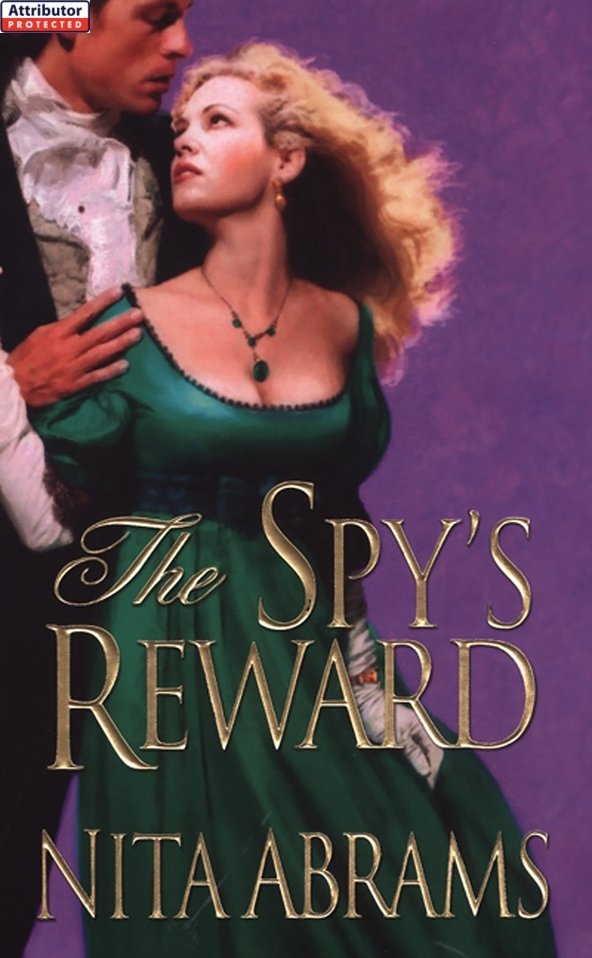

The Spy's Reward

Authors: Nita Abrams

SHE YIELDED

And somehow one moment he was telling himself that he should let Abigail go, should step back, and the next moment he had pulled her straight up against his body and was kissing her so fiercely that he thought he might never breathe again. They were hot, scorching kisses; he was in a fever, he branded her mouth, her throat, her shoulder; he was desperate to take as much as he could in these few minutes.

Her body softened, sank towards him; her face tilted upward. He found himself sitting on the wall; she had tumbled down into his arms, and he was pulling her dress off her shoulder, sliding his hand down the side of her breast. She was not going to stop him, Meyer realized, incredulous.

GREAT BOOKS, GREAT SAVINGS!

When You Visit Our Website:

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

Â

You Can Save 30% Off The Retail Price Of Any Book You Purchase

â¢

All Your Favorite Kensington Authors

All Your Favorite Kensington Authors

â¢

New Releases & Timeless Classics

New Releases & Timeless Classics

â¢

Overnight Shipping Available

Overnight Shipping Available

â¢

All Major Credit Cards Accepted

All Major Credit Cards Accepted

Visit Us Today To Start Saving!

Â

Â

All Orders Are Subject To Availability.

Shipping and Handling Charges Apply.

The

SPY'S R

SPY'S R

EWARD

NITA ABRAMS

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

To JR, Mary, Rachel, Sarah, Will, and Nora:

Poor Abigailâshe has Leah, while I have you

Poor Abigailâshe has Leah, while I have you

P

ROLOGUE

ROLOGUE

London, December 1813

Â

Everyone was wearing black except Abigail. All the Harts, of course: Aaron's widow, Belinda. His brother, Stephen. Stephen's wife, Danielle. Stephen's cousin and business partner, Joshua, who, as the wealthiest of the Harts, was the unofficial head of the family. Even Abigail's own sister was wearing black gloves. Leah was sitting next to Danielle, forming a solid female block of disapproval, and the two of them were explaining the new rules.

“Now that my brother-in-law is dead,” Danielle told her, “things will be considerably less awkward. We believe”âfour severe faces nodded in agreementâ“that it will be acceptable for you to refer to yourself as a widow. Belinda intends to return to her family in Hamburg, and those who knew Aaron well will understand the situation. It is for Diana's sake.”

Diana was wearing black as well, but she was upstairs with Fanny, Abigail's companion. Danielle and Leah did not believe seventeen-year-old females should be present at serious family conferences. Diana had changed dramatically in the nine months since Abigail had last seen her: her daughter had grown up; she was a young lady now instead of a girl pretending to be a young lady. Abigail thought of the havoc that would ensue if Diana's stepmother had charge of her and shuddered. Belinda was a timid, unworldly woman who had barely been able to discipline Diana when Aaron was there to reinforce her. It was obvious the Harts had no confidence in her: Why else was she being sent back to Hamburg when by rights she should be raising her own young son, Diana's half brother? Instead Robert was going to live with Joshua, and the Harts were giving Abigail back her daughter. With certain conditions attached.

“You will go into mourning for at least six months,” Danielle continued. Again there were four nods of agreement. “You will live quietly.” She looked around her, taking in the simple furniture and spare decoration in Abigail's drawing room. “This is not what Diana has been accustomed to, but it is pleasant enough.”

“Would you prefer me to take Diana out of London ?” Abigail tried not to sound too eager.

Joshua cleared his throat. “We thought to keep her here where she could see her father's family regularly, at least at first. But perhaps this summer you might visit one of the watering places. Tunbridge Wells. Or Ramsgate, if you prefer the sea.”

Abigail turned to her sister. “And may she continue to see her grandmother?”

“This has also been discussed.” Leah paused for the inevitable nods. “Mother has agreed to allow Diana to visit, accompanied by me or by Danielle.”

Everyone shifted uncomfortably in their seats. Abigail's mother had not spoken to her since the divorce.

“Now,” said Danielle. “The question of Diana's marriage.” Everyone sat up straight. “Joshua has kindly agreed to take charge of this matter. There is no hurry, of course, but we will all keep our eyes open for suitable prospects. As she will be residing here with you, Abigail, it may happen that you yourself will observe that Diana has a partiality for one or another of the candidates we present to her. Leah and I have persuaded your mother that an arranged marriage of the old-fashioned sort is not appropriate for Diana.”

Abigail suppressed a snort. What they meant was that Diana had been having her own way for years and would likely prove very uncooperative if they attempted anything like the formal, negotiated marriages of Abigail's own generation. Danielle had always been a realist.

“We believe we can trust you to prevent any unacceptable attachments,” Danielle said.

This time there were no nods. Abigail guessed that “we” was Joshua and Danielle. Leah pursed her lips, Stephen frowned, and Belinda looked terrified. There had probably been a ferocious argument on this question. Most members of the Hart family regarded Abigail as the very last person they would choose to advise a young woman on female virtue. She had failed not one but two of the Hart brothers: her first husband, Paul, by letting him die of a mere cold in the chest; her second, Paul's brother Aaron, by insisting on the divorce.

“Naturally, you will tell Joshua immediately of any suitors, welcome or unwelcome, and he will take whatever steps are necessary. After six months, you and Diana may entertain quietly here.” Danielle surveyed the room again. “You may wish to purchase some new furniture; Joshua will reimburse you for any expense.”

“Thank you, but there is no need for him to do so,” Abigail said stiffly.

That was part of the problem, of course. The Harts could have forgiven her for forcing Aaron to divorce her if she had been left poor and helpless. But Abigail Hart was a very wealthy woman. She could refurnish this drawing room twelve times over, and they knew it. When she left Aaron she could have purchased an enormous, elegant home in a fashionable neighborhood. She had chosen instead to buy a small house in Goodman's Fields, which she had furnished to her taste rather than to her pocketbook. Still, she knew that to Diana her home would seem shabby, and she wanted Diana to be comfortable inviting friends here. “I will be glad to assume the expense of redecorating. Perhaps Diana will help me select new things.”

Belinda spoke for the first time. “Diana would like that very much.” Her watery blue eyes met Abigail's and for a moment there was something like friendship between them. Belinda, Abigail was certain, was glad to be a widow.

“Well.” Danielle rose. “It is all settled, then. Belinda, you may fetch Diana down to us.”

There was an awkward silence while Belinda was gone. Then she reappeared, followed by Diana and Fanny.

Danielle beckoned Diana over. “Child, we are leaving. Make your curtsey to Mrs. Asher and to your mother.”

Stiffly, Diana nodded at Fanny. Then, to Abigail's surprise, Diana came over and kissed her quickly on the cheek, darting a quick glance at her two aunts.

“Until Thursday, then.” Danielle herded Diana out the door, and the rest of the party took their leave as quickly as possible. Only Joshua lingered behind. He had always had a certain sympathy for Abigail.

“I hope you are pleased,” he said.

“I am,” she assured him.

“There will be a certain awkwardness at first, but Diana is a lovely girl.”

Fanny said quickly, “Oh, indeed she is!”

Abigail sighed. “Joshua, you can speak plainly with me. She has been indulged and flattered by everyone in that household so outrageously that it is a wonder she behaves as well as she does. She is far too pretty for her own good, and an heiress besides. You may be sure I will keep a close eye on her. I advise you, however, to send Belinda to Germany as quickly as may be, because I predict that Diana will be pleading to return to her care within a week.”

“But Diana was delighted when we proposed this!” He looked around the room, just as Danielle had. “You must think her spoiled indeed if you believe she will care about how big your drawing room is, or how many footmen you have.”

“I certainly hope she is not so petty! No, what she will care about is that I am far stricter than Belinda. Naturally she is eager to come and live with me. She has not been allowed to see me for more than a few hours at a time since she was a little girl. I am forbidden fruit, and you know Diana has always chafed at restrictions of any sort. Right now I represent freedom. After three days here, she will realize that rules in my household do not have exceptions for her.”

“We have every confidence in you.” He bowed to Fanny. “And in Mrs. Asher.”

“Well?” said Fanny eagerly, after the door had closed behind him. “Is it settled?”

“Oh yes. It is all arranged. There are now two widows in this house. I am to wear black, and live quietly, and prevent Diana from forming unsuitable attachments. If I am very, very good, I may be permitted to take Diana to Tunbridge Wells this summer.” She began to laugh, but there was an edge to the laughter, and Fanny's eyes filled with tears.

“But you must be happy? Surely you are happy? I know I am!”

Abigail thought that Fanny's gentle patience would be sorely tried in the months ahead. “Yes,” she said. “I am happy. I would have agreed to almost anything to have her back.”

1

London, February 1815

Â

Eli Roth stopped dead in the doorway of the breakfast room at the sight of the elegant form of his brother-in-law sipping coffee in a chair facing the window. It was half-past seven, and the waxing daylight revealed that Meyer was not only up but dressed for a formal morning callâhis jacket pressed, his neckcloth carefully folded, and a heavy gold ring (a gift from the Duke of York, which he rarely wore) gleaming on his left hand.

“Nathan!” said Roth, startled. Meyer rarely breakfasted before nine these days. “This is certainly an unexpected pleasure. I had not thought to see you until this evening.”

“I have an appointment.” The dark head was bent over the coffee cup, eyes half-closed.

Roth wasn't deceived. His brother-in-law was at his most dangerous when he looked sleepy. “Whitehall ?” he queried, hoping the government was not going to frustrate his plans at the last minute. “More trouble in Austria?” In theory Nathan's service as an unofficial intelligence courier for Wellington was over. But as Roth himself had pointed out to his fellow bankers only a few days earlier, peace was sometimes as dangerous and unpredictable as war, and Meyer had already been to Vienna twice to “assist” the British delegation at the Congress.

“No, nothing of any importance,” said Meyer, still gazing into the unfathomable surface of his coffee. “A courtesy call.” His tone was pleasant, but discouraged further prying.

Roth narrowed his eyes and considered this response for a moment. Then, apparently changing the subject, he said, “Did you by any chance have time to consider the matter we discussed last night?”

“Good morning, Louisa,” said his brother-in-law courteously, rising and turning as Roth's wife entered behind him.

“How do you

do

that?” Louisa Roth waved him back to his chair with an irritated gesture. “I could have sworn I made no noise at all, and you were talking to Eli with your back to this door!”

do

that?” Louisa Roth waved him back to his chair with an irritated gesture. “I could have sworn I made no noise at all, and you were talking to Eli with your back to this door!”

“Your elegant perfume,” suggested Meyer, beginning to smile. “It preceded you into the room.”

“I do not wear perfume during the day, as you know very well.”

“The whisper of your silk skirts.”

“Wool,” she pointed out, spreading the soft maroon fabric out for inspection.

Still standing, he bowed. “On you, my dearest Louisa, it glows like the finest satin. Hence my misapprehension.”

“Your misapprehension,” she said tartly, “consists of the belief that you must be on the alert twenty-four hours a day, lest some French villain attack us here in the heart of London nearly a year after Napoleon abdicated.” Without pausing to acknowledge Meyer's wry grimace, she turned to her husband. “And what, pray, were the two of you discussing last night?”

“I beg your pardon?” hedged Roth.

“I saw you giving Nathan those little glances after dinner,” she said, folding her arms. “The I-must-speak-with-you-alone glances. I therefore obligingly retired early. But now I see Rodrigo is upstairs counting Nathan's clean shirts, a postboy has just left a message in the kitchen about a vehicle for Wednesday morning, Nathan is at breakfast two hours earlier than usual, and you are interrogating him about some mysterious proposal. I assume all these events are connected.”

Roth brightened at the mention of the postboy. “You'll do it, then?” he asked, turning to Meyer.

“I don't see why not.” Meyer picked up his cup and drained it. “It will be a bit dull, I expect, but traveling in France under my own name still has the charm of novelty. I'll come round to the bank this afternoon and you can give me the particulars. For now though, I must beg both of you to excuse me. My appointment is in less than an hour, and the gentleman who awaits me is greatly enamored of the virtue of punctuality.” He bowed slightly and vanished.

Louisa Roth stared at the now-empty doorway. “Where is he going?”

“Whitehall, I would guess,” said Roth slowly, putting all the pieces together. That was not what she had meant, of course.

His answer did serve to distract her for a moment. “He denied itâI heard you ask him.”

“He was lying.” Recollecting his brother-in-law's precise words, he amended this statement. “Or rather, speaking disingenuously. I suspect the courtesy call is on Colonel Tredwell at the Horse Guards.” He stepped over to the table and pulled out a chair. “Some coffee, my dear?”

“No, thank you.” Distractions rarely worked on Louisa Roth for more than a minute. She moved to face him, and since he was rather short, her piercing blue eyes looked straight into his. “When I asked that question, I meant where was he going on Wednesday. France, it seems.”

“A quick trip. Nothing dangerous, no intrigues or burglaries, I promise you. I got word from a friend that a kinswoman of his was stranded south of Grenoble without a suitable escort. I thought Nathan could use a bit of mountain air, a change of scene.”

He could see from her expression that she no more believed his story than Nathan had last night.

“Eli, you are matchmaking again,” she said flatly.

“Nonsense.”

She sighed. “Nathan can fool me when he lies. You, however, cannot.”

“Well, what if I am matchmaking, as you call it?” he asked, exasperated. “You are just as eager as I am to see him remarry.”

“No, I am not. Eli, I believe this has become something of an obsession with you. I know that having Nathan in residence here, still unmarried after so long, is a daily reminder of his lossâand yours. But he has proposed moving out several times since the war ended, and perhaps you should agree the next time he does so. It might help you to remember that he is a grown man, that you are not responsible for his happiness.”

“I do not believe I am responsible for Nathan.” He scowled at his wife. “And I thought you enjoyed having him lodge here with us.”

“I do,” said Louisa, unruffled. “What female would not?”

It said a good deal for his relationship with his wife that he had never had a single qualm about housing his brother-in-law, even after Nathan's children had left the house. Eli was short, round, balding, and nearsighted. Nathan was tall, slim, dark-haired, and possessed of a commanding pair of nearly black eyes.

“But,”

she continued, “pleasant as I find Nathan's company, I will have to dispense with it if every time you see him you feel an overwhelming urge to drag him under a wedding canopy.”

she continued, “pleasant as I find Nathan's company, I will have to dispense with it if every time you see him you feel an overwhelming urge to drag him under a wedding canopy.”

“Louisa, my sister died more than fourteen years ago. It was understandable that he should grieve for a bit, but his refusal to consider taking another wife after so long is absurd, especially since he and Miriam were wed so young that he is still at an age when some men are marrying for the first time. I admit that our attempts to find him a bride have miscarried a few timesâ”

“More than a few,” muttered his wife.

“The situation is different now.” Roth gestured at the newspaper lying neatly folded and unread by Meyer's abandoned cup. “While the war was on, he distracted himself with his work for the army, with disguises and ciphers and forgeries and midnight landings on hidden beaches. But now the war is over. He no longer even has a father's responsibilities to occupy him; Rachel and James are settled in households of their own. He is bored and restless, ready for a change. I could see it in his eyes last night when I proposed this little jaunt to him. And observe: he has already agreed to go. He did not even take a day to think it over.”

She still looked skeptical. “Who is this friend of the family he is supposedly rescuing in the mountains of France?”

“A very suitable prospect,” he assured her. “A cousin of Joshua Hart, well educated, eager to travel, said to resemble her mother, who was a great beauty. Of course, I did not tell him that Miss Hart was an eligible young woman. I believe I gave him the impression that she was a bit of an invalid, taking the waters at Digne-les-Bains for her health.”

“He'll see right through your little plot the moment he meets her.”

“I think not.” Roth gave a satisfied smile. “This is one of my better schemes. After all, even Nathan is not omniscient.”

“Oh?” said his wife. “Then how is it that between ten last night and seven this morning he has recalled his most trusted servant from Kent, arranged for a post chaise, and scheduled an appointment at Whitehall, where he will no doubt offer to carry confidential messages to France? Or are you going to pretend that he knew nothing of this request of yours until nine hours ago? That Rodrigo's return and Nathan's meeting with the colonel are happy coincidences?”

Roth drew himself up magisterially. “I will not deny that Nathan is uncannily observant. Clearly he got wind of this somehow last week, when I first received Hart's letter. But anticipating a voyage to France on the strength of gossip at our bank is not the same as anticipating what will happen when he gets there.”

“I know what will happen,” she retorted. “He will be his usual courteous, impenetrable self, he will escort Miss Hart back to England as quickly as possible, and then he will stalk in here and raise his eyebrows at you just as he did after your other attempts. If I am lucky, the disappointed bride-to-be will not fall desperately in love with him, as two of the others did, and I will not have to spend months avoiding her and all her relatives.”

“We shall see,” said Roth, turning back to the sideboard. “I am two moves ahead of him this time, my dear. And matchmaking is not a game familiar to Nathan.”

She frowned at him. “You are keeping something from me.”

He did not respond, but picked up the coffee pot.

“Are you afraid I will tell Nathan?”

“No,” he said, pouring her a cup and setting it at her place. “I am afraid you will say âI told you so' if it doesn't work.”

Not for nothing was Louisa Roth the wife of a financier. “What are the chances of success, in your estimation?”

“Something like one in ten.”

“Well,” she said, settling into her chair, “for an affair involving Nathan and a marriageable female, those are quite respectable odds.”

Other books

Fall Into Me by Linda Winfree

Not First Love by Lawrence, Jennifer

Kismet by Cassie Decker

Claimed by the Grizzly by Lacey Thorn

Hooked #2 (The Hooked Romance Series - Book 2) by Adams, Claire

Hemingway's Ghost by Green, Layton

Hidden Pleasures by Brenda Jackson

Stepbrother: Impossible Love by Victoria Villeneuve

Trepidation by Chrissy Peebles