The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (11 page)

Camillus made his men dig an underground passage right into the heart of the enemy's citadel. Having thus gained an entrance, he captured or slew all the inhabitants, and then razed the walls that had so long defended them. When he returned to Rome, he was rewarded by a magnificent triumph.

The School-Teacher Punished

T

HE

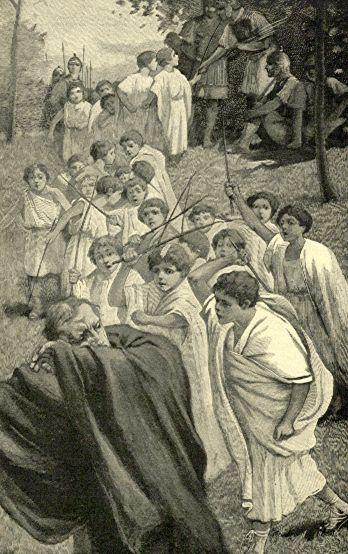

war with Veii was soon followed by one against the city of Falerii, and here too the Roman army found it very hard to get possession of the town. One day, however, a school-teacher came to Camillus, bringing his pupils, who were the sons of the principal inhabitants of Falerii.

Camillus was surprised to see the strange party coming from the city, but his surprise was soon changed to indignation, for the faithless schoolmaster offered to give up the children confided to his care. He said that their parents would be quite ready to make peace on any terms, as soon as they found that their sons were prisoners. Instead of accepting this proposal, Camillus sent the children back to their parents; and he gave each of them a whip with directions to whip the dishonest schoolmaster back into the city.

The School-Teacher Punished

When the parents heard that their children owed their liberty to the generosity of the enemy, they were deeply touched. Instead of continuing the war, they offered to surrender; and Camillus not only accepted their terms, but made them allies of Rome. Thus a second war was ended by his efforts, and the Romans were again victorious.

In spite of his successes abroad, Camillus was not a favorite at home. Shortly after his return from this last campaign, the Romans, who disliked him, accused him of having kept part of the spoil which had been taken at Veii.

This accusation was false; but, in spite of the protests of Camillus, they persisted in repeating it, and finally summoned him to appear before the magistrates, where he would be tried. This was very insulting, but Camillus would have complied had there been any hope of having an honest trial.

As all those who were to judge him were his enemies, he refused to appear before the court, and preferred to leave his city and go off into exile. But when he passed out of the gates, he could not restrain his indignation. Raising his hands to heaven, he prayed that his countrymen might be punished for their ingratitude.

This prayer was soon answered. Not long after Camillus had left Rome, the Gauls, a barbarous people from the north, came sweeping down into Italy, under the leadership of their chief, Brennus.

These barbarians were tall and fierce; they robbed and killed with ruthless energy wherever they went, and, in spite of every obstacle, they swept onward like a devastating torrent. Before the Romans could take any steps to hinder it, they appeared before the city of Clusium, and laid siege to it.

The Clusians were the friends and allies of the Romans, and the latter sent three ambassadors of the Fabian family to command the Gauls to retreat. Brennus received them scornfully, and paid no heed to their commands.

Now it was the duty of the Fabii, as ambassadors, to return to Rome and remain neutral. Instead of this, the men sent a message to Rome, joined the Clusians, and began to fight against the Gauls.

Although he was only a barbarian, Brennus was furious at this lack of fairness. In his anger he left the city of Clusium, and started out for Rome, saying that he would make the Romans pay the penalty for the mistake of their ambassadors.

The Invasion of the Gauls

A

HASTILY

collected army met Brennus near the river Allia, but in spite of the almost superhuman efforts of the Romans, the Gauls won a great victory, and killed nearly forty thousand men. The Roman army was cut to pieces, and no obstacle now prevented the barbarians from reaching Rome.

As the Gauls advanced, the people fled, while many soldiers took refuge in the Capitol, resolved to hold out to the very last. The rest of the city was deserted, but seventy of the priests and senators remained at their posts, hoping that the sacrifice of their lives would disarm the anger of their gods, and save their beloved city. These brave men put on their robes of state, and sat in their ivory chairs on the Forum, to await the arrival of the barbarians.

When the Gauls reached the city, they were amazed to find the gates wide open, the streets deserted, and the houses empty. They did not at first dare enter, lest they should be drawn into an ambush, but, reassured by the silence, they finally ventured in. As they passed along the streets, they gazed with admiration at the beautiful buildings.

At last they came to the Forum, and here they again paused in wonder in front of those dignified old men, sitting silent and motionless in their chairs. The sight was so impressive that they were filled with awe, and began to ask whether these were living men or only statues.

One of the Gauls, wishing to find out by sense of touch whether they were real, slowly stretched out his hand and stroked the beard of the priest nearest him. This rude touch was considered an insult by the Roman, so he raised his wand of office, and struck the barbarian on the head.

The spell of awe was broken. The Gaul was indignant at receiving a blow, however weak and harmless, and with one stroke of his sword he cut off the head of the offender. This was the signal for a general massacre. The priests and senators were all slain, and then the plundering began.

When all the houses and temples had been ransacked, and their precious contents either carried off or destroyed, the barbarians set fire to the city, which was soon a mass of ruins. This fire took place in the year 390

B

.

C

.

, and in it perished many records of the early history of Rome. Because of their loss, not much reliable information was left; but the Romans little by little put together the history which you have heard in the preceding chapters.

We now know that many of these stories cannot be true, and that the rest are not entirely so. And this is the case also with those in the next two or three chapters; for the first historians did not begin to write till many years after the burning of Rome. The Romans, however, believed thoroughly in all these stories, and people nowadays need to know them as much as the perfectly true ones that follow.

The Sacred Geese

R

OME

was all destroyed except the Capitol, where the little army was intrenched behind the massive walls which had been built with such care by Tarquin. This fortress, as you may remember, was situated on the top of the Capitoline hill, so that the Gauls could not easily become masters of it.

Whenever they tried to scale the steep mountain side, the Romans showered arrows and stones down upon them; and day after day the Gauls remained in their camp at the foot of the Capitol, hoping to starve the Romans into surrender.

The garrison understood that this was the plan which Brennus had made; so, to convince him that it was vain, they threw loaves of bread down into his camp. When the chief of the Gauls saw these strange missiles, he began to doubt the success of his plan; for if the Romans could use bread as stones, they were still far from the point of dying of hunger.

One night, however, a sentinel in the Gallic camp saw a barefooted Roman soldier climbing noiselessly down the steep rock on which the Capitol was built. The man had gone to carry a message to the fugitives from Rome, asking them to come to the army's relief.

The sentinel at once reported to Brennus what he had seen; and the Gallic chief resolved to make a bold attempt to surprise the Romans on the next night. While the weary garrison were sound asleep, the Gauls silently scaled the rocks, following the course which the Roman soldier had taken in coming down.

The barbarians were just climbing over the wall, when an accidental clanking of their armor awoke the sacred geese which were kept in the Capitol. The startled fowls began cackling so loudly that they roused a Roman soldier named Manlius.

As this man glanced toward the wall, he saw the tall form of a barbarian looming up against the sky. To spring forward, and hurl the Gaul down headlong, was but the work of a moment. The man, in falling, struck his companions, whose foothold was anything but secure, and all the Gauls rolled to the foot of the rock, as Manlius gave the alarm.

All hope of surprising the Capitol was now at an end, so Brennus offered to leave Rome, on condition that the senate would give him one thousand pounds of gold. This was a heavy price to pay for a ruined city, but the Romans agreed to give it.

When they brought the precious metal and began to weigh it, they found that the barbarians had placed false weights in the scales, so as to obtain more gold than they were entitled to receive. The Romans complained; but Brennus, instead of listening to them, flung his sword also into the scales, saying, scornfully, "Woe to the vanquished!"

While the Romans stood there hesitating, not knowing what to do, the exiled Camillus entered the city with an army, and came to their aid. When he heard the insolent demands of the barbarians, he bade the senators take back the gold, and proudly exclaimed:

"Rome ransoms itself with the sword, and not with gold!"

Next, he challenged Brennus to fight, and a battle soon took place in which the Gauls were defeated with great slaughter, and driven out of the country. As soon as they were fairly gone, the fugitive Romans began to return, and many were the laments when they beheld their ruined homes.

Instead of wasting time in useless tears, however, they soon set to work to rebuild their dwellings from the stones found in the ruins; and as each citizen placed his house wherever he pleased, the result was very irregular and unsightly.

Manlius, the soldier who saved the Capitol from the barbarians, was rewarded by being given the surname of Capitolinus, and a house and pension. He was so proud of these honors, however, that he soon wanted to become king of Rome. He formed a plot to obtain possession of the city, but this was discovered before it could be carried out.

Manlius Capitolinus was therefore accused of treachery, and arrested. He was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to death. Like any other traitor, he was flung from the top of the Tarpeian Rock, and thus he perished at the foot of the mountain which he had once saved from the assault of the Gauls.

Two Heroes of Rome

N

OT

very long after the departure of the Gauls, and the tragic end of Manlius Capitolinus, the Romans were terrified to see a great gap or chasm in the middle of the Forum. This hole was so deep that the bottom could not be seen; and although the Romans made great efforts to fill it up, all their work seemed to be in vain.

In their distress, the people went to consult their priests, as usual, and after many ceremonies, the augurs told them that the chasm would close only when the most precious thing in Rome had been cast into its depths.

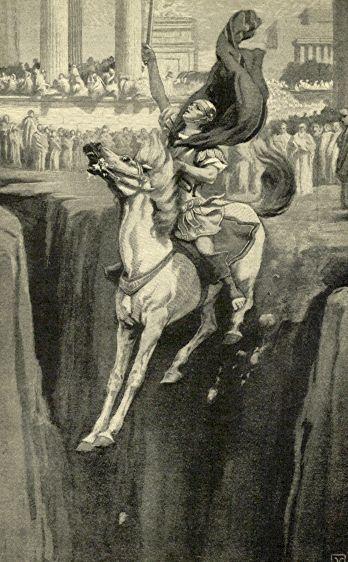

The women now flung in their trinkets and jewels, but the chasm remained as wide as ever. Finally, a young man named Curtius said that Rome's most precious possession was her heroic men; and, for the good of the city, he prepared to sacrifice himself.

Clad in full armor, and mounted upon a fiery steed, he rode gallantly into the Forum. Then, in the presence of the assembled people, he drove the spurs deep into his horse's sides, and leaped into the chasm, which closed after him, swallowing him up forever.

Curtius leaping into the Chasm

Now while it is hardly probable that this story is at all true, the Romans always told it to their children, and Curtius was always held up as an example of great patriotism. The place where he was said to have vanished was swampy for a while, and was named the Curtian Lake; and even after it had been drained, it still bore this name.

The same year that Curtius sacrificed himself for the good of the people, Camillus also died. He was regretted by all his fellow-citizens, who called him the second founder of Rome, because he had encouraged the people to rebuild the city after the Gauls had burned it to the ground.