seven aspects of the physical outer yoga—the Seven-Point Posture of Vairocana—are linked to

the five root types

of wind energy. These are five main types of wind energy found in the body.

The Lower Winds.

The wind energy that abides in the area above the genitals, the “secret area,” is called the lower winds, one of the five root wind energies. These winds perform the function of excretion. When we sit in the full lotus posture of outer yoga, the lower wind naturally enters the central channel. Sitting in Sattva posture supports this process as well.

The Winds in the Abdomen.

Another of the five root wind energies, the winds that aid digestion are found in the lower abdomen. When we place vajra fists in the crease of the thighs, this naturally causes the belly to poke out. When the belly pokes out, this relaxes the wind that is abiding in the lower abdomen so that the digestive winds naturally enter the central channel.

Many people in the West have the habit of hunching over. The reason for this is that we are raised sitting in chairs or sofas,

rather than sitting on the floor as is taught in many Asian cultures. When we sit, we often either bend over or lean back on something. Slouching compacts the abdomen, which closes the belly, restricts breathing, and improperly curves the spine. This means that based on our habitual postures, the central channel remains closed.

Anyen Rinpoche demonstrates vajra fist: Place your thumb under your ring finger, and close your fist around it.

Sattva posture and placement of the back of the hands on the crease of the thigh. The placement of the vajra fists on the crease of the thigh, and the male sattva posture are demonstrated.