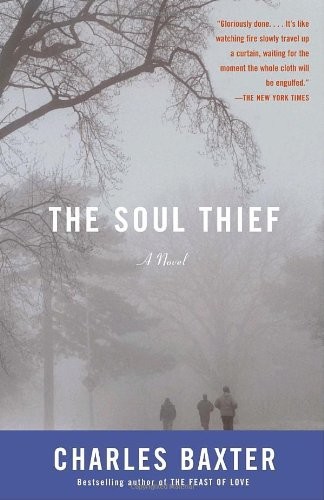

The Soul Thief

ALSO BY CHARLES BAXTER

f i c t i o n

Saul and Patsy

The Feast of Love

Believers

Shadow Play

A Relative Stranger

First Light

Through the Safety Net

Harmony of the World

p oe t ry

Imaginary Paintings

e s s ay s

Beyond Plot

Burning Down the House

The Soul Thief

This book has been optimized for viewing at a monitor setting of 1024 x 768 pixels.

The

Soul

Thief

charles b axter

pa n t h e o n b o o k s n e w yo r k This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2008 by Charles Baxter

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: George Braziller, Inc.: Excerpt from “Golden State” from

Golden State

by Frank Bidart (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1973).

Reprinted by permission of George Braziller, Inc.

Oxford University Press: Excerpt from “The Census-Takers”

from

Selected Poems

by Conrad Aiken (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Baxter, Charles, [date]

The soul thief / Charles Baxter.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37709-8

1. Graduate students—Fiction. 2. Buffalo (N.Y.)—Fiction.

I. Title.

ps3552.a854s68 2007

813'.54—dc22

2007018119

v1.0

For Michael Scrivener and Mary Ann Simmons

and for Ross Pudaloff

I dreamed I

had

my wish:

—I seemed to see

the conditions of my life, upon

a luminous stage: how I could change,

how I could not: the root of necessity, and choice.

— f r a n k b i da r t, “ g o l de n s tat e ”

1

He was insufferable, one of those boy geniuses, all nerve and brain.

Before I encountered him in person, I heard the stories.

They told me he was aberrant (“abnormal” is too plain an adjective to apply to him), a whiz-kid sage with a wide range of affectations. He was given to public performative thinking. When his college friends lounged in the rathskeller, drinking coffee and debating Nietzsche, he sipped tea through a sugar cube and undermined their arguments with quotations from Fichte. The quotations were not to be found, however, in the volumes where he said they were.

They were not anywhere.

He performed intellectual surgery using hairsplitting distinctions. At the age of nineteen, during spring break, he took up strolling through Prospect Park with a walking stick and a fedora. Even the pigeons stared at him. Not for him the beaches in Florida, or nudity in its physical form, or the vulgarity of joy. He did not often change clothes, preferring to wear the same shirt until it had become ostentatiously threadbare. He carried around the old-fashioned odor of 4

c h a r l e s b a x t e r

bohemia. He was homely. His teachers feared him. Sometimes, while thinking, he appeared to daven like an Ortho-dox Jew.

He was an adept in both classical and popular cultures.

For example, he had argued that after the shower scene in Hitchcock’s

Psycho,

Marion Crane isn’t dead, but she isn’t not-dead either, because the iris in her eyeball is constricted in that gigantic close-up matching the close-up of the shower drain. The irises of the dead are dilated. Hers are not. So, in some sense, she’s still alive, though the blood is pouring out of her wounds.

When Norman Bates carries Marion Crane’s body, wrapped in a shower curtain, to deposit in the trunk of her car for disposal, they cross the threshold together like a newly married couple, but in a backwards form, in reverse, a psychotic transvestite (as cross-dressers were then called) and a murdered woman leaving the room, having consummated something. The boy genius wouldn’t stop to explain what a backwards-form marriage might consist of with such a couple, what its shared mortal occasion might have been.

With him, you had to consider such categories carefully and conjure them up for yourself, alone, later, lying in bed, sleepless.

Here I have to perform a tricky maneuver, because I am implicated in everything that happened. The maneuver’s logic may become clear before my story is over. I must turn myself into a “he” and give myself a bland Anglo-Saxon Protestant name. Any one of them will do as long as the name recedes into a kind of anonymity. The surname that I will therefore give myself is “Mason.” An equally inconspicuous given name is also required. Here it is: “Nathaniel.” So that is who I am: Nathaniel Mason. He once said that the name “Nathaniel” was cursed, as “Ahab” and “Judas” and t h e s ou l t h i e f

5

“Lee Harvey” were cursed, and that my imagination had been poisoned at its source by what people called me. “Or else it could be, you know, that your imagination heaves about like a broken algorithm,” he said, “and

that

wouldn’t be so bad, if you could find another algorithm at the horizon of your, um, limitations.”

He himself was Jerome Coolberg. A preposterous moni-ker, nonfictional, uninvented by him, an old man’s name, someone who totters through Prospect Park stabilized with a cane. No one ever called him “Jerry.” It was always “Jerome”

or “Coolberg.” He insisted on both for visibility and because as names they were as dowdy as a soiled woolen overcoat.

Still, like the coat, the name seemed borrowed from somewhere. All his appearances had an illusionary but powerful electrical charge. But the electricity was static electricity and went nowhere, though it could maim and injure. By “illusionary” I mean to say that he was a thief. And what he tried to do was to steal souls, including mine. He appeared to have no identity of his own. From this wound, he bled to death, like Marion Crane, although for him death was not fatal.

2

On a cool autumn night in Buffalo, New York, the rain has diminished to a mere streetlight-hallucinating drizzle, and Nathaniel Mason has taken off his sandals and carries them in one hand, the other hand holding a six-pack of Iroquois Beer sheltered against his stomach like a marsu-pial’s pouch. He advances across an anonymous park toward a party whose address was given to him over the phone an hour ago by genially drunk would-be scholars. On Richmond? Somewhere near Richmond. Or Chenango. These young people his own age, graduate students like himself, have gathered to drink and to socialize in one of this neighborhood’s gigantic old houses now subdivided into apart-ments. It is the early 1970s, days of ecstatic bitterness and joyfully articulated rage, along with fear, which is unarticulated.

Life Against Death

stands upright on every bookshelf.

The spokes of the impossibly laid-out streets defy logic.

Maps are no help. Nathaniel is lost, being new to the baroque brokenness of this city. He holds the address of the apartment on a sopping piece of paper in his right hand, the hand that is also holding the beer, as he tries to read the directions t h e s ou l t h i e f

7

and the street names. The building (or house—he doesn’t know which it is) he searches for is somewhere near Klein-hans Music Hall—north or south, the directions being con-tradictory. His long hair falls over his eyes as he peers down at the nonsensical address.

The city, as a local wit has said, gives off the phosphores-cence of decay. Buffalo runs on spare parts. Zoning is a joke; residential housing finds itself next to machine shops and factories for windshield wipers, and, given even the mildest wind, the mephitic air smells of burnt wiring and sweat.

Rubbish piles up in plain view. What is apparent everywhere here is the noble shabbiness of industrial decline. The old apartment buildings huddle against one another, their bricks collapsing together companionably. Nathaniel, walking barefoot through the tiny park as he clutches his beer, his sandals, and the address, imagines a city of this sort abandoned by the common folk and taken over by radicals and students and intellectuals like himself—Melvillians, Hawthornians, Shakespeareans, young Hegelians—all of whom understand the mysteries and metaphors of finality, the poetry of last-ness, ultimaticity—the architecture here is unusually

fin de

something, though not

siècle,

certainly not that—who are capable, these youths, of turning ruination inside out. Their young minds, subtly productive, might convert anything, including this city, into brilliance. The poison turns as if by magic into the antidote. From the resources of imagination, decline, and night, they will build a new economy, these youths, never before seen.

The criminal naïveté of these ideas amuses him. Why not be criminally naïve? Ambition

requires

hubris. So does ideal-ism. Why not live in a state of historical contradiction?

What possible harm can there be in such intellectual narcissism, in the Faustian overreaching of radical reform?

8

c h a r l e s b a x t e r

Even the upstate New York place-names seem designed for transformative pathos and comedy: “Parkside” where there is no real park, streets and cemeteries in honor of the thirteenth president, Millard Fillmore, best known for having introduced the flush toilet into the White House, and . . . ah, here is a young woman, dressed as he himself is, in jeans and t-shirt, though she is also wearing an Army sur-plus flak jacket, which fits her rather well and is accessorized with Soviet medals probably picked up from a European student black market. Near the curb, she holds her hand to her forehead as she checks the street addresses. She is, fortunately, also lost, and gorgeous in an intellectual manner, with delicate features and piercing eyes. Her brown hair is held back in a sort of Ph.D. ponytail.

They introduce themselves. They are both graduate students, both looking for the same mal-addressed party, a party in hiding. In homage to his gesture, she takes off her footwear and puts her arm in his. This is the epoch of bare feet in public life; it is also the epoch of instantaneous bond-ings. Nathaniel quickly reminds her—her name is Theresa, which she pronounces

Teraysa,

as if she were French, or otherwise foreign—that they have met before here in Buffalo, at a political meeting whose agenda had to do with resistance to the draft and the war. But with her flashing eyes, she has no interest in his drabby small talk, and she playfully mocks his Midwestern accent, particularly the nasalized vowels. This is an odd strategy, because her Midwestern accent is as broad and flat as his own. She presents herself with enthusiasm; she has made her banality exotic.

She has met everyone; she knows everyone. Her anarchy is perfectly balanced with her hyperacuity about tone and tim-bre and atmosphere and drift. With her, the time of day is t h e s ou l t h i e f

9

either high noon or midnight. But right now, she simply wants to find the locale of this damn party.

Again the rain starts.

Nathaniel and Theresa pass a park bench. “Let’s sit down here for a sec,” she says, pointing. She grins. Maybe she doesn’t want to find the party after all. “Let’s sit down in the rain. We’ll get soaked. You’ll be the Yin and I’ll be . . .

the other one. The Yang.” She points her index finger at him, assigning him a role.

“What? Why?” Nathaniel has no idea what she is talking about.

“

Why?

Because it’s so Gene Kelly, that’s why. Because it’s not done. No

sensible

person sits down in the rain.” She salts the word “sensible” with cheerful derision. “It’s not, I don’t know,

wise.

There’s the possibility of viral pneumonia, right?

You’d have to be a character in a Hollywood musical to sit down in the rain. Anyway, we’ll arrive at the party soaking wet. Our clothes will be attached to our skin, and we’ll be

visible.

” She seems to inflect all her adjectives unnecessarily.

Also, she has a habit of laughing subvocally after every other sentence, as if she were monitoring her own conversation and found herself wickedly amusing. Together they do as she suggests, and she takes his hand in a moment of what seems to be spontaneous fellow feeling. “I can stand a little rain,”

she says quietly, fingering his fingers, quoting from somewhere. She leans back on the park bench to let the droplets fall into her eyes. To see her is heaven, Nathaniel thinks. No wonder she wears a flak jacket. They wait there. A minute passes. “Boompadoop-boom ba da boompadoopboom,” she sings, Comden-and-Greenishly.