The Things They Cannot Say (13 page)

Read The Things They Cannot Say Online

Authors: Kevin Sites

“We weren't engaging in any of the fighting while they were repairing our vehicle. But because of the fires the Iraqis set, it was raining oil. We were covered in it. It was part of our world. It's just pouring on us. It felt like rain, but it was actually oil; you couldn't fight it.”

After the LAV was fixed Shelton and his crew headed into Kuwait. “We caught up with company at Kuwaiti Airport and a scud missile lands next to us,” says Shelton. “It was earthshaking, body shaking. Here's the thing that pissed everyone off, not just me: We were supposed to clear and secure Kuwaiti airport. We get to the airport and some Marines raise the American flag at the airport and have the Kuwaitis put up their flag too. It was a photo op and you have to position yourself for a photo op! We go through all this shit and this is what this is all about, to make this good for the camera.”

After returning to the U.S. following the war in the Gulf, Shelton remained in the Marines for a full twenty-year career, but while he had job security within the Marine Corps, little else in his life was stable. The loss of the men in his unit and the image of Jenkins's charred body have stayed with him to this day. He started drinking and taking drugs after his return, but he also began an even darker and more destructive relationship that would last the next thirteen years, one that provided some evidence of the secret trauma that began long before he was ever sent to war.

“I started doing it in 1994, cutting myself with knives around the stomach,” Shelton says. “You don't want nobody seeing it but it transferred the pain. I used kitchen knives, steak knives, a few times a month. My stomach, arms and legs are pretty scarred up. Some of them needed stitches. The hair on my legs hides some of them, but otherwise they're very noticeable. I wear my pain. I had to put my pain somewhere. It helped to keep me here, the internal pain.”

Shelton also took some of his anger and confusion out on his wife. After he shoved her during an argument the Marines sent him to anger management classes. Despite his personal issues he asked for one of the most demanding leadership positions in the corps, drill instructor. Part of the screening process required him to see a psychologist.

“He asked me if I was okay and I said, âI'm good to go,' but I wouldn't look him in the eye. He knew something was wrong,” says Shelton. They approved him anyway.

So while he was preparing others to go to war, he waged another one on himself, drinking and cutting and watching everything slowly unravel. His ten-year marriage fell apart, with his wife taking their three children away, back to her home in New Jersey. When the Marines sent him to Kosovo he was jailed twice for threatening fellow Marines and they shipped him back to the States for a mental health evaluation. He got married a second time, which also ended in divorce. His life and career hung in the balance. He was besieged by both post-traumatic stress from his war experiences and the verbal and sexual abuse he says he suffered as a child at the hands of a female member of his extended family. It's a charge, he says, that his family refuses to believe and has kept Shelton estranged from them for years.

While this shattering of his sense of self may have begun before he ever set foot on the battlefield, his time in the Gulf hindered any ability he might've had left to contain it. Whether from childhood abuse or war, Shelton had lost the thread of his own story, unable to tell it, because he was unable to comprehend it. This is typical, according to psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Shay. In

Achilles in Vietnam

, Shay wrote, “To encounter radical evil is to make one forever different from the trusting, ânormal' person who wraps the rightness of the social order around himself, snugly like a cloak of safety. When a survivor of prolonged trauma loses all sense of meaningful personal narrative, this may result in contaminated identity.”

Shelton's “contaminated identity” was finally recognized by mental health professionals when he was nine months shy of retirement. VA doctors diagnosed him with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. He was put on a cocktail of antidepressants and other drugs. The only option left, he believed, was to fight for a medical disability retirement package and stay out of trouble until it went through.

Today, more than two decades after his Gulf War experiences, Shelton says he's 90 percent unemployable, living on his meager Marine disability and retirement pay. And because of the allegations of abuse he's made against a member of his family, he remains an outsider, never speaking to them even though they live in the same town. He's given up all of the drugs, prescription and otherwise, but often wanders the streets at night with little to keep him company but his scars and his dog, Rosco. He tries not to think about the war at all.

“I spend a lot of time trying to avoid it,” says Shelton. “But the physical feeling, the impact and the sounds of rounds being fired are still there. I stay home. I don't go anywhere. It's in the body, man, it's physical sensations. I don't think no one can ever be prepared, no one can ever be prepared unless you're insane already.”

Shelton feels his past has turned him into a hollow man, one without purpose or peace. But he hasn't given up the search to find them both again. He's immersed himself in different veterans' therapy programs in the effort to understand and rewrite his own personal narrative in a way that restores its meaning. One program is called Combat Paper (www.combatpaper.org), in which service members make paper out of their shredded uniforms and then use that paper to create drawings, paintings or sculptures. He's also tried his hand at writing, joining a group called Warrior Writers.

This is a piece he published on the Warrior Writers website (www.warriorwriters.org):

I'm a demon in my own life. I'm that darkness that falls on my own day, eating at my own thoughts. Destroying my own core. I'm too far for you to reach your hand out to help me because I've already given up. I am not what I show you nor what you think. I am something else. When you close your eyes you will see me, when you walk alone I am behind you, when you hear a whisper, you have heard me but I know you will not find me. What makes you think you can look for me if you know not what I am? I hear voices in my head, I hear laughter at me, I know I have failed in life and I am a tool that has been molded and slowly spiraling day by day until I am sucked in that darker place of no return only to suffer more.

While his observations, like this one, are loaded with pessimism and despair, they are at the very least, according to mental health experts, an effort at sharing the burden of his experiences and, by doing so, continuing the work of finding a better, more hopeful ending.

Postscript

After the completion of this book, Shelton wrote me a short letter about getting a chance to spend time with his children, after not seeing them for years. Despite its brevity, it seemed to indicate some small glimmer of progress . . . and maybe even hope: “Hi Kevin, I had my sons for the first time in over 7 years. I hope you are doing well and I can not thank you enough for hearing my story. It provided a huge weight off my shoulders.”

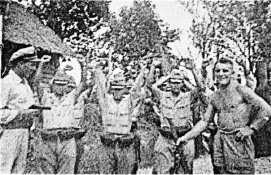

The author's father, Navy ensign Edward Sites, left, in Papua New Guinea, 1945

Intermission: The Greatest Veneration

My Father's War

L

ike so many others in the frequently beatified Greatest Generation, my father never told me about his experiences during World War II.

*

He served in the South Pacific, a young ensign who ferried Marines on flat-bottomed landing crafts to mop-up operations on the islands at the end of the war. He never told me about his time on a destroyer off the coast of Korea either.

All I knew was that he had been part of the Navy V-12 program started in 1943, designed to do two things: first, to meet the officer needs of a rapidly expanding wartime Navy and Marine Corps, and second, to keep American colleges and universities from collapsing due to dwindling enrollment as college-age men were either drafted or volunteered for service. One hundred thousand men selected for the program enrolled in public and private colleges across the country with the federal government paying tuition. They were fast-tracked through three terms over the course of a full year, followed by midshipmen's school for those joining the Navy or boot camp and officer candidate school for men choosing the Marines. Successful graduates were made Navy ensigns or Marine second lieutenants and then sent to fill the gaps overseas. My father was one of them. After completing the program he left his small Great Lakes hometown of Geneva, Ohio, to command sailors in the South Pacific. He was nineteen years old and had barely traveled outside Ohio, let alone the country. I knew he was proud of getting through the V-12 program, which, with its accelerated instruction, put a lot of pressure on its candidates, resulting in a high washout rate. But while he briefly told me about what he had to go through to get into the Navy, he never told me about his experiences once he was in the service as an officer during the war. At the time, I thought it was selfish that someone could be a part of the fabled Greatest Generation but still be unwilling to part with even the smallest anecdote. In retrospect, maybe I just wasn't persistent enough or didn't ask the right questions.

Edward Sites in the South Pacific during World War II

What I did know was what I could discern from the photographs he hung in his den and the ones he kept in boxes in the attic. They were mostly macho poses, bare chested, flag waving, not very different than the kind soldiers of today affect while deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. But out of all of them, there is only one that's held my imagination since I first glimpsed it as a ten-year-old boy. It's a picture (see page 140) of my father in his khaki uniform, a .45 in his right hand, held at waist level, pointed in the direction of two rows of Japanese prisoners with their arms raised above their heads in surrender. I remember, as a boy, seeing the photograph while digging through my father's things in the attic, but I never quite understood what the image depicted. Though I believe my brother and I may have asked him indirectly in the years after, we never got what I considered a real answer. When I went to see my parents in their retirement community, south of Tucson, a few months after I had helped create an international controversy by releasing the video I had shot as an embedded journalist of the American Marine executing a wounded, unarmed insurgent in the mosque in Fallujah, we talked about the incident, and while my parents were empathetic and supportive, I remember my father casually noting that during his deployment to the Pacific during World War II, they had orders not to take prisoners. I immediately began to wonder then about the photograph. It became an object of incongruity for meâan obsession really. My father, I had always believed, was an uncompromisingly moral man. As a small-town savings and loan executive he would return Christmas fruit baskets from clients, sending a message that he would not be swayed one way or another concerning their loan applications, whether that was their intention or not. But in this case, was my father trying to tell me that in war the same rules of civilized society didn't apply? After all, how can you agree there are going to be rules if you're already killing each other? But deep down this was my fear: Was this man who had seen me through my childhood, the doting and dutiful husband, weekend golfer and George Baileyâtype small-town savings and loan officer, also a cold-blooded killer? Could the unarmed prisoners he held at gunpoint have become his victims as well? Could my father have done what so many others had done before, justified a summary execution of those who might've killed him had the roles been reversed? Over the years, I replayed his every dinner-table utterance in my mind: the anger over what the Japanese had done at Pearl Harbor, his robust defense of the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Was there, I wondered, a dark-hearted beast under this mostly kind façade he kept?

Ironically, despite my sense of duty in reporting the truth where the mosque was concerned, I never found the courage to ask him, my own father, if he was capable of acting, or indeed had acted, in the same way as the Marine in Fallujah.

As age took away some of his agility and most of his sight from macular degeneration, I watched my father, a giant of my memories, physically shrink before my eyes. His life was now mostly about comforting my mother, also a veteran, a Navy flight nurse during the Korean War, whose back had been wracked by the abuse of an unforgiving thirty-five-year career as a surgical nurse, and listening to audiobooks provided to him by the VA.

Each time I visited them I pretended it was the time I would ask him, but instead I rationalized that it was better not to kick over that rock. I lived for years with my circumstantial suspicions but never worked up the courage to ask him directly. But that didn't stop my older brother, Tim. One Christmas when we were both visiting, Tim and I had lunch with my father in the dining room of his assisted-living residence. We were talking about the progress of my book when my brother simply blurted out, “Dad, did you ever see some real action or have to shoot and kill anyone in the war?”

I was stunned. Tim, without so much as blinking, asked the question that had haunted me, the question I was uncertain I even wanted answered. My father was silent.

He folded his arms, pausing, then cleared his throat before he spoke. “Well, you've seen the picture, haven't you,” he said. Here it comes, I thought, the very moral foundation of my belief system about to crash down around me. He continued. “You know, that one of me and the Japanese,” he said, as if he had lifted it from my brain. My brother and I both nodded silently.

I waited for him to confirm my worst fears, that this kind and honest man might be no different from most when it came to war. When ordered, he could pull the trigger and kill an enemy who had made the mistake of trusting his humanity.

“Well,” he said, “the war was already over. Japan had surrendered and we were taking them to a prison camp. That's about as close as I got.”

“You didn't shoot them?” my brother asked.

“No,” my father said, as if it were a silly question, “I didn't shoot anyone.” I finished my salad, trying to spear what was left of the lettuce greens on my plate. I couldn't look my father in the eyes, even though he couldn't really see me. I felt thoroughly ashamed that because of my own cowardice, I might've let him go to his grave with his son doubting the character he had never given him cause to doubt. But I knew I was also subtly disappointed that his moral nature had robbed me of a narrative irony too good to be true. But that is perhaps the greatest danger of telling war storiesâour desire to make them mean something more than what they are.

Postscript

Still ashamed of my wrong assumptions, I'm somewhat relieved that because of his poor vision, my father will likely never read this book.