The Suitors (26 page)

Authors: Cecile David-Weill

I’m running a little low …

“Oh, God,” I moaned.

What should I do? I had no idea, none, and was too devastated to think. I couldn’t help recalling a misadventure I’d had a few years earlier, however: eager young psychoanalyst that I was, I’d confronted the cleaning lady I’d recently hired about her alcoholism, which I had diagnosed from the falling level of my liquor bottles. I’d been soft-spoken, supportive. And she’d been so touched that to my surprise she had given up drinking. So I was rather pleased with the help I’d given her—until she decompensated into schizophrenia, which until then had been anesthetized by alcohol. And that had taught me once and for all about the limits of therapeutic discourse.

My mother must have found a form of equilibrium between tranquilizers and cocaine. And aside from the fright she’d had over her nosebleed, there was no indication that she wanted to stop. Why not simply give her the name of a psychiatrist? Because I did

not

see myself having a word with her about the situation. All the more so in that she was probably less than eager to talk

things over with me or any other member of the family. And then I wondered: was her addiction an open secret, a problem I was the last to discover? For in spite of my illusions of shrewdness in psychological matters, I was doubtless, like all children, in a particularly poor position to see my parents with clarity and understanding. Did my father know what was going on? I had to sound him out as soon as possible.

.

I found my mother having tea in the loggia with Laszlo, Gay, Frédéric, and the Démazures. In good spirits? Overexcited? I tried to look at her in a normal way in spite of my suspicions, which I sensed would be difficult to shrug off.

“But … where is Odon?” I exclaimed, with a gaiety intended to mask my concern. “If he were here, the Little Band would be at full strength!”

“Not back from Vallauris yet. Listen, I’ve entrusted Charles with a mission. He was at such loose ends … and as it would never occur to him to open a book, I had to keep him occupied.”

“You know your mother,” added Laszlo. “A heart of gold. She had the bright idea of asking Charles to do her the favor of organizing the wine cellar. So don’t be surprised if you see him emerge in triumph from the lower depths, because he surfaces from time to time to give us bulletins on his progress.”

“He’s phenomenal!” confirmed Frédéric. “Speaking of which, after the wine cellar, you ought to sic him on the library so he can arrange all the books in alphabetical order.”

I suddenly felt completely alone. Which was only natural, since I hadn’t talked to Marie all weekend, and given that nothing was likely to change on that front until Béno’s departure, I decided to go down to the beach in hopes of running into my father.

“Oh! Just the person I wanted to speak to,” he said, coming out of the water. “Georgina went on up already. You didn’t see her? She’s not well, and I’m worried about her, she seemed both wild and depressed. In fact, she scared me a little.”

“Yes, because you didn’t know what to do, but maybe she is just sad and that proves she’s alive.”

“You want to know something? It’s lucky your mother isn’t that way!”

“You think so? I’m not sure about that …”

“No, believe me, beneath that fragile exterior, she’s a rock! In fact, I’ve always preferred women like Flokie to those who seem like tough gals when they’re really spun glass, like Georgina. Because me, I need someone solid to lean on.”

MENU

Asparagus Vinaigrette

Poularde Mancini

Salad and Cheeses

Apple Soufflé

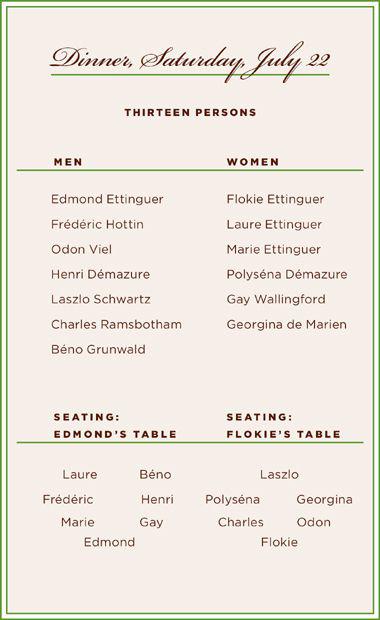

Entering the summer dining room, I saw that my mother had seated everyone very nicely: she had kept Odon and Laszlo to help her with Charles (whom she hadn’t brought herself to seat on her right), while sending Frédéric and me to liven things up at my father’s table, where we’d been placed the previous evening.

Slipping a knife under his plate to tilt it and so pool the vinaigrette from the asparagus, Frédéric began teasing Béno.

“You’re a financier, a collector, a jet-setter, a man of property, and who knows what all else. And I heartily approve, as I myself am a night owl, a playwright, and a pillar of this house. But some would say that you’re spreading yourself too thin. Don’t you ever, as I do, worry that you’re doing everything the wrong way?”

“Oh, you’re right, I probably do everything wrong. What do I do well? Let’s see … Oh, yes: I sleep well!”

Yes, Béno certainly had the gift of charm. But he was still driven to vamp his audience, because he now undertook to explain to us his family’s crazy lexicon based on favorite anecdotes, such as the “Your Uncle Syndrome.”

“It all started with the fact that my great-uncle was as puffed up as a marshmallow with his own importance. He was a bureaucrat of the utmost obscurity, yet he thought himself so closely engaged with momentous events that he felt he was on an almost equal footing with the great men of his day. Convinced of this herself, his wife used to tell us, for example, in accents of deep concern, that ‘your uncle is angry with de Gaulle’ whenever the president (whom my uncle had never met) had taken a decision that displeased him. As if de Gaulle always took my uncle’s opinions into account when he decided on a course of action, and chose to ignore his opinion only to exasperate him. Ever since, whenever someone takes himself for God’s gift to creation and puts on airs, we say he’s

your uncle

.”

“Well,” observed Henri Démazure, “then it seems certain French writers suffer from the same syndrome, because I know some people who write biographies of great men simply to compare themselves with them.”

“Just whom did you have in mind?” inquired Gay.

But my father, fearing a tedious detour into Left Bank gossip, made a preemptive strike: “Have you got any more like that, other family expressions?”

“Oh, yes, for example,

the little wild strawberries

.”

“The what?”

“It’s a term we invented for people who imagine that there’s nothing like a dollop of criticism to properly season a compliment. For example, saying ‘Your dress is ravishing,’ then adding, to be more convincing, ‘I can’t say the same for your coat.’ It seems idiotic, but you wouldn’t believe how many people do that.”

“But what does that have to do with wild strawberries?”

“Nothing. The name comes solely from the time a guest at my grandparents’ house in the country, wishing to be gracious about the strawberries served for desert—a luxury at the time—along with some wild strawberries picked by the children, had exclaimed, ‘These strawberries are delicious! Not like the little wild strawberries, which are awful!’ ”

“Wonderful!” my father said, laughing. “Sorry, dear,” he told me, “but after all, it is a more poetic way of describing people than the psychologizing jargon of today!”

“Yes, I see what you mean,” observed Gay. “It’s the triumph of Proust’s maladroit Aunt Léonie over Flaubert’s cataloging obsessives, Bouvard and Pécuchet! ”

“Precisely!”

Seeing a chance to take over the conversation with a nod to me, Henri Démazure began to defend my profession.

“Psychiatrists are fascinating, though! I’m reading a book now by one of them, Patrick Lemoine, in praise of … boredom! In fact it’s called

Being Bored, How Wonderful

, published in 2007 by Éditions Colin …”

“Oh, really!” said Gay, scratching her dog’s ears under the table.

“Anyway, Lemoine talks about two sorts: pathological boredom, a symptom of psychiatric illness, and the normal kind, which he considers indispensible for the construction of the self.”

After a swallow of Gruaud Larose, Henri pressed on: “He claims that when children are bored, they develop their imaginations and become more independent in a natural way, and that without boredom, their healthy individuality and creativity would be compromised. But these days, parents are growing less and less tolerant of boredom in their children’s lives. Just consider how they drag them from the soccer field to the swimming pool or a tutoring session …”

That was when I noticed that Marie had hardly touched her poularde Mancini, even though it was her

favorite dish. Had love taken away her appetite? And my father was growing impatient because Henri, carried away by his thoughts, hadn’t realized that the butler was waiting stoically to his left, presenting him with a dish as hot as it was heavy.

“… and he says it’s rooted in the proscription against masturbation.”

“Fancy that!” exclaimed my father, whose relief at seeing Henri serve himself at last probably sounded like sincere interest in the conversation. Henri, in any case, was warming to his theme.

“Aristotle affirms that melancholy is the affliction of the superior man. And to be melancholy, in those days, meant being inactive, meditative, sad, humble, and therefore of superior intelligence, since hyperactive people were rarely geniuses.”

Failing to pickup my father’s desperate glances around the table in a mute appeal for help, Henri charged ahead.

“Moreover, when you take a look at history, boredom has always been on the winning side, from tedious old Louis XI, called the Prudent, who triumphed over the warrior Charles the Bold, to the Catholic faith, which had a troubled relationship to boredom and idleness, so conducive to impure thoughts and actions—although

this didn’t prevent the church from inventing the convent, a whole universe of boredom!”

Gay was probably thinking up a way to stop Henri in midflight as she sat delicately cutting her mimolette and Gouda with cumin into tiny cubes, as she did every evening, before popping them in her mouth …

“Of course, everything changed when the Anglo-Saxon—and therefore Protestant—model took over the world, and the notion of leisure (etymologically, that means

licit

, in other words, permitted) replaced that of vacation (derived from the concept of vacancy) …”

… because with a definite wink at my father, she abruptly broke in: “Speaking of vacations, my dear Henri, have you any plans for the rest of the summer?”

Turning back to Marie, I saw that she seemed strained, so closely was she watching Béno in hopes of catching a glimmer of interest in his eyes, but like everyone else, he was probably more captivated by the soufflé, and the way the piping-hot apples, like lava from a volcano, overflowed from the core of ice cream perfumed with flecks of vanilla that crunched between our teeth.

“I adore desserts that combine hot and cold things, don’t you?” asked Marie.

“Yes, absolutely,” agreed Frédéric. “Let’s see, what others are there? Ah! There’s the Norwegian omelet,

crêpes

royale …”

Then I understood that something clearly wasn’t right. Because Béno, who should have smiled at Marie when she spoke up, had kept his nose in his dessert, as if avoiding meeting her eyes. I didn’t have time to get any further with this, however, because we were all leaving the table.

I was going over to Marie to make her tell me what was going on when Béno stepped in front of our mother.