The Storyteller (15 page)

Authors: Walter Benjamin

So has from the little German village canton up to that of the Javanese primal forest every form on earth buried its physiognomic seal in the writings of German geographers, travellers and poets in one century. Therefore the title of this book is more than a happy formulation: a discovery, and each reader will find fulfilled in it the hope of its editor, which is âto introduce' a portion of âlost German intellectual greats'.

â

Translated by Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski

.

First published in the

Frankfurter Zeitung

, 3 February 1928;

Gesammelte Schriften III

, 88â94.

Review: Collection of

Frankfurt Children's Rhymes

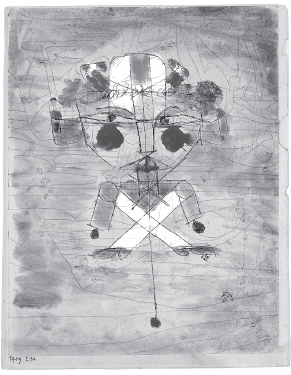

Bust of a Child (Kopf eines Kindes)

, 1939.

T

he cultural effect that children's lives and activities exert on the ethnic and linguistic communities in which they take place has been, to this day, a largely unexplored chapter of cultural history, and yet it is one of the most relevant. As contribution to this, the highest value should be accorded to a comprehensive collection of verses and sayings of children from Frankfurt, of which I am about to convey something. Its creator is the locally based Rector Wehrhan, though incidentally he is

not a child of Frankfurt but, rather, a native of Lippe. In 1908, he laid the foundations for a large archive, which has grown over the course of time to include well over a thousand pieces and fragments, thanks not only to his tireless efforts, but also to a well-organised support system. Everything â all manner of verses, turns of phrase, jokes and puzzles â that accompanies the lives of Frankfurt schoolchildren, from their earliest babyhood to the threshold of puberty, can be found here, no matter whether these are the child's own idioms or whether they have their origin in stereotypical phrases from their parents' tongue.

What is found in Wehrhan's collection, however, is partly an ancient good; in only a few cases was it created by children. And the judicious user of these documents will not focus on âoriginals'. Rather, here he can trace how the child âmodels', how he or she âtinkers', how â in the intellectual realm as well as in the sensuous one â he or she never adopts the established form as such, and how the whole richness of his or her mental world occupies the narrow track of variation. The children return the oldest fragments and phrases of verse to the adults in variegated forms; their work lies not so much in the gist of these pieces, as in the unpredictably appealing play of transformation. The material encompasses around a hundred folders, organised according to keywords. There are âthe first jokes', âbaking cakes', ârhymes told on the lap', âgoing to bed and getting up', âthe dumb and clumsy child', âthe weather', âanimal names', âplants', âweekdays', âZeppelin', âworld war', ânicknames', âJewish rhymes', âbanter and teasing', âtongue twisters', âpopular songs', to name but a few. This is to say nothing of the great collection of playground rhymes and the impressive codex of hopscotch games, including the copious schemes that have been drawn in chalk onto the pavements of Frankfurt, where, over the years, playing children have hopped on one leg.

Some rhymes from the World War with their scathing satirical power:

My mother became a soldier

She got some trousers for that

With red edging

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

She received a coat for that

With shiny buttons on it

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

She got some boots for that

With high legs on them

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

She received a helmet for that

With Kaiser Wilhelm on it

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

She got a shotgun for that

And so she shoots here and there

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

So then she went into the trenches

And there she got kohlrabi

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

My mother became a soldier

She got put in a military hospital

She got put in a canopy bed

Tara zing da

My mother became a soldier.

If I stand in the dark midnight

So lonely on the hunt for lice

And I think of my silent home

That thinks of me in the moonlight.

Little Marie

You silly little cow

I will pull up one of your little legs

Then you must limp

On your ham

Then you will go to the city hospital

Then you'll be operated on

You will be smeared with soft soap

Then the German men's choir will come

And sing a little song for you.

Some counting rhymes:

On a rubber-rubber-mountain,

There lives a rubber-rubber-dwarf,

Has a rubber-rubber-wife.

The rubber-rubber-wife

Has a rubber-rubber-child.

The rubber-rubber-child

Has a rubber-rubber-ball,

Threw it in the air.

The rubber-rubber-ball

Broke.

And you are a Jew.

* Â Â Â Â Â * Â Â Â Â Â *

10, 20, 30,

Girl, you work hard,

40, 50, 60,

Girl, you are blotchy,

70, 80, 90,

Girl, you are alone.

Some constructivist feats:

Last glove I lost my autumn.

I went finding for three days, before I looked for it.

I came to a peep, there I peered through.

There sat three chairs on a man.

Now I took off my good day and said:

âHat, Sirs'.

Lovely father from my greeting. Here would be

Soles to beboot. He does not need to money for his fear.

If he would come in, he would pass by.

An old cloister joke from children's lips:

Dear parish of Pig Mountain!

Stand up or remain seated.

We read in the book of Pitchfork,

Six prongs and thirty-five gaiter buttons,

Where it is written:

In my earliest youth I perpetrated my boldest deed.

With ice-cold water I burnt out the eyes of children.

And with a blunt rasp I cut off their fingers.

After the deed was done the broom handle arrested me.

This brought me to the higher regional court Burglary.

Here I received fourteen days detention, afterwards freedom.

Now receive the blessing of the Lord!

The hat-maker makes hats for you,

The umbrella-maker makes covers for you,

The roof-maker lets his roofs shine over you.

We are singing song number three hundred:

Big clump, we plane you!

Hallelujah!

Hopefully all those who are interested in researching children's creativity need not wait too long for a complete publication of the Wehrhan collection.

â

Translated by Esther Leslie

.

First published

Frankfurter Zeitung

, 16 August 1925;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 792â6.

Fantasy Sentences

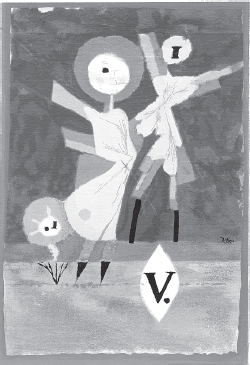

Portrait Sketch of a Costumed Lady (Bildnisskizze einer kostümierten Dame)

, 1924.

F

ormed by an eleven-year-old girl from words given to her.

Freedom â garden â faded â greeting â crazy â eye of a needle

Since freedom cannot be attained as quickly as the leaves in the garden have faded, its greeting is all the stormier, and even the crazy people, who believe the eye of a needle to be larger than a monkey, take part.

Table cloth â sky â pillow â continent â eternity

The table in front of him was covered by a table cloth and it stood under the open sky. He lay on the pillow on the continent remote from the world, as if he did not want to wake up for eternity.

Lips â bendy â dice â rope â lemon

Her lips were so rosy, like bendy roses, when one infected them while playing with dice or during a tug of war with a rope, but her gaze was bitter like the peel of a lemon.

Corner â emphasis â character â drawer â flat

On the corner â he said it with emphasis â I saw a character that was flat like a drawer.

Pipe â border â booty â busy â skinny

The pipe at the border was a place for robbers. This is where they brought their booty, since the path was not busy. In the moonlight, the figures appeared skinny.

Pretzel â feather

1

â pause â lament â doohickey

Time curves like a pretzel through nature. The feather paints the landscape and, if there is a pause, then it is filled with rain. One hears a lament because there is no doohickey.

â

Translated by Esther Leslie

.

First published in

Die Literarische Welt

, 3 December 1926;

Gesammelte Schriften IV

, 802â3.

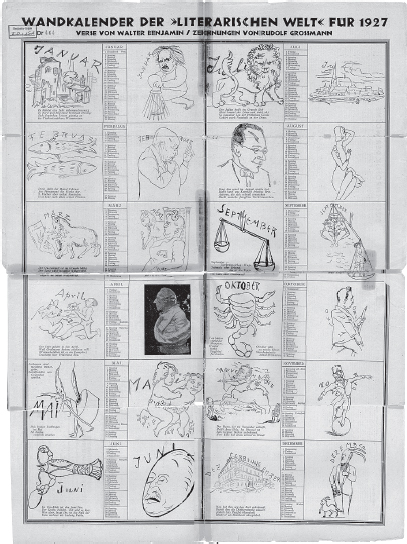

Wall Calendar from

Die

literarische Welt

for 1927

Flower Family V (Blumenfamilie V)

, 1922.

Wall calendar from

Die literarische Welt

, 1927, from which these verses were taken

Verses by Walter Benjamin Drawings by Rudolf Grossmann

JANUARY

The year 1927 is announced

In tones to be heard in North and South

(and in Free City Danzig).

For German readers of this almanac

Aquarius is the sign of the zodiac.

1

FEBRUARY

Next the month of February

Presents the fishes' canopy.

S. Fischer though lives here on earth

And offers you his peace for all it is worth.

2

MARCH

The

Querschnitt

mag is cheap basically,

Springtime

3

creeps up only reluctantly.

To the joy of every good snob

Both are ruled by Wedderkop.

4

APRIL

April is the month of the bull,

But Grossmann won't draw one at all.

(Probably a result of some complex)

So here instead is Fridericus Rex.

5

MAY

Laurels are usually evergreens,

Writers squirt out thoughts as streams.

For the twins in May

It doesn't matter either way.

JUNE

The June animal, beloved of the Pen-Club member,

Is right here â the crab â on the agenda.

But who, you might ask, is that nought?

It is Ludwig Fulda and none ought.

6

JULY

Bab is essentially the name of July

(the lion growls and says bye-bye).

Many a lion with polemics to deliver

Belongs to Neustadt on the Dosse River.

7

AUGUST

Prague, which usually in August is bare,

Today bakes fresh bread from cornfields there â

Authors who all too quickly give in

Result from the sign of the zodiac which is the virgin.

8

SEPTEMBER

September â

Libra or scale is the astrological sign

The question being â

Filth or grime,

Let us weigh it up quite precisely

Lulu or Gneisenau â which will it be?

9

OCTOBER

Scorpio stings from his rump

Head-on, Siegfried Jacobsohn delivered his thump.

October lets us him revere

With Sternheim's astral-premieres.

10

NOVEMBER

The man in November with arrow and bow,

is called Arno Holz. Heaven does not know

Becker, who is his rival.

Herr Külz has a tricky pedestal.

11

DECEMBER

Quite badly crumpled is his beard,

Through which the purrs of the poet are heard,

Still (if as pacifist, he is inadmissible)

He remains, as a Capricorn, quite permissible.

â

Translated by Esther Leslie

.

First published in

Die literarische Welt

, 24 December 1926;

Gesammelte Schriften VI

, 545â7.