The Sun Gods (13 page)

Authors: Jay Rubin

The boss was quick to see the commercial potential of having a tall, blond waiter who could speak some Japanese. He gave Bill a black and blue

happi

coat with big, white Japanese characters on the lapels to wear along with a white

hachimaki

headband. Bill was still expected to wash dishes in his spare time, but when word began to spread about the

gaijin

waiter in Maneki who could speak Japanese, he rarely had time for that. The booths were constantly full, and some customers waited for tables to clear in Bill's section of the restaurant rather than have Kumiko or one of the other waitresses serve them.

Soon he began to have regulars, like Seiji Nagahara, a fisheries company executive. All Bill had to do was say “

Konban wa

”â“Good evening”âand Nagahara would gush at Bill's phenomenal linguistic powers. Atsushi Bando never failed to get drunk and tearfully sing “Danny Boy” in impenetrable English, proclaiming that Bill was his own, personal “Danny Boy,” whatever that was supposed to mean. Norman Miki, who worked for Boeing, was Bill's most loyal customer and perhaps the closest thing he had ever had to a public relations manager. Norman never missed a chance to promote his “act.” Every couple of nights he would show up with new friends who, he insisted, had to “see this guy.” Women customers especially enjoyed calling Bill by his nickname, Ohji-sama, and soon he was permanently established as the Prince Charming of Maneki.

With the aid of a little sake, some of the women would boldly ask him when he got off from work, or they would hand him their telephone numbers scribbled on scraps of paper. Kumiko remained ever vigilant, and when one tipsy woman of middle age began shamelessly propositioning Ohji-sama and yanking on his arm in hopes that he would sit next to her, she slapped the woman's hand and scolded her, provoking tears and apologies.

One cold, stormy Saturday night in the middle of November, Norman Miki arrived at Maneki with two new spectators for the Ohji-sama show, both of them Japanese men in their late thirties or early forties like himself. Bill smiled and bowed and welcomed them with a vigorous “

Irasshaimase

!”â“Come right in!” He gestured toward a table, and the three men began to file past him.

The last of the three was a tall, well-built man with a strong curved nose. Bill guessed he must be a successful executive somewhere: he dressed with an understated elegance that spoke of a comfortable life. But one feature of his clothing took Bill's breath away. The left sleeve of the man's beige silk sports coat was empty and pinned up to the shoulder. Bill shrunk back as the newcomer edged by him.

The man turned, glaring at Bill. In that instant, Bill was fifteen years old again, waiting for a bus that one gray morning when the green DeSoto pulled up. He could feel the cold drizzle and hear the cries of the gulls winging over Puget Sound. He knew, as surely as he had ever known anything, that this man was the driver who had emerged from behind the rain-streaked window and called him by name.

Bill tore himself away from the table and went for the tea. He felt himself moving through the smoke and commotion of Maneki, but he was no longer a part of it. Carrying the tray with the teapot and cups, he was headed down a long, dark tunnel toward Norman Miki and the stranger. When, at last, he stood before them, he saw that the one-armed man was still staring at him.

“Hey, you look a little

hen

tonight, Ohji-sama,” piped up Norman, a Nisei who always spoke English peppered with Japanese phrases. “Whatsa matter?

Neko

got your tongue?”

“Aren't you going to introduce me to your friends?” Bill asked, relieved to hear words coming from his mouth.

“Oh, sure. This is Frank Sano,” Norman said, cocking his head toward the one-armed man sitting next to him, “and this is Jimmy Nakamura. We were buddies in the 442nd.”

Norman had regaled him with stories of his outfit's military prowess, so he knew all about the Nisei fighting unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Norman always called it “the famous 442nd,” and boasted of its many military decorations, but Bill had never heard a word about it from anyone else. There had been many stories of friends lost in action and others wounded, but this was the first time Bill had actually seen someone who had brought home the scars.

He poured the men's tea and took their orders. Frank Sano's eyes were alive in a way that Bill could not define, in a way that was a little frightening.

When he served their food, Norman Miki tried to engage him in the usual banter, but Bill had only one thing on his mind. Finally, when he had a spare moment, he filled their water glasses and said directly to Frank Sano, “Are you still driving the green DeSoto?”

The others looked at Bill, then at Frank.

Frank glanced down at his newly filled glass, then returned Bill's gaze. “No,” he said, “I traded that one in a long time ago.”

“Hey, what's goin' on here?” exclaimed Norman. “You two know each other?”

Frank snorted once and, looking down, jogged his water glass so that the ice clinked against the sides. “Yes and no,” he said. “What time do you get off from work, Billy?”

“Billy?” asked Norman. “Is

that

your name?”

“It used to be,” he said, and then looked at Frank. “I'm off at midnight.”

“I'll be parked out front. I'm driving a black Chrysler now.”

At midnight, the black Chrysler was waiting at the curb, and, without the slightest hesitation, Bill opened the front door and got in.

“We'll go someplace quiet,” Frank said, pulling into traffic. “The bar in the Olympic is open all night.”

“I don't drink,” said Bill.

“Why not? You're legal now, aren't you?”

“I turn twenty-two next month. You know a lot about me, I see.”

“Not as much as I'd like to,” he said. “Anyway, we'll order you orange juice or something. I don't suppose you're a milk drinker anymore?”

Bill chuckled.

They sat at a small table by the window, the lights of Seattle spread out beneath them and bending away in a long curve tracing the edge of Elliott Bay. A lone piano played quietly at the far side of the plush room, and glasses clinked now and then.

A waitress in a short, frilly skirt took their orders, and when she left them, Bill looked at Frank. “Who am I?” he asked.

Frank smiled and shook his head. “I can tell you who you were for me,” he said.

“Fair enough.”

“The first time I ever saw you, you were four years old. We were all trying to stuff mattresses, and you kept me busy tossing you into the straw.”

“Wait, you've just gotten started, and already you're miles ahead of me.”

“This was in Puyallup,” Frank explained. “Camp Harmony.”

“âCamp What?' You mean the fairgrounds? I've been to the state fair a few times.”

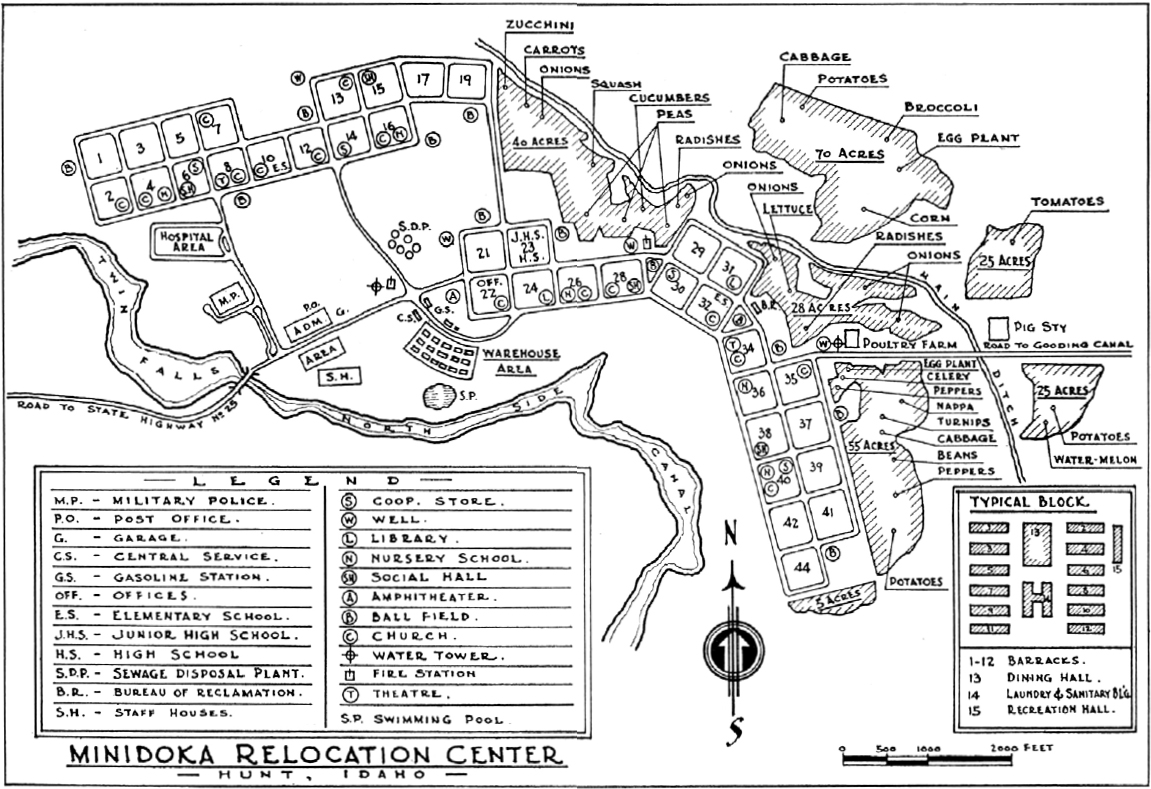

Frank looked puzzled. “All right, we weren't in Puyallup very long, but don't tell me you don't remember the camp in Idaho!”

The only “camp” Bill had been to was the Bible camp, with Clare, this past summer. He shook his head.

“You must have heard about the wartime relocation camps, at least.”

Again Bill shook his head.

“I guess I shouldn't be surprised,” Frank muttered. “No one ever talks about them anymore. It's as if the whole thing never happened. Well, it happened, all right. God-

damn

did it happen!”

PART FOUR:

1941

14

MITSUKO HAD BEEN

half listening to Tom's sermon on “Strength and Humility,” but when he brought the topic around to the present diplomatic crisis, she wished that she had not been listening at all. Could nothing be free from the taint of the Japanese military? Christmas would be here in a few weeks. What a wonderful present it would be to the world if America could convince the Japanese to get out of China.

“Even yesterday,” Tom intoned, his voice echoing through the sanctuary, “President Roosevelt showed us that humility can be the ultimate expression of strength. All through November, the militaristic government of Japan presented us with arrogance. First we heard that they were amassing troops in Indo-China, and then, a few days later, that some 30,000 troops were on the move south.”

Mitsuko wondered if her first husband, Tadamasa, was among those troops, leading his men on to more savagery. She imagined him as he had been in the early days of their marriage, a dashing sight with his thick moustache and his sword in its gleaming, black scabbard. But that had been before he had seen action; later, she had wondered if the sword was stained with Chinese blood. When he began to beat her, she sensed that it was out of shame for what he and his troops had done to Chinese women.

“Tojo told the world that Anglo-American âexploitation' must be âpurged with a vengeance,'” Tom continued, “and Togo rejected what he called the United States' âfantastic' proposals for settling the Far Eastern crisis. But just look at the strength of our good President Roosevelt. Only yesterday, as if turning the other cheek, he made a personal appeal to Emperor Hirohito to rein in his troops, cutting through all the diplomatic jargon to speak simply and humbly, from his heart to the heart of another man, in the hopes of bringing peace to a beleaguered world.”

To be sure, thought Mitsuko, the emperor was but another man. She had known that at the age of six when he was a seventeen-year-old prince whose photograph would appear now and then in the papers. She and Yoshiko and her brothers Ichiro and Jiro had been at the dinner table with her parents, answering their questions about school. For Mitsuko, it had been especially exciting, her first day of school ever, and she could still recall the ring of smiles that surrounded her at the table when she recounted the teacher's talk on their future of service to the nation.

“And what do you want to be when you grow up?” her father asked her. Without hesitation, she replied, “I want to marry His Imperial Highness, the Crown Prince, and become the Empress!” Instantly, her father's hand shot across the table and stung her cheekâthe first and last time he ever hit her.

“Sacrilege!” he cried. “Never say such a thing again!” She never dared to speak of it again, though when the prince had become engaged the following year, she had been bitterly disappointed.

“In these troubled times,” Tom concluded, “we can only pray that more men of strength and vision learn the lesson that Christ has taught us.”

Even little Billy seemed to feel something of the gravity of the mood that descended on the sanctuary; he was uncharacteristically quiet as they made their way to the front foyer. Tom solemnly wished the worshippers goodbye, the veins at his temples still bulging with the excitement of the sermon. The tension was evident, too, in the muscular flexing of his clenched jaw.

Tom had a luncheon appointment this week with ministers from some of the white churches, so Mitsuko and Billy drove home with the Nomuras. The December weather was crisp and clear, and the car heater provided welcome relief from the cold.

Luxuriating in the ease of speaking in her native tongue, Mitsuko was reluctant to part with her sister and brother-in-law.

“Come in,” she said, “I'll make some o-nigiri.”

“Yum!” Billy said. “O-nigiri. Daddy's not home.”

“What difference does that make?” asked Yoshiko.

Before Mitsuko could answer, Goro complained, “I can't stay parked in the middle of the street like this. “Let's go in. I like Mitsuko's o-nigiri.”

That settled the matter, and he found a place to park his blue Buick.

Goro stayed in the living room listening to the radio while Billy played on the floor and the women got busy in the kitchen. Yoshiko toasted the black-green sheets of

nori

over the gas flames while Mitsuko chopped and sliced the pickles: the deep purple of

shiba-zuke

, the intense green of

shiso-nomi

, turmeric's muted yellow in the disks of

takuan

.

“You never answered my question,” said Yoshiko.

“I was hoping you had forgotten. It's nothing, really. Tom doesn't like o-nigiri, so Billy only gets to eat it when he's away. Of course, he's been away a lot lately ⦔

“Is it just o-nigiri he doesn't like? Look, don't think I didn't notice Billy was calling you âMommy' for a while. He still slips occasionally. Is that another privilege he's allowed only when his father is away?”

Mitsuko concentrated on slicing the translucent amber

nara-zuke

as thinly as possible, and before she could answer, Goro charged in from the living room.

“

Taihen da!

” he shouted, the round lenses of his spectacles shining in the kitchen light. “What awful news! The Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor this morning!”

Yoshiko clucked impatiently and proceeded to fold and cut the

nori

.

“Those poor natives,” said Mitsuko, shaking her head.

“Natives?! What are you talking about?” shrieked Goro. “Pearl Harbor's in Hawaii! The Japanese are dropping bombs on America, you idiot! This means war! You should have heard the announcer. He must have been foaming at the mouth!”

Mitsuko looked at her brother-in-law crossly, more annoyed at the tone of voice he was using with her than struck by the news.

“It can't be that bad,” said Yoshiko. “Some crazy person set off a bomb.”

“A fanatic,” said Mitsuko. “They'll catch him.”

The women's placid reaction had its effect on Goro, but he maintainedâif now in a calmer tone of voice, between mouthfuls of o-nigiriâthat they were underestimating the importance of the news.

The more Goro talked about war, the more vividly Mitsuko could imagine Tadamasa wielding his sword. She was glad when he and Yoshiko left shortly after the meal.

The Nomuras had been gone little more than ten minutes when the telephone rang. It was Yoshiko. “Mit-chan, we've been robbed! They tore the place to bits.”

“Did you call the police?”

“Yes, just now.”

“I'll be right over,” said Mitsuko. “I'll take a cab.”

She did not even finish putting away the leftovers, but more than fifteen minutes had gone by before she managed to ready herself, bundle Billy into his winter coat, and hurry down to the street. A cab came by immediately, but the driver looked at Mitsuko and sped away. They walked to Broadway, but most of the cabs were occupied, and yet another driver of an empty cab passed her by. Finally, one stopped for her, and more than three quarters of an hour after Yoshiko's call, Mitsuko and Billy stepped out in front of the Nomuras' small frame house on East Olive Street.

A stocky policeman stood in the doorway, night stick in hand.

“Where do you think you're goin'?” he demanded as she approached the front door with Billy.

“I am Mrs. Nomura's sister. She called me about the burglary.”

“Burglary? What burglary?”

“They were robbed. Isn't that why you are here?”

“Look, little Jap lady, I don't know nothin' about no burglary. I'm just here to guard the place. Now, you better get goin'.”

“Guard? What do you mean? I want to see my sister.”

“She ain't here, so get goin' now before I have to arrest you.”

Mitsuko knew her sister was inside, but there was no point in arguing with him. She led Billy back down the front walk to the street, from which her cab had long since disappeared. A few cars drifted by, some of the drivers gawking at the policeman conspicuously stationed at the door.

Mitsuko turned to look at him again, and he waved her away with his night stick. All but dragging Billy, she hurried down the street and turned the corner. Down half a block, she came to the fence-lined back alley. At the rear of the Nomuras', she peered through a crack in the fence. Just as she had feared, another policeman was stationed at the back door.

“Billy, let's run!” He scurried after her to Madison, where she found a public telephone. Her breath clouded the glass of the phone booth. She dropped in a nickel and dialed Yoshiko's number.

A man answered the phone, and when Mitsuko asked to speak to her sister, he would say only that the Nomuras were “indisposed” and could not come to the telephone. No amount of explaining seemed to budge him, and eventually he hung up.

She dialed home and Tom answered.

“Mitsuko, where are you?” he demanded. “I've never seen this place in such a mess. That Japanese food of yours is spread all over the place.”

“Tom, please.” She explained the situation and gave him the exact location of the phone booth. In the ten minutes it took him to drive there, she began to shiver.

They went to the Nomura house, where the policeman was now walking up and down and rapping his hand with his stick in an apparent effort to keep warm. Mitsuko hunched down in the car while Tom stepped out to speak with him. The policeman kept shaking his head. He eventually noticed Mitsuko, and the look on his pink face changed to a sneer.

“He wouldn't tell me anything,” Tom growled when he was behind the wheel again. “Except it's got something to do with the FBI.”

“What is that?”

“The Federal Bureau of Investigation. The national police.”

Mitsuko had heard horror stories involving the Japanese national police, the so-called Special Higher Police, who lurked in every corner of the nation and pounced on anyone who dared to whisper criticism of the emperor or the government.

“I didn't think there was such a thing in America,” she said. “But why are they keeping my sister?”

“I don't know,” Tom said, “but it must have something to do with Pearl Harbor.”

Back home, Mitsuko tried several times to reach Yoshiko by telephone, only to have the same man tell her that her sister was “indisposed.” Tom spent the afternoon by the radio. Finally, as the sun was going down, a call came from Yoshiko.

“They took Goro!” she wailed. “They're gone. Please come over.”

“We'll be right there,” Mitsuko assured her and hung up.

Reluctantly leaving his radio, Tom drove Mitsuko to Yoshiko's, Billy singing to himself in the back seat.

Tom said, “The Treasury Department has impounded all Japanese investments. I wonder what this is going to do to Goro's bank?”

In tears, Yoshiko greeted them at the door. Before they had their coats off, she started telling them what had happened. She and Goro had driven straight home after lunch and found that the house had been broken into. Assuming they had been burglarized, they had called the police, but found nothing missing. The police arrived a few minutes later along with a half dozen FBI men. It was the FBI, not burglars, who had broken into the house while the Nomuras were eating lunch with Mitsuko. Goro had asked indignantly if they had brought a search warrant with them, but they had acted as though they resented such a presumptuous question. A few minutes later, four of the FBI men had taken Goro away, leaving one man to answer the phone and another to prowl around while a policeman guarded each door.

“None of them would tell me what it was all about,” said Yoshiko, “but when I asked if it was connected with the bombing in Hawaii, they smiled in a nasty way.”

Tom telephoned the FBI, but no one would talk with him. He drove downtown to the FBI office, but he was turned away at the door. It was decided that Mitsuko would spend the night with Yoshiko, and after Mitsuko cooked a simple dinner for them, Tom took Billy home.

The two women were startled when a car pulled up at the house after eleven o'clock at night and the doorbell rang. It was Tom, holding Billy, who was in pajamas and wrapped in a blanket, his eyes red and teary. The boy had been screaming his lungs out for Mitsuko since bed time, Tom said. He thrust his son into Mitsuko's arms and drove back home.

Yoshiko said she could not sleep, and Mitsuko kept her sister company well past midnight, but Yoshiko was up first thing in the morning to wait for the newspaper, and as soon as it came, she began reading the horrifying news to Mitsuko. They learned of the American ships sunk in Pearl Harbor and the loss of life, but it was when she turned to page three that Yoshiko began to whimper.

“My God, listen to this! Someone made a threatening phone call to the Japanese Baptist Women's Home and now the police are standing guard. And someone threw stones through the windows of two Japanese grocery stores. And this is even worse: âNumerous calls were received by police from citizens who offered their services, some of them volunteers expressing a wish to help intern Japanese residents.'”

She looked grimly at Mitsuko. “They're going to lock us up,” she said.

“It must be some crazy people saying those things. The government wouldn'tâ”

“Here it is!” Yoshiko cried before Mitsuko could finish. “This is about Goro: âForeign-Born Japanese Rounded Up.'”

Yoshiko began reading silently.

“What does it say?” Mitsuko pressed her.

“Wait, wait,” she said, shaking her head and moaning. “Listen: âJapanese who have been kept under surveillanceâ'”

“Under what?”

“Under surveillance: being watched by the police.”

“Just like in Japan! But why would they be watching Goro?”

“âJapanese who have been kept under surveillance were taken into custody by police for the FBI. They were taken directly to the immigration stationâ' That must be where Goro isâ'and their personal effects, cameras, Japanese documents, firearms and certain other possessions were held at police headquarters.' His keys! They took his house keys, his car keys, his office keys, even his safety deposit box key.”