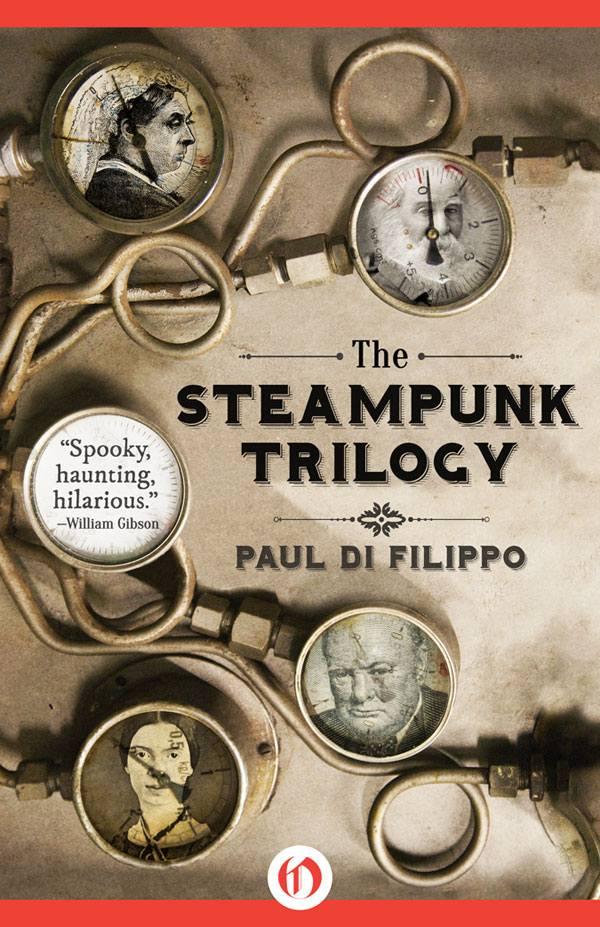

The Steampunk Trilogy

Read The Steampunk Trilogy Online

Authors: Paul Di Filippo

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General

Paul Di Filippo

To my very own Newt(on)

CONTENTS

3.

THE MAN WITH THE SILVER NOSE

6.

TREACHERY AT CARKING FARDELS

1.

“MORNING MEANS JUST RISK—TO THE LOVER”

2.

“DEATH IS THE SUPPLE SUITOR”

3.

“THE SOUL SELECTS HER OWN SOCIETY”

5.

“MICROSCOPES ARE PRUDENT IN AN EMERGENCY”

6.

“BY WHAT MYSTIC MOORING SHE IS HELD TODAY”

7.

“HOPE IS THE THING WITH FEATHERS”

8.

“THE SPIRIT LOOKS DOWN ON THE DUST”

10.

“DROPPED INTO THE ETHER ACRE—WEARING THE SOD GOWN”

11.

“THE GRASS SO LITTLE HAS TO DO, I WISH I WERE A HAY”

12.

“HOW ODD THE GIRL’S LIFE LOOKS BEHIND THIS SOFT ECLIPSE”

13.

“THERE WAS A LITTLE FIGURE PLUMP FOR EVERY LITTLE KNOLL”

VICTORIA

“I was tired, so I slipped away.”

—Queen Victoria, in her private journal.

1

POLITICS AT MIDNIGHT

A

ROD OF

burnished copper, affixed by a laboratory vise-grip, rose from the corner of the claw-footed desk, which was topped with the finest Moroccan leather. At the height of fifteen inches the rod terminated in a gimbaled joint which allowed a second extension full freedom of movement in nearly a complete sphere of space. A third length of rod, mated to the first two with a second joint, ended in a fitting shaped to accommodate a writer’s grip: four finger grooves and a thumb recess. Projecting from this fitting was a fountain-pen nib.

The flickering, hissing gas lights of the comfortable secluded picture-hung study gleamed along the length of this contraption, giving the mechanism a lambent, buttery glow. Beyond rich draperies adorning the large study windows, a hint of cholera-laden London fog could be detected, thick swirls coiling and looping like Byzantine plots. The sad, lonely clopping of a brace of horses pulling the final late omnibus of the Wimbledon, Merton and Tooting line dimly penetrated the study, reinforcing its sense of pleasant seclusion from the world.

Beneath the nib at the end of its long arm of rods was a canted pallet. The pallet rode on an intricate system of toothed tracks mounted atop the desk, and was advanced by a hand-crank on the left. A roll of paper protruded from cast-iron brackets at the head of the pallet. The paper, coming down over the writing surface, was taken up by a roller at the bottom of the pallet. This roller was also activated by the hand-crank, in synchrony with the movement of the pallet across the desk.

In the knee-well of the large desk was a multi-gallon glass jug full of ink, resting on the floor. From the top of the stoppered jug rose an India-rubber hose, which traveled upward into the brass tubing and thence to the nib. A foot-activated pump forced the ink out of the bottle and into the system at an appropriate rate.

Fitted into the center of this elaborate writing mechanism was the ingenious and eccentric engine that drove it.

Cosmo Cowperthwait.

Cowperthwait was a thin young gentleman with a ruddy complexion and sandy hair, a mere twenty-five years old. He was dressed in finery that bespoke a comfortable income. Paisley plastron cravat, embroidered waistcoat, trig trousers.

Pulling a large turnip-watch from his waistcoat pocket, Cowperthwait adjusted its setting to agree with the 11:45 passage of the Tooting omnibus. Restoring the watch to its pocket, he tugged down the naturopathic corset he wore next to his skin. The bulky garment, with its many sewn-in herbal lozenges, had a tendency to ride up from his midriff to just under his armpits.

Now Cowperthwait’s somewhat moony face fell into an expression of complete absorption, as he composed his thoughts prior to transcribing them. Right hand holding the pen at the end of its long arm, left hand gripping the crank, right foot ready to activate the pump, Cowperthwait sought to master the complex emotions attendant upon the latest visit to his Victoria.

Finally he seemed to have sufficiently arrayed his cogitations. Lowering his head, he plunged into his composition. The crank spun, the pump sucked, the pallet inched crabwise across the desk along an algebraic path resembling the Pearl of Sluze, the arm swung to and fro, the paper travelled below the nib, and the ink flowed out into words.

Only by means of this fantastic machinery—which he had been forced to contrive himself—was Cowperthwait able to keep up with the wonted speedy pace of his feverish naturalist’s brain.

May 29, 1838

V. seems happy in her new home, insofar as I am able to ascertain from her limited

—

albeit hauntingly attractive

—

physiognomy and guttural vocables. I am assured by Madame de Mallet that she is not being abused, in terms of the frequency of her male visitors, nor in the nature of their individual attentions.

(

There are other dolly-mops there, more practiced and hardened than my poor V., to whom old de Mallet is careful to conduct the more, shall we say, demanding patrons.

)

In fact, the pitiable thing seems to thrive on the physical attention. She certainly appeared robust and hearty when I checked in on her today, with a fine slick epidermis that seems to draw one’s fascinated touch.

(

Madame de Mallet appears to be following my instructions to the letter, regarding the necessity for keeping V.’s skin continually moist. There was a large atomizer of French manufacture within easy reach, which V. understood how to use.

)

Taking her pulse, I was again astonished at the fragility of her bones. As I bent over her, she laid one hand with those long thin flexible, slightly webbed digits across my brow, and I nearly swooned.

It is for the best, I again acknowledged to myself, to have her out of the house. Best for her, and above all, best for me and the equilibrium of my nerves, not to mention my bodily constitution.

As for her diet, there is now established a steady relationship with a throng of local urchins who, for tuppence apiece daily, are willing to trap the requisite insects. I have also taught them how to skim larval masses from the many pestilential pools of standing water scattered throughout the poorer sections of the city. The boys’ pay is taken from V.’s earnings, although I let it be known that, should her patronage ever slacken, there would be no question of my meeting the expenses connected with her maintenance.

It seems a shame that my experiments had to end in this manner. I had, of course, no way of knowing that the carnal appetites of the Hellbender would prove so insusceptible to restraint, nor her mind so unamenable to education. I feel a transcendent guilt in having ever brought into this world such a monster of nature. My only hope now is that her life will not be overly prolonged. Although as to the proper lifespan of her smaller kin, I am in doubt, as the authorities differ considerably.

God above! First my parents’ demise, and now this, both horrible incidents traceable directly to my lamentable scientific dabblings. Can it be that my honest desire to improve the lot of mankind is in reality only a kind of doomed hubris . . .?

Cowperthwait laid his head down on the pallet and began quietly to sob. He did not often indulge in such self-pity, but the late hour and the events of the day had combined to unman his usual stern scientific stoicism.

His temporary descent into grief was interrupted by a peremptory knock on his study door. Cowperthwait’s attitude altered. He sat up and answered the interruption with manifest irritation.

“Yes, yes, Nails, just come in.”

The door opened and Cowperthwait’s manservant entered.

Nails McGroaty—expatriate American who boasted a personal history out of which a whole mythology could have been composed—was the general factotum of the Cowperthwait household. Stabler, trapdriver, butler, groundskeeper, chef, bodyguard—McGroaty fulfilled all these functions and more, carrying them out with admirable expedience and utility, albeit in a roughshod manner.

Cowperthwait now saw upon McGroaty’s face as he stood in the doorway an expression of unusual reverence. The man rubbed his stubbled jaw nervously with one hand before speaking.

“It’s a visitor for you, ol’ toff.”

“At this unholy hour? Has he a card?”

McGroaty advanced and handed over a pasteboard.

Cowperthwait could hardly believe his eyes. The token announced William Lamb, Second Viscount Melbourne.

The Prime Minister. And, if the scandalous gossip currently burning up London could be credited, the lover of England’s pretty nineteen-year-old Queen, on the throne just this past year. At this particular point in time, he was perhaps the most powerful man in the Empire.

“Did he say what he wanted?”

“Nope.”

“Well, for Linnaeus’s sake, don’t just stand there, show him in.”

McGroaty made to do so. At the door, he paused.

“I done et supper a dog’s age ago already, figgerin’ as how you wouldn’t take kindly to bein’ disturbed. But I left some for you. It’s an eel-pie. Not as tasty as what I could’ve cobbled up if’n I had some fresh rattler, but not half bad.”

Then he was gone. Cowperthwait shook his head with amusement. The man was hardly civilized. But loyal as a dog.

In a moment, Viscount Melbourne, Prime Minister of an Empire that stretched nearly around the globe, from Vancouver to Hyderabad, stood shaking hands with a baffled Cowperthwait.

At age fifty-nine, Melbourne was still possessed of dazzling good looks. Among those numerous women whose company he enjoyed, his eyes and the set of his head were particularly admired. His social talents were exceptional, his wit odd and mordant.

Despite all these virtues and his worldly successes, Melbourne was not a happy man. In fact, Cowperthwait was immediately struck by the famous Melbourne Melancholia. He knew the source well enough, as did all of London.

Against the wishes of his family, Melbourne had married the lovely, eccentric and willful Lady Caroline Ponsonby, only daughter of Lady Bessborough. Having made herself a public scandal by her unrequited passion for the rake and poet, George Gordon, Lord Byron (to whom she had ironically been introduced by none other than her own mother-in-law, Elizabeth Lamb), she had ultimately provoked Melbourne to the inevitable separation, despite his legendary patience, forbearance and forgiveness. Thereafter, Lady Caroline became so excitable as to be insane, dying ten years ago in 1828. Their son Augustus, an only child, proved feeble-minded and died a year later.

As if this recent scandal were not enough, Melbourne still had to contend against persistent decades-old rumors that his father had in reality been someone other than the First Viscount Melbourne, and hence the son held his title unjustifiably.

Enough tragedy for a lifetime. And yet, Cowperthwait sensed, Melbourne stood on the edge of yet further setbacks, perhaps personal, perhaps political, perhaps a mix of both.

“Please, Prime Minister, won’t you take a seat?”

Melbourne pulled up a baize-bottomed chair and wearily sat. “Between us two, Mister Cowperthwait, with the information I am about to share, there must be as little formality as possible. Therefore, I entreat you to call me William, and I shall call you Cosmo. After all, I knew your father casually, and honored his accomplishments for our country. It’s not as if we were total strangers, you and I, separated by a huge social gap.”

Cowperthwait’s head was spinning. He had no notion of why the P.M. was here, or what he could possibly be about to impart. “By all means—William. Would you care for something to drink?”

“Yes, I think I would.”

Cowperthwait gratefully took the occasion to rise and compose his demeanor. He advanced to a speaking tube protruding from a brass panel set into the wall. He pulled several ivory-handled knobs labeled with various rooms of the house until a bell rang at his end, signaling that McGroaty had been contacted. The last knob pulled had been labeled PRIVY.

The squeaky distant voice of the manservant emerged from the tube. “What’s up, Coz?”

Cowperthwait bit his tongue at this familiarity, repressing a justly merited rebuke. “Would you be so good as to bring us two shandygaffs, Nails.”

“Comin’ up, Guv.”

McGroaty shortly appeared, bearing a tray with the drinks. A bone toothpick protruded from his lips and his shirttails were hanging out. He insouciantly deposited his burden and left.

After they had enjoyed a sip of their beer and ginger-beer mixed drinks, the Prime Minister began to speak.

“I believe, Cosmo, that you are, shall we say, the guardian of a creature known as Victoria, who now resides in a brothel run by Madame de Mallet.”

Cowperthwait began to choke on his drink. Melbourne rose and patted his back until he recovered.

“How—how did you—?”

“Oh, come now, Cosmo, surely you realize that de Mallet’s is patronized by the

bon-ton

,

and that your relationship to the creature could not fail to become public knowledge within a few days of her establishment there.”

“I wasn’t aware—”

“I must say,” Melbourne continued, running a wet finger around the rim of his glass, thereby producing an annoying high-pitched whine, “that the creature provides a novel sensual experience. I thought I had experienced everything the act of copulation had to offer, but I was not prepared for your Victoria. Evidently, I am not alone in appreciating what I take to be her quite mindless skills. In just the past week, I’ve run into many figures of note at de Mallet’s who were there expressly for her services. Those scribblers, Dickens and Tennyson. Louis Napoleon and the American Ambassador. Several of my own Cabinet, including some old buggers I thought totally celibate. Did you know that even that cerebral and artistic gent, John Ruskin, was there? Some friends of his had brought him. It was his first time, and they managed to convince him that all women were as hairless as your Victoria. I predict some trouble should he ever marry.”

“I am not responsible—”

Melbourne ceased to toy with his glass. “Tell me—exactly what is she?”

Having no idea where Melbourne’s talk was leading, Cowperthwait felt relieved to be asked for scientific information. “Credit it or not, William, Victoria is a newt.”

“A newt? As in salamander?”

“Quite. To be precise, a Hellbender,

Cryptobranchus alleganiensis,

a species which flourishes in the New World.”

“I take it she has been, ah, considerably modified. . . .”

“Of course. In my work with native newts, I have succeeded, you see, in purifying what I refer to as a ‘growth factor.’ Distilled from the pituitary, thyroid and endocrine glands, it has the results you see. I decided to apply it to a Hellbender, since they normally attain a size of eighteen inches anyway, and managed to obtain several efts from an agent abroad.”

“And yet she does not look merely like a gigantic newt. The breasts alone. . . .”

“No, her looks are a result of an admixture of newt and human growth factors. Fresh cadavers—”