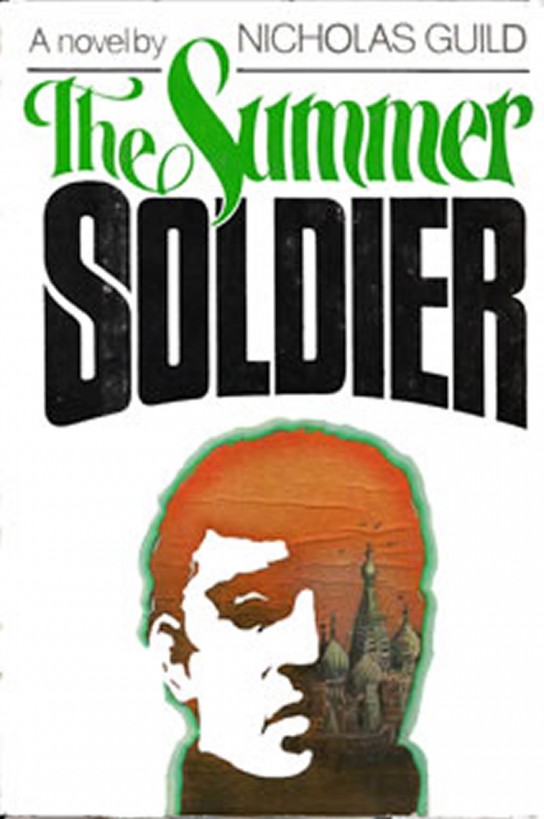

The Summer Soldier

a novel by

Nicholas Guild

Published by Nicholas Guild at

Smashwords.com

Copyright © 1978 Nicholas Guild

This ebook is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If

you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not

purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com

and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work

of this author.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

From

where he was standing on the driveway, he couldn’t see much

evidence of fire. Of course the roof and front wall of the house

had been pretty thoroughly hosed down and one pane of glass in the

dining room window inexplicably broken, but the kitchen, which

occupied a rear corner, had sustained all the real damage.

They had even hosed down the garage door,

which you would have thought well out of reach of the flames. He

swept a hand over its beaded surface to leave a glistening smear.

His palm, he noticed, came away covered with a milky film.

Louise had never really liked that color.

“Well, look, if you think it’s that bad I can

take it back. I’ll just tell the guy it doesn’t look anything like

what he showed me on the sample card.”

Twisting around from his crouch by the lower

left hand panel, careful to hold the paintbrush so it wouldn’t run

out onto where the cement wasn’t covered with sheets of newspaper,

he had caught sight of her standing on the sidewalk, just at the

edge of what, God willing, would sprout into their front lawn. She

had peered through the blinding early afternoon sun, shading her

eyes with one hand as she rested the other, tucked under at the

wrist, on her hip.

It was a characteristic attitude.

“No, forget it. I can live with it. And you’d

have to repaint the whole door.” He remembered how the hand shading

her eyes had dropped suddenly, falling loose and despairing at her

side. “Oh, Ray. What the hell.”

“Mr. Guinness?”

Someone from behind had taken hold of him,

just at the base of the triceps, and, without thinking, Guinness

snapped his arm forward to free himself. It was nothing more than a

reflex, the kind he had once honed carefully but had thought long

buried and forgotten, so when he stepped back it wasn’t to drive

his elbow into anybody’s larynx. He even smiled, feeling slightly

embarrassed at the expression of surprise on the face of the man

behind him. The guy was only doing his job.

“Mr. Guinness,” the man said again,

recovering himself almost at once. He was the earnest looking young

detective with the tightly curling, sand colored hair—a nice kid,

about twenty-six or so and working very hard on his professional

dignity. “Mr. Guinness, I’m afraid we won’t be able to let you into

the house. Can I take you anywhere? Some friends, perhaps?”

Ray Guinness didn’t answer immediately.

Instead he glanced down at the driveway, touching an eyebrow with

the tips of his first two fingers, as if to make sure it was still

there. He must have looked puzzled.

“For the night, Mr. Guinness. You’ll have to

have somewhere you can go for the next several days. Our laboratory

people will have to keep the house sealed for some time. Until

they’ve had a chance to sift through everything. There will have to

be an arson investigation as well. We’ll bring you out any clothes

or personal effects you need, but I’m afraid we won’t be able to

allow you inside. I’m sorry.”

The young man seemed almost to be pleading

with him to understand, as if he expected torrents of abuse.

But Guinness understood. Yes, it would be

dark in another hour and he would have to begin thinking about a

place to sleep. A hotel. He couldn’t think of anyone who was a good

enough friend that he could ask them to put him up, not under the

circumstances. At least not anyone he wanted the cops knowing

about. No, it would have to be a hotel.

The place was crawling with police. It looked

like every plainclothesman in the Bay Area was on his planter box

of a front lawn. They stood around in little knots, talking quietly

among themselves like guests at a party that hasn’t yet quite

gotten itself off the ground.

“When can I see my wife?”

Curly didn’t much like that. He too glanced

down at the cement, his face hardening with worry.

Everyone was being very cute about Louise; no

one would tell him where she was or precisely what had happened to

her. Except that she was dead.

The police had brought Guinness home. They

had come and fetched him from his office, where he had been

patiently working his way through a seven inch stack of sophomore

term papers. Just as he had finished the first reading of one

comparing Troilus and Sir Gawain as courtly lovers, there came a

light tapping on the glass upper panel of his door. The door had

opened before he had had a chance to respond.

“Mr. Guinness?” It was Curly, standing with

only half of his body across the sill. “Mr. Guinness, would you

come with me please,” he said softly, holding out his gold badge.

‘‘I’m afraid there has been an accident.”

He wasn’t told that his wife had been killed

until after they had gotten him there. But he had guessed.

Curly—was his name Peterson? He thought so, yes it sounded

right—Detective Peterson had been very reluctant to say much. He

gave the impression of having been ordered to keep things dark, or

maybe he just didn’t fancy his charge getting hysterical on him at

forty miles an hour. Anyway, he was acting the way people do when

someone is suddenly dead.

They had parked most of a block down from the

house, and as he got out of the car Guinness had caught sight of a

man in white coveralls stepping into the rear of a police van and

closing the double doors behind him. For just a second the inside

of the van had been visible, and there was what looked like a

litter on the floor and on the litter was something covered with a

black plastic tarp.

Had that been Louise?

So when he had finally been told, it hadn’t

been much of a surprise. But death had stopped being much of a

surprise a long time ago.

A Sergeant Creon had been the one to break

the news, if you could call it that: “There was a body found in the

house. Female, Caucasian, a hundred and ten to a hundred and twenty

pounds. About five foot four, with dark brown hair worn to the

shoulder. Wearing a printed cotton house dress, dark tan with

pictures of fruit on it. We assume it to have been Mrs. Guinness.

That sound about right?”

“We assume it to have been Mrs.Guinness.”

Guinness swallowed hard and nodded. He had been married to the

woman for five years, and now she was just a series of identifying

characteristics.

“Sorry,” Creon responded nervelessly, not

even bothering to look up from the little pocket book in which he

was making notations. A few seconds later he closed it and

sauntered off without another word. Guinness watched him go,

measuring his back for an appropriate sized bullet hole.

Not a gent you warmed up to right away.

Could that really have been Louise? Five feet

four in a tan dress. Yes, that was her. It had to be her. Still, it

was hardly possible to think of her as a corpse.

Sadly, it would no doubt become easier. It

always happened that way.

“They might be able to let you see her

tomorrow,” Peterson answered finally, apparently having made up his

mind that it would be safe to risk that much. Creon must have been

a real peach of a guy to work for. “They will have finished the

preliminary examination by then, and there will have to be a formal

identification. I should think by tomorrow, but you had better

check with the sergeant.”

The hell with the sergeant. He would be

seeing Louise soon enough in any case. What there was to see.

When had been the last time—breakfast? No,

lunch. He had come home for lunch. He always came home for lunch on

Thursdays, and it was a Thursday. Somehow it seemed important and

strangely difficult to keep such things straight.

Yes, he had come home for lunch. On Thursdays

he had two hours between his morning and afternoon classes, and so

there was time to come home.

Louise had been wearing that dress. She

called it her French dress because all the little printed apples

and onions were labeled underneath and the labels were in French.

She always wore that dress whenever she planned to do a lot of

dusting. He hadn’t the faintest idea why.

So they had had lunch together, or at least

she had served him his lunch. She didn’t eat lunch very often,

saying it was hard on her waistline, but she had sat at the table

in the little breakfast nook off the kitchen and had kept him

company while he ate. That had been—when?

Not quite seven hours ago. He had had a ham

and cheese sandwich and a glass of iced tea.

Had they talked? Not precisely, no. She had

talked and he had eaten, putting in a yes or a no as the situation

seemed to demand. She had been after him to do something, but for

the life of him he couldn’t remember what it had been. Would it be

important later that he should remember? What had she been talking

about?

Yes, of course; it had been something about

the venting for the clothes washer in the basement. It was backing

up, and she had thought perhaps one of the hoses was clogged and

wanted him to check when he got home from work. He couldn’t do it

right then because he would have had to change out of his slacks

and jacket and there hadn’t been time.

No, he couldn’t imagine that it would be

important to remember that.

They had sat there like that for maybe half

an hour. Him eating a ham and cheese sandwich, thinking with one

half of his mind about how that afternoon and evening and the next

and the whole fucking weekend were hostages to his sophomore term

papers, and with the other half helping her worry that perhaps it

might be something major with the washing machine, something he

wouldn’t be able to fix with a pair of pliers and a screwdriver and

a straightened clothes hanger. He would have liked to have stayed

and seen if he couldn’t have taken care of it right then and there,

just so she wouldn’t have to spend the whole afternoon tormenting

herself over it.

And now she was so much cold meat in some

locker in a police morgue.

A light blue Chevy sedan, identical except in

color to the half dozen or so police cars parked along the street

in both directions, pulled into the curb in front of the driveway

and stopped. On the driver’s side the front door opened and a man

with black hair pared down to a crew cut got out and slammed the

door shut behind him. He wasn’t very tall, so it wasn’t until he

came around to the trunk of his car and bent over to open it with a

key that his slate gray suit appeared to be a couple of sizes too

large for him.

Out of the trunk came a small black satchel,

and the man with the crew cut and the baggy suit carried it into

the house, amiably waggling his free hand at Creon as he passed.

The good sergeant wasn’t wasting any time in getting his sifters

out on the job; probably by morning they would have collected

enough fingerprint cards and samples of carpet fluff to keep them

all out of mischief for a month.

Accident hell. Louise hadn’t had any

accident. Nobody dies in a stupid little kitchen fire, not in a

kitchen from which there are two exits and which isn’t much bigger

to begin with than a good sized bathroom.

Something was going on here that nobody was

telling him about, and he didn’t like it. Louise hadn’t simply set

fire to the place and died. Louise didn’t have accidents, she

wasn’t the untidy type.

She even kept a small fire extinguisher,

shaped like a can of whipping cream, in a drawer on the left hand

side of the sink. No, Louise wasn’t the type to have accidents.