The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (17 page)

Marius had been preparing for this war, and hoped to be the general; but, to his great disappointment, the command was given to his rival, Sulla. The army had no sooner started than the envious Marius began to do all he could to have Sulla recalled. His efforts were successful, for the Romans soon sent orders for Sulla to come home, and gave the command of the army to Marius instead.

When the officers came to tell Sulla that he must give up his position, he was so angry that he had the messengers put to death. Then, as his soldiers were devoted to him, they all asked him to lead them back to Rome, so that they might punish his enemies for slandering him behind his back.

This change of programme suited Sulla very well. Instead of going to Asia, he soon entered Rome, sword in hand, routed Marius and his party, and, after forcing them to seek safety in flight, took the lead in all public affairs.

Marius was declared an enemy of his country, and closely pursued by some of Sulla's friends. Although seventy years of age, he fled alone and on foot, and made his way down to the seashore. He then tried to escape on a vessel which he found there; but, unfortunately, the captain was a mean man, who, in fear of punishment, soon set Marius ashore and sailed away. The aged fugitive was then obliged to hide in the marshes; and for a long time he stood there buried in a quagmire up to his chin. Finally he was captured, and fell into the hands of the governor of Minturnæ.

Marius, the man who had enjoyed two triumphs, and had six times been consul of Rome, was now thrust into a dark and damp prison. A slave—one of the vanquished Cimbri—was then sent to his cell to cut off his head. But when the man entered, the prisoner proudly drew himself up, and, with flashing eye, asked him whether he dared lay hands upon Marius.

Terrified by the gaunt and fierce old man, the slave fled, leaving the prison door open. The governor, who was very superstitious, now said it was clear that the gods did not wish Marius to perish; so he not only set the prisoner free, but helped him find a vessel which would take him to Carthage.

There, amid the ruins of that once mighty city, the aged Marius sat mourning his fate, until ordered away by the Roman guard, a man whom he had once befriended. Again Marius embarked, to go in search of another place of refuge; but, hearing that Cinna, one of his friends, had taken advantage of Sulla's absence from Rome to rally his party, he decided to return at once to Italy.

The Proscription Lists

M

ARIUS

would not reenter Rome until the frightened senate recalled his sentence of banishment; for he always appeared very anxious to obey the laws, so as to make the people believe that he was thinking only of them.

The Roman citizens were, therefore, called together, the question was put to the vote, and Marius found a large majority in favor of his return. He entered Rome, as powerful as ever, and celebrated his return by ordering the death of all the people who had been his enemies.

Marius and Cinna named themselves consuls, and one of their first acts was to set aside all the laws made by Sulla. Their next was to hunt up all his friends, and to carry out their bloody plans for revenge by killing them all. Fortunately for the Romans, however, the old man died one month after his return to Rome, and thus his bloody career came to an end.

In the mean while the news that Marius had returned to Rome was sent as quickly as possible to Sulla, who was making war against Mithridates in the East. Sulla waited till he had won many victories over this king; then, making peace, he came home as fast as possible to punish the men who had murdered his friends.

It was too late to injure Marius, for he was dead; but Sulla was fully as bloodthirsty as his former rival, and turned his wrath against Cinna and the son of Marius, who were now at the head of their party. Hearing that Sulla had made peace with Mithridates, and was on his way home, Cinna sent an army to meet and stop him.

But, instead of fighting Sulla, the Romans deserted, and joined him, hoping to receive a share of the gold which he had brought back from the East. Owing to this increase in his forces, and to the help of Pompey, who raised an army for him in Italy, Sulla won several victories, and finally marched into Rome at the head of his troops.

Cinna was killed by his own soldiers, and when Sulla entered Rome he had eight thousand prisoners of war who had belonged to the party of Marius. Instead of showing himself generous, he secretly ordered the massacre of all these men before he went to the senate.

The cries and groans of the dying could be plainly heard by the senators. They trembled and grew pale, but they did not dare oppose Sulla, and only shuddered when he said: "I will not spare a single man who has borne arms against me."

Then, for many days, long lists were made, containing the names of all the citizens whom Sulla wished to have slain. These lists were posted in public places, and a proclamation was made, offering a reward for the killing of each man whose name was marked there, and threatening with death any one—even a relative—who should give such a man shelter.

Through the civil wars waged between the parties of Marius and Sulla, and through these fatal lists, more than one hundred and fifty thousand Roman citizens lost their lives.

Sulla, to prevent any one else from ruling the Romans, now forced them to name him dictator for life. But, after governing for a short time with capricious tyranny, he suddenly gave up his power, and retired to a country house, where he spent his days and nights in revelry of all kinds.

Soon after, he was seized by a most horrible and loathsome disease, which could not be cured. He died, in a terrible fit of senseless anger, after giving orders for his own funeral, and for the building of a magnificent tomb on the Field of Mars. On this was placed the following epitaph, which he had himself composed:

"I am Sulla the Fortunate, who, in the course of my life, have surpassed both friends and enemies; the former by the good, the latter by the evil, I have done them."

But, although Sulla boastfully called himself "the Fortunate," he was never really happy, because he thought more of himself than of his country and fellow-citizens.

Sertorius and His Doe

W

HEN

Sulla died, there were still two parties, or factions, in Rome, which could not agree to keep the peace. These two factions were headed by Catulus and Lepidus, the consuls for that year. Catulus had been a friend of Sulla, and was upheld by Pompey, who was a very clever man. Pompey was not cruel like Marius and Sulla, but he could not be trusted, for he did not always tell the truth, nor was he careful to keep his promises.

As the two consuls had very different ideas, and were at the head of hostile parties, they soon quarreled and came to open war. Catulus, helped by so able a general as Pompey, won the victory, and drove Lepidus to Sardinia, where he died.

Although the civil war at home was now stopped, there was no peace yet, for it still raged abroad. Sertorius, one of the friends of Marius, had taken refuge in Spain when Sulla returned. Here he won the respect and affection of the Spaniards, who even intrusted their sons to his care, asking him to have them educated in the Roman way.

The Spaniards, who were a very credulous people, thought that Sertorius was a favorite of the gods, because he was followed wherever he went by a snow-white doe, an animal held sacred to the goddess Diana. This doe wandered in and out of the camp at will, and the soldiers fancied that it brought messages from the gods; so they were careful to do it no harm.

As the Spaniards shared this belief, they were always ready to do whatever Sertorius bade them; and when a Roman army was sent to Spain to conquer him, they rallied around him in great numbers.

Now you must know that Spain is a very mountainous country. The inhabitants, of course, were familiar with all the roads and paths, and therefore they had a great advantage over the Roman legions, who were accustomed to fight on plains, where they could draw themselves up in battle array.

Instead of meeting the Romans in a pitched battle, Sertorius had his Spaniards worry them in skirmishes. By his orders, they took up their station on the mountains, and behind trees, from whence they could hurl rocks and arrows down upon their foe.

When the Roman general saw that his army was rapidly growing less, and that he would have no chance to show his skill in a great battle, he made a proclamation, offering a large sum of money to any one who would kill Sertorius, and bring his head into the Roman camp.

Sertorius was indignant when he heard of this proclamation, and gladly accepted the offer of Mithridates to join forces with him against the Romans. But before this king could help him, Sertorius grew suspicious of the Spaniards, and fancied that they were about to turn traitors and sell him to the Romans.

Without waiting to find out whether these suspicions were true, he ordered the massacre of all the boys intrusted to his care. Of course the Spaniards were furious, and they all declared that it served Sertorius right when Perperna, one of his own men, fell upon him while he was sitting at table, and killed him.

In the mean while, however, the Roman senate had sent out another army, under Pompey, and this general had fought several regular battles with Sertorius. Perperna now tried to take the lead of the Spaniards and the Romans who hated Pompey; but, as he was a coward, he lost the next battle and was made prisoner. Hoping to save his life, Perperna then offered to hand over all the papers belonging to Sertorius, so that Pompey could find out the names of the Romans who were against him.

Fortunately, Pompey was too honorable to read letters which were not addressed to him. Although he took the papers, it was only to fling them straight into the fire without a single glance at their contents. Then he ordered that Perperna, the traitor, should be put to death; and, having ended the war in Spain, he returned to Rome.

The Revolt of the Slaves

P

OMPEY'S

services were sorely needed at home at this time, and it was fortunate that the war in Spain was near its end. The cause of the trouble in Italy was a general revolt of the slaves.

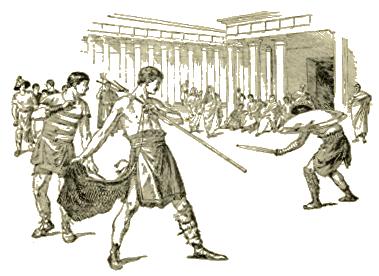

It seems that at Capua, in southern Italy, there was a famous school of gladiators. Now, as you doubtless remember, the gladiators were prisoners of war whom the Romans trained to fight in the circuses for their amusement.

Spartacus, a Thracian, was the leader of these men; and, when they broke away from their captivity, he led them to Mount Vesuvius, where they were soon joined by many other gladiators and runaway slaves. In this position they could easily defend themselves, and from Mount Vesuvius they made many a raid down into the surrounding country, in search of provisions and spoil.

Roman Gladiators

Little by little, all the Thracian, Gallic, and Teutonic slaves joined them here, and before long Spartacus found himself at the head of an army of more than a hundred thousand men. Many legions were sent out to conquer them; but the slaves were so eager to keep their liberty that they fought very well, and defeated the Romans again and again.

Spartacus, having tried his men, now prepared to lead them across Italy to the Alps, where he proposed that they should scatter and all rejoin their native tribes. But this plan did not meet with the approval of the slaves; for they were anxious to avenge their injuries, and to secure much booty before they returned home.

So, although Spartacus led them nearly to the foot of the Alps, they induced him to turn southward once more, and said that they were going to besiege Rome. In their fear of the approaching rebels, the Romans bade Crassus, one of Sulla's officers, take a large army, and check the advance of the slaves. At the same time, they sent Pompey an urgent summons to hasten his return from Spain.

The armies of Crassus and Spartacus met face to face, after many of the slaves had deserted their leader. The Thracian must have felt that he would be defeated; for he is said to have killed his war horse just before the battle began. When one of his companions asked him why he did so, he replied:

"If I win the fight, I shall have a great many better horses; if I lose it, I shall need none."

Although wounded in one leg at the beginning of the battle, Spartacus fought bravely on his knees, until he fell lifeless upon the heap of soldiers whom he had slain. Forty thousand of his men perished with him, and the rest fled. Before these could reach a place of safety, they were overtaken by Pompey, who cut them all to pieces.

Pompey had come up just in time to win the last battle, and reap all the honors of the war. He was very proud of this victory, and wrote a boastful letter to the senate, in which he said: "Crassus has overcome the gladiators in a pitched battle, but I have plucked up the war by the roots!"

Then, to make an example which would prevent the slaves from ever rising up against their masters again, the Romans crucified six thousand of the rebels along the road from Capua to Rome.