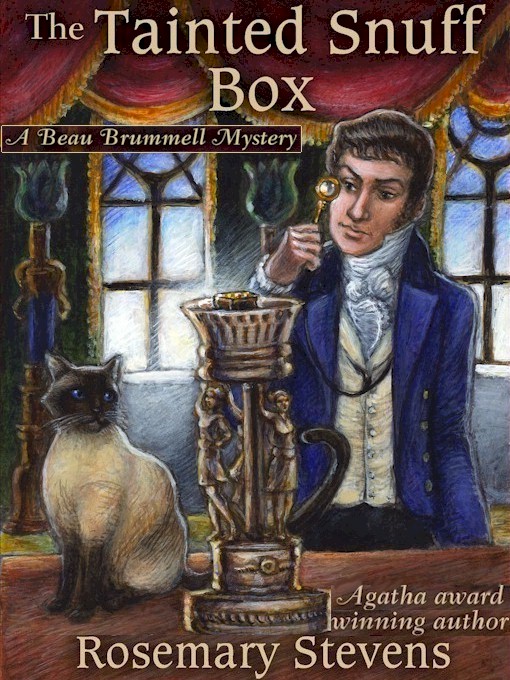

The Tainted Snuff Box

THE TAINTED SNUFF BOX

“I cannot believe anyone in England wants to kill you, your Royal Highness,” I said in a tight voice, my gaze fixed on the ceiling. “Except, perhaps, your wife.”

George, Prince of Wales, had strolled into my bedchamber at the Marine Pavilion and interrupted me at a vital moment. I had almost reached that glorious moment gentlemen eagerly strive for, the pinnacle of ecstasy some only dream of, and I did not appreciate the distraction.

Fortunately, the Prince perceived the situation at once and waved away my awkward attempt to execute a bow to him. Prinny knew my mind was preoccupied with a goal much more immediate than learning the identity of the person who had sent him death threats.

What, you ask, could be more important than the safety of the Heir Apparent? At the present moment, the creation of my cravat.

Ah, you are no doubt saying, of course.

The letters Prinny had received in London, the warnings that had prompted him to flee to his Brighton sanctuary near the sea, could surely wait while I finished arranging one of the things I am best known for: a snowy show of sophisticated sartorial splendour. One has one’s priorities, you know.

The Prince watched my every move, unconsciously mimicking the slow, careful way I lowered my head so that the folds of my cravat might settle themselves in exactly the way I desired. My indispensable valet, Robinson, stood nearby with another length of starched linen at the ready in case the white cloth around my neck proved uncooperative.

The valet’s lips pursed, a sure sign of disapproval. Robinson is a bit extreme in what he thinks is proper. Right now, I am certain he felt it right that he assist me with my neckcloth. I, on the other hand, wished to perform the Tying Of The Knot ceremony solo.

Not content with watching, the Prince could no longer resist trying his hand at the skill. Impulsively, he divested himself of his coat, stripped off his own neckcloth and helped himself to the linen Robinson held. Robinson’s blue eyes opened to their widest, his blond hair, cut in the fashionable Brutus cut, stood on end, and his lips were pressed together so tightly they threatened to split from the pressure.

“Which wife, Brummell?” Prinny asked, coming to stand next to me in front of the mirror. His fingers moved in unison with mine as I began tying the required knot. “You must be referring to that loud, unwashed, and ungraceful creature known as Caroline, Princess of Wales. Certainly you would not speak so of Maria Fitzherbert, the wife of my heart.”

Yes, the Prince has

two

wives, one legal and one not. It is a long story, and I do not wish to bore you. Suffice it to say the Prince “married” Maria Fitzherbert in l785 in a private ceremony when the lady, a staunch Roman Catholic, refused to become his mistress. She had, in fact, been about to leave him and England itself. Desperate, the Prince enacted a sensational scene in which he stabbed himself with a sword to convince her of his love. The wound was not deep, but there was sufficient blood for the ploy to work. Subsequently the wedding ceremony took place. The Prince conveniently overlooked the Royal Marriage Act which forbade the union.

Ten years—and a few flirts—later, a deeply in debt Prince ignored his first marriage and married his cousin, Caroline of Brunswick, to please his father, King George III. Need I mention a large sum of money came to Prinny along with the marriage?

Unfortunately, the cultured Prince disliked his coarse bride on sight. Somehow, he brought himself to get her with child, a girl christened Charlotte. Having done his duty—and paid some creditors—the Prince promptly returned to Maria Fitzherbert’s willing arms.

“Yes, sir, I meant her Royal Highness, Princess Caroline,” I said, inspecting the finished knot for flaws and finding none. “She might wish you six feet under.”

“Zeus! Much as I’d like such an excuse as sedition to divorce her, the truth is Caroline has as little interest in me as I do her. She’s busy with her own pursuits. Matter of fact, I hear she’s with child again. I wonder whose it is. Not mine, I assure you. I shudder to think of the making of it.” The Prince completed his cravat and turned to me for approval.

Loyally, for I am loyal to the Prince who has helped me achieve the exalted position I hold in Society,

I

refrained from shuddering at the making of

his

cravat. He had given it a jolly good try after all, and while others might deem it competent, my meticulous eye perceived a slight flaw. “May I?” I inquired, indicating the neckcloth. One must remember to observe the proprieties with his Royal Highness. Prinny is not one to tolerate the taking of a liberty.

The Prince’s royal brow creased as he nodded his permission.

I reached out and made a swift adjustment to his cravat. “There, your Royal Highness. You are the very quintessence of a gentleman.”

He smiled, well pleased with the compliment, and allowed Robinson the privilege of helping him with his coat. The valet’s lips relaxed at the honour. Prinny remarked idly, “They do call me The First Gentleman of Europe.”

A twinge of envy ran through my lean frame. The Prince could not know how his comment vexed me, though I trust no hint of displeasure broke through my tranquil countenance. For The First Gentleman of Europe is a title which, I admit, I covet. I am only human, as you very well know, and have no title and no aristocratic lineage. My father was secretary to Prime Minister Lord North in his day. Recall I am

Mr.

George Brummell, or “Beau” Brummell, if you will.

I wager that my father, who sent me to Eton and Oxford so that I might freeze, starve, and endure beatings like the aristocratic boys, would have been pleased that at the age of seven and twenty I am known as the Arbiter of Fashion. Possibly. Father had been notoriously hard to please. Even though he has been dead more than twelve years, sometimes I feel I am still trying to please him.

With the Prince properly attired, Robinson assisted me into my Venetian-blue coat. Prinny eased his ever-increasing bulk into a chair made of beechwood carved to resemble bamboo by the fire. The second week in October, this year of 1805, had brought a chill to the air. Though my bones dislike cold weather, Prinny, having passed his fortieth year, deplores it even more. All the rooms in the Pavilion are overheated, even to my taste.

My opinion had not been consulted in any matter regarding the Pavilion, I might add. The former farmhouse had been transformed into a fanciful palace with its Chinese decor becoming Prinny’s passion, a passion that shows no signs of abating. Even now, the Prince meets daily with his architects on the expansion of the house and the construction of the Royal Stables.

“Brummell, I need your help,” his Royal Highness said, interrupting my thoughts.

I signalled to Robinson that he might take himself off, no doubt disappointing the gossip-loving valet and heralding a return of the pursed lips. Retaliation, perhaps in the form of the overly aggressive usage of a pair of silver tweezers on my vulnerable brow, surely lay in store for me.

I poured a glass of Prinny’s favorite cherry brandy—awful stuff!—and handed it to him before settling myself in a matching chair. The Prince took a swallow of the liquid and looked gloomy. “Someone is threatening to kill me, I tell you. And it isn’t Caroline.”

His Royal Highness did appear worried. True, his personality normally runs to the dramatic, but this intrigue did not seem like one of his bids for attention. For the first time, I began to take his concern seriously. “Sir, you know you have only to give the command, and I am at your service. Do you have the letters you received in London?”

The Prince shook his head. “I threw the dirty things on the fire.”

“Unfortunate,” I murmured. Unwise, I thought.

“One of the letters had a spot of blood on it,” the Prince remembered.

“Abominable.” A spot of spilled wine, more likely.

“In essence, they said that London would be the

death

of me. Can you imagine?” The Prince looked incredulous. “I’ve thought it over. The culprit could be Napoleon, Brummell. The monster has assembled his army and a vast fleet at Boulogne, preparing to invade England.”

I frowned. “I know it is a constant worry that the French Emperor plans an imminent invasion of English soil. But, sir, why would Napoleon warn you to leave the capital? I should think he would want you to remain so he might take you prisoner.”

The Prince gasped at the thought, his eyes bulging in his cherubic face.

“Not that the fiend would ever accomplish such an atrocious act,” I added hastily. I reached for the decanter and refilled the Prince’s glass. After seeing him take a large, comforting swallow, I waited for him to tell me more.

“The Irish Catholics have been threatening rebellion,” His Royal Highness said in some agitation. “It could be a group from that lot.”

“Conceivably. Sir, tell me more about the letters. What kind of paper were they written on? Was the writing neat, or difficult to read? Did the writer appear to be educated?”

The Prince sighed impatiently. “Don’t ask me for petty details, Brummell. My life has been threatened!”

Why had I not poured myself a hefty glass of wine? “What precautions are being taken for your safety?”

“Several. Armed guards are posted about the Pavilion. I go nowhere in Brighton without six footmen, armed and ready to defend me, and I am carrying one of Manton’s finest pistols,” he said, patting a pocket.

I gauged the angle of the pocket to my person. Prinny is an excellent shot, but in his present state of agitation, an accident detrimental to my health—or his—could occur. “What about at night?”

“Two guards are stationed outside the door of my bedchamber, one at each of the chamber windows, and my personal valet sleeps a few feet away from me with a pistol tucked under his pillow.”

I hoped the valet did not shoot himself in the head in his sleep. Can you imagine what Robinson’s reaction would be if I asked him to sleep on a cot in my bedchamber, a piece of cold steel under his pillow? My priggish manservant would be incurably disgusted.

“I have not done listing my safeguards, Brummell. I don’t know if you are acquainted with Sir Simon, a local baronet, but he was a guest of mine at Carlton House. Though he has a large house nearby in Hove, he has been good enough to take up residence here at the Pavilion.”

My mind went through a mental list of the Nobility. “Was not Sir Simon raised to the rank of baronet after accumulating vast wealth through some disreputable means?”

The Prince pierced me with an aggravated glare. “What can that have to do with anything? The gentleman put forth a plan to me that can only show his allegiance and fidelity. He has volunteered to sample dishes from my kitchen before I partake of them in case of attempted poisoning.”

“A food taster?” I blurted, astonished at the Prince’s use of the ancient custom.

“Yes, by God!” the Prince exclaimed righteously. “Damned courageous of Sir Simon to put himself in danger like this. Honourable. You might take a page from his book, Brummell. I’m not sure you’re regarding any of this seriously enough. Come to think of it, you failed to visit me at Carlton House before I left London.”

“You wrong me,” I stated with dignity. “I could not come to you last week, as I was indisposed, and would never expose you to illness.”

No, that statement was not precisely accurate, but it was sure to appease the Prince. He is very careful of his health at all times, you know. The smallest sniffle propels him to bed.

In my opinion he did not need to know that my indisposition stemmed from my involvement in a murder investigation, rather than a disorder of the respiratory system. Perhaps you remember me telling you about the sordid situation with the poisoned milk? Ah, good, then I need not recount it again. As you know, everything had turned out all right in the end, but I cannot like the idea of Society finding out I had worked with the Bow Street Police Office.

“You are healthy now, I presume,” the Prince inquired.

“Yes. And I am indeed anxious for your safety and will do what I can to help you.”

After the Prince nodded regally, indicating his acceptance of my loyalty, I went on. “As to the author of these nasty letters, I acknowledge the existence of foreign threats. But, with your present popularity, it is difficult for me to believe any English person would want to kill you. Are there other suspects? Someone angry with you personally?”

A discarded mistress or two?

The Prince looked like a sulky child. “Might be.”

“You must tell me about it,” I urged, leaning forward in my chair. Now we were getting to the heart of the matter. “I cannot help protect you if I do not know of every possible assassin.”

“Oh, very well, then. Arthur Ainsley, one of my younger guests, has crossed my mind. Or, I should say, he thinks I’ve crossed him.” Prinny looked uncomfortable under my steady gaze. “Seems that Ainsley believes I promised to make him a peer so that he might be called to the House of Lords. Ainsley desires a Parliament seat.”